This is part 3, the conclusion of our interview with Dr. Sho Konishi of Oxford on his stunning work for Harvard University Press – Anarchist Modernity: Cooperatism and Japanese-Russian Intellectual Relations in Modern Japan.

Dr. Konishi’s scholarship has profoundly influenced how I think about Capitalism, the State, Activism and building a progressive future. You can read part 1 and part 2 here.

Asia Art Tours: You explicitly highlight the role of translation in creating an environment of cooperative Anarchism between Russia and Japan:

Rather than a form of unequal power relations, translation in this discourse was a transnational exchange conducted on equal grounds that implied a non-hierarchical world order beyond the epistemological limits of East-West relations.

Could you discuss how you see translation as critical to understanding the Cooperatist Anarchism of the period? How were works that were forbidden or beyond criticism in one country (Tolstoy, The Tao te Ching) exchanged between countries in a way that created radical new meanings and solidarity between Russian and Japanese anarchists

SHO KONISHI: Translation is one of the most productive ways to understand the intellectual history of Japan. The intellectual history of modern Japan is actually a history of translation in one form or another. If intellectual history is a history of translation, then all modern intellectual histories are in a way, transnational histories.

There are a number of theories out there about translation in intellectual history. One theory is that translation is an expression and producer of cultural nationalism as identity and difference. This is because translation acts to allow the reader to identify his or her ‘mother’ language from foreign language as the ‘other.’ In modern Japan, this was predominantly occurring in translations of English, which, according to Naoki Sakai, produced a sense of the other vs. the self, West vs. Japan. Another theory is of translation as self-colonization, according to which translations of English literature were an act of self-colonization, of adaptation to and a perceived superior culture and adoption of the Western concept of ‘self’. In contrast, the translation practices that I talk about in my book uprooted such dichotomies. They negated colonization practices justified by ideologies of civilizational hierarchy. The translations of Tolstoi and Tao te Ching liberated their readers from that hierarchy and its embedded temporality. They allowed ordinary people to be the vehicles of social progress. These translations were not expressions of cultural nationalism or self-colonization, but rather a practice of liberation that embraced a global outlook.

(The Tao te Ching had a profound impact on the anarchists of Japan and Russia. Famed writer and anarchist Ursula K Le Guin was also deeply influenced by this classic text)

This history of translation allows us to better understand how translation can be an even more innovative practice and process than we thought. Not only were they not translating Western terms, but their translations uprooted the very Western terms and the meanings embedded in them. In this way, they liberated people from the constraints of the Western meaning of modern religion.

In order to be civilized, human beings no longer needed to be Christian or Muslim, but just oneself, as unique individuals. In plural, they were called ‘heimin’ (‘the common people’). This conflicted with the standardized usage of the term for ‘the people’ as Kokumin (‘the nation’s subjects’).

Tolstoi was the most translated writer in the entire history of translation practice in Japan. He was translated as a religious figure, when religion was critical to determine not only who was to carry civilization, but what sort of idea of progress. Konishi’s introduction and translation of Tolstoian religion changed the temporality of modernity in Japan and people’s belonging to that temporality. It allowed one to have a much broader sociality beyond the nation state. It allowed and nurtured non-state level transnational links with other Asian countries outside the relationality of colonizer and colonized, White and Yellow, and civilized and uncivilized. The translations allowed for new temporalities that liberated people from the constraints and limits of Western modernity that had generated such conceptual hierarchy of divisions for world order. An alternative world order was simultaneously taking root that changes the way we think about the global history today at large.

AAT: During the Russo-Japanese War, How did State institutions and media promote its concept of Kokumin and how did this contrast and compete with Non War and Cooperatist Anarchists who promoted the concept of the Heimin? (I found your writing about the battle to define the meanings of “honor” and “peace” to be fascinating) What was at stake in this battle of meanings?

SK: In the Russo-Japanese War, war was peace in a way, a ‘peace’ that revolved around the territorial notion of the imperial nation state, the territorial utopia. To win war meant to gain peace and to adhere to an idea of progress toward a perfected space governed by civilized human beings, u-topos. The Nonwar Movement at the time was not reducible to anti-imperialism. Their critique was not only anti-war, but against that war and its idea of peace that the war was intended to bring.

Interiority became a site of contestation. Teddy Roosevelt promoted the idea that anarchism was terrorism, while Nonwar adherents saw ‘terror’ as belonging to the state’s uncontrolled abuse of power. Nonwar adherents had no intention of using violence. Meanwhile, the state used violence as means to control and govern the state’s subjects. Kotoku Shusui, a leading anarchist and the leading voice of the Nonwar Movement, and 11 other alleged co-conspirators including Kotoku’s common-law wife, were murdered by the state for conspiring to assassinate the emperor in 1910. Osugi Sakae, translator of accounts of the dung beetle, was also murdered, by the military police, 10 years later.

The determination of what was natural was at stake. All other moral vocabularies followed to that end. For cooperatist anarchists, what was natural was symbiotic nature. Around the time of the war, people were reading not books about war, protest or revolution, but the above-mentioned Ilya Mechnikov’s writings on microbiology in which he described symbiosis functioning on the micro-most level within the human body. A battle of meanings over ‘nature’ was part of a larger battle over the definition of what was good.

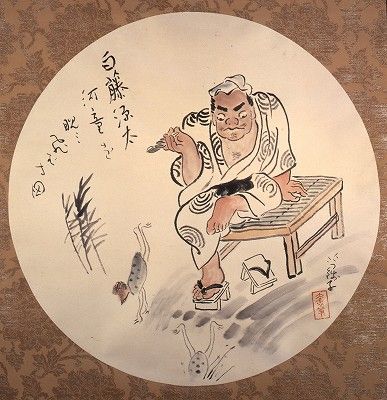

(a later period Ogawa Usen Cartoon)

If we look at the artist Ogawa Usen’s cartoons in Nonwar publications during the war, we find women, older men, and fishermen quietly napping, sleeping and at rest. These were far from the action-oriented images we might expect to find in a time of war. The images of napping during a time of war were very powerful. In the middle of the day, when one ought to have been most productive, an older man was depicted fishing – not just fishing, but napping quietly and alone while he waits. The cartoon shows him sleeping in the afternoon sun while a fish tugs at his line. This, at the height of war, was one of numerous powerful cartoons with hidden critical commentaries by Ogawa, published in the leading Nonwar publication of the time, Heimin shimbun. His perspective, aligned with the philosophy of the Tao te ching and perhaps easily lost on us today, would have been picked up by readers at the time in Japan. Readers would have been widely familiar with the Tao te ching, a key text at the time. This classical Chinese philosophy usurped the concentration of power in the hands of rulers and elites through its focus on the divine power and majesty of the small and weak masses, in gentle and peaceful inaction or natural action, as opposed to the force and power of rulers and elites. It saw the divine itself as flowing within the small and weak.

Over the past two decades of our own time, we’ve been facing a similar battle of definitions, based on which a different word order might be imagined. Many examples come to mind. An obvious one, for instance, is the term, ‘globalization,’ the spread and institutionalization of capitalist modernity worldwide. The related term ‘global history’ that reflects ‘globalization’ has the power to justify the present and thereby close the future, rather than opening it up to alternative possibilities. What sort of ‘global history’ would we see if we were to take anarchist modernity seriously?

AAT:During the War, you provide insight about Japan’s POW Camps as sites of revolutionary potential:

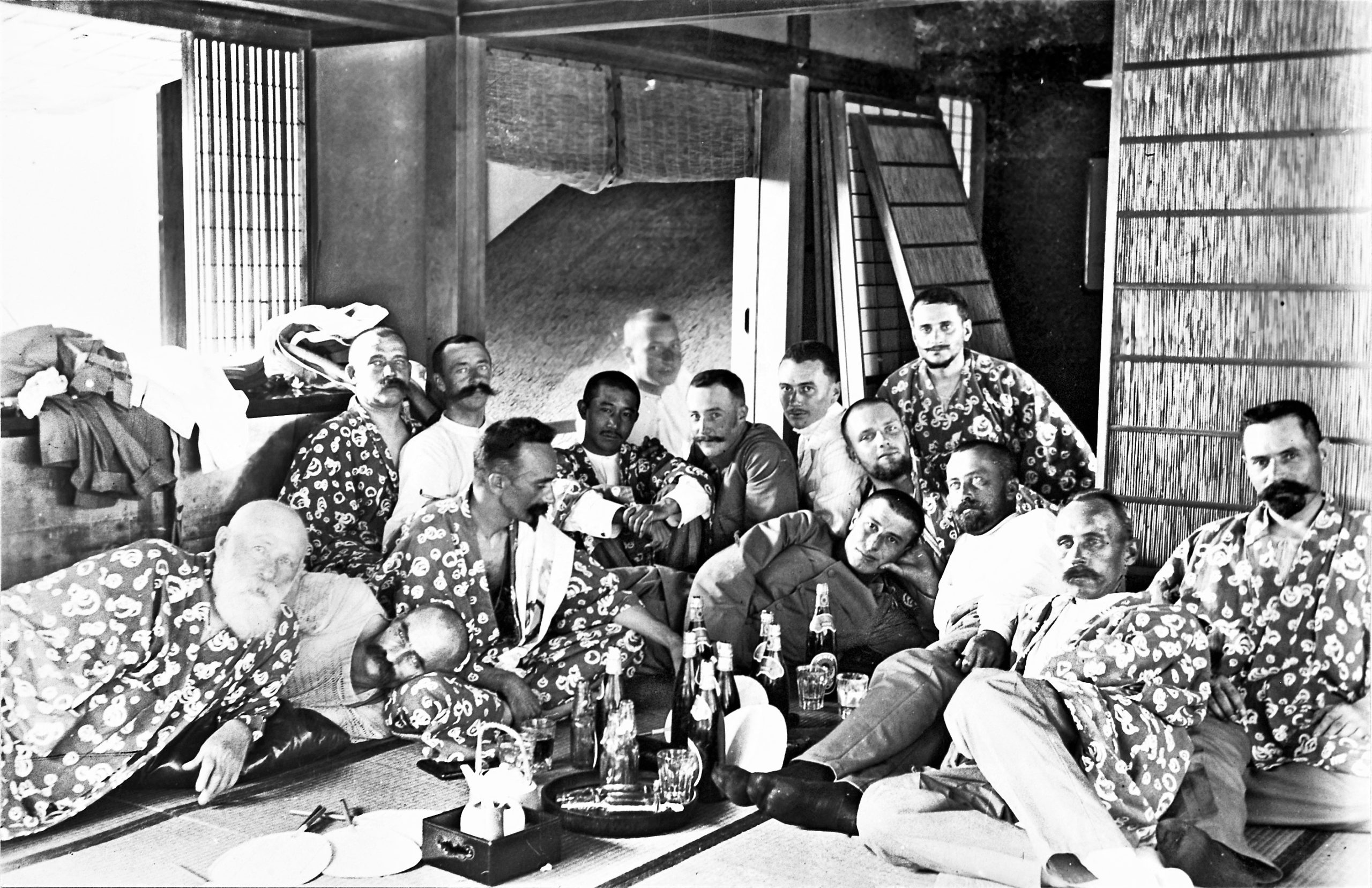

With some ninety thousand Russian POWs scattered in twenty- eight POW camps across Japan, the camps served as ideal hubs… for the networked activities of Non-war Movement activists and their Russian revolutionary counterparts… These figures turned the camps into a kind of a liberal arts college, or a “barbed-wire college”.. . Without charge for tuition and with free room and board, Japanese socialists and anarchists, as well as Russian revolutionaries in Japan, treated the camps as ideal campuses to educate captured Russian soldiers . . . Hundreds of thousands of Russian soldiers were radicalized by their experiences in the war and their education in the POW camps.

Could you describe how revolutionaries took advantage of these punitive spaces and transformed them into sites of revolutionary potential? Are there contemporary lessons which can be taken and applied to the modern panopticon of prisons and camps that currently festers across the globe?

SK: The tens of thousands of Russian POWs in Japanese camps during the Russo-Japanese War were already discontent. It was a matter of redirecting that energy and critical mind toward revolutionary thought and action. Russian Populist revolutionaries in Japan led by the physician Nikolai Sudzilovskii-Russel published a newspaper, Iaponiia i Rossiia (‘Japan and Russia’), which was disseminated to the POWs. Russel was given free hand to disseminate his material. I believe the Japanese government was well aware of the revolutionary nature of the material, as it had been using secret agents to support and funnel money to Russian revolutionaries in an attempt to destabilize the Russian government. Some of the biggest names in the Russian revolutionary movement moved through Japan in this period, and there were powerful effects of the education and coaching of POWs in garnering the POWs’ support for the Russian revolutionary movement. Indeed, the Russian writer Andrei Belyi depicted the return to Russia of mass waves of revolutionary minded veterans of the Russo-Japanese War in his 1913 novel Petersburg.

(Russian POWs from the Russo-Japanese War. The camps became a source of collaboration and recruitment for Japan’s anarchists, communists and sympathetic Russian prisoners tired of war. Source: http://polithistory.ru/en/visit_us/view.php?id=13511)

Time was suspended in the camps, and there was quite a lot of time to kill. Being in the camps gave people time to reflect. The war was brutal, and people wondered for what they had fought. The Russian POWs felt the contrast between the brutality of the war being fought against Japan, and the incredible suspended period of calm in the camps, when they were free to walk around the town, interacting freely with Japanese people. They were treated incredibly well in Japan, and given access to the highest standards of medical care. This was in accordance with the Japanese government’s effort to show the high civilizational achievement. The same motive that led Japan to win the war with Russia, led it to treat Russian POWs extremely well.

In the POWs’ psyche, their service to the state was pending. Japanese treated the POWs generously as general civilians, and the POWs no longer perceived themselves as soldiers serving the nation state with weapons. In the camps, the POWs transformed their thinking, from service to the nation state, to conceiving of themselves as people without the state, which they shared with the Japanese Nonwar Movement.

AAT: The final pairing I’d like to highlight is Anarchist Ōsugi Sakae and Jean-Henri Fabre the French Entomologist.

Could you discuss how Japan’s anarchists saw their own perspectives within Fabre’s writing on the natural world? Why did this viewpoint resonate so vividly with the wider Japanese populace (to this day). Lastly, why did they reject the more Malthusian and Spencerian notions of brutal competition and hierarchy expressed by Darwin.

(The Entomologist Jean-Henri Fabre, whose stories of insects cooperating and working together remain wildly popular in present-day Japan. Fabre’s works were originally translated by Japanese Anarchists, who gravitated towards his presentation of nature and cooperation, as opposed to the brutal competition emphasized by capitalists and Darwin)

SK: From the outset, Fabre and Osugi had different ideas about the natural world. While Fabre saw insects as God’s creation, Osugi saw them as cooperatively connected with the wider nature including humankind, kind of like the idea of ‘Gaia’ as James Lovelock and Lynn Margulis have called it.

Osugi’s originality in his translations made Fabre’s writings on insects extremely popular in Japan. The way Osugi translated Fabre was vivid, colloquial, humanizing and humorous. Many translations have appeared since then, but I still think it’s hard to beat the first by Osugi.

His translations appeared within a broader interest among cooperatist anarchists in the natural sciences, most specifically, a fascination with the smallest creatures of our universe. Interestingly, while Lev Mechnikov’s writings never became known in Japan, it was Lev’s younger brother Ilya, a Nobel Prize-winning microbiologist, whose writings came to be widely read among cooperatist anarchists. Ilya Mechnikov’s writings on microbiology proved that human beings’ innermost being was mutual aidist. He demonstrated that the nature that surrounds us and is within us from our very cells is symbiotic. Thus, symbiotic development was at the heart of our evolutionary origins. Many decades after Mechnikov’s own work, the world-renowned biologist Margulis developed her own work, inspired by the symbiotic functioning of phagocytosis by Mechnikov and other early twentieth-century Russian and Soviet biologists. She took important cues from these Russian biologists on the role of symbiogenesis in evolution, biologists who likely worked in the same circles as Ilya Mechnikov.

Why did it resonate with the wider Japanese populace? It perhaps echoed their mode of existence and sociality, particularly at that time. Anthropologists often make sweeping generalizations and assumptions that divide so-called individualist societies vs. collectivist ones, as if human subjectivities and societies can be divided into two models. Cooperatist anarchists reflected symbiotic human subjectivity onto the tiniest, seemingly most unimportant little creatures, like microbes and dung beetles. They demonstrated these little creatures doing, and their acts as being not only necessary for the health of larger society and environment, but also illuminating for our understanding of the nature of our own existence. Each tiny element, each little creature, was viewed as significant for the well-being of the larger entity that we are all a part of. It was both aesthetic and ethical. It was also simultaneously collective and individual. To be individual, one needs to be collective, and to be collective, one must be individualistic. So, neither of these terms would have captured their subjectivity.

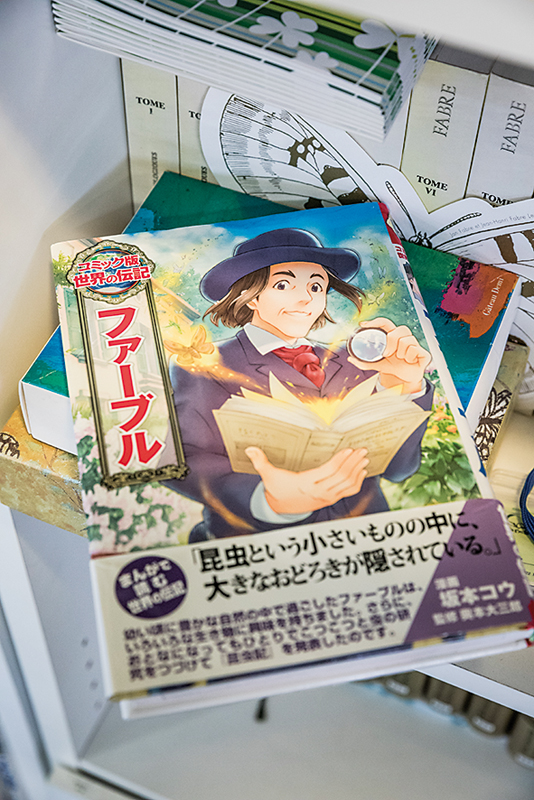

(Jean-Henri Fabre in Manga form! His works have been made into numerous cartoons and comics in Japan. )

Cooperatist anarchists did not reject Darwin’s On the Origin of Species, but they did reject The Descent of Man, by ignoring it. Darwin’s understanding of evolution was embraced as it suited their idea that everything is constantly evolving, and forming and reforming. Competition as well as cooperation was essential to the survival of any species. With each individual talent gifted by Gxd, each has different roles to play, resulting in an intricate interconnectivity of energies. For cooperatist anarchists, the world of insects was a missing piece in their worldview. If colonizers at the time sought to prove the right of their mission by measuring the bones and skulls of inferior creatures in accordance with the Western civilizational model of the hierarchy of species, Japanese anarchists sought to prove their worldview by removing the hierarchy of world order. They did so by decentering the world, talking about the dung beetle and microbes, and exploring the negative discovery of the universe. Fabre fit their concept of the natural world that embraced the smallest and seemingly most useless creatures like the dung beetle, and made it the hero and subject of fascination, recounting in smallest detail its utterly eccentric behavior. Yet this odd eccentricism made the dung beetle the most essential creature for the survival of human civilization. Its recycling of animal dung allowed for the survival of the entire agricultural world that is so essential to human survival. This is perhaps why the scarab beetle, a type of dung beetle, was worshiped by the Egyptians. The notion accords well with the earlier mentioned philosophy of Tao te Ching. Ever since Osugi’s translation, the beetle has been called endearingly the ‘dung ball roller’ by Japanese children and adults alike, and spawned a mass culture of dung beetle paraphernalia, from t-shirts to model figures, etc. Its mass popularity can be entirely attributed to Japanese anarchist translations of Fabre’s scientific observations of the dung beetle’s and other insect behaviour. Their translations have ever since the early twentieth century been the Mother Goose of Japan, the book that every Japanese child reads. Children’s collection and observations of the behavior of beetles in nature have been ingrained in the play repertoire of Japanese children and primary school education ever since.

Why did the wider Japanese populace reject Spencerian Darwinism’s competition? They faced the brutality of capitalism, money-driven social norms and ethics that were antithetical to more rooted anarchist notions of symbiotic coexistence and progress driven by mutual aid. They were attracted not to ideas of segregation or hierarchy, but rather to anarchist celebrations of the ‘weak’ (as defined by Western modernity) as the strong, the necessary, and the divine. This helped lead to the widespread interest in Esperanto, again from below. Esperanto was a language without culture that simultaneously embraced all languages and cultures equally — at a time when culture meant race, and race meant the hierarchy of civilization, which served as an ethical justification for the weak to be colonized and controlled under eugenicist policies.

AAT: To conclude with the beginning, early in the book you bring up Zygmunt Bauman’s criticism of the “Sedentary Imagination” of Western Modernity, which you explain (through his framing) as one tied to boundaries, borders, a sovereign with power and legal order. This is compared throughout your book to the bottom-up and borderless utopia of everyday practice that inspired so many Japanese and Russian Anarchists.

As Western Modernity is crumbling and Capitalism threatens to extinguish all life on Earth do you see a chance for the politics and international collaboration that we see in your book to resurface? If so, what inspiration or tactics can contemporary activists find in the image of the Heimin and Cooperatist Anarchists of your book?

SK: Yes, I do.

What inspiration? That’s not for me to say. I’m a mere student of history. If 10 people read it, there will be more than 10 ways to reflect the ideas found in the book. But I imagine that what you are doing here will certainly be an inspiration that contemporary folks would find important. And as such, let me thank you again for such an exceptional opportunity to communicate with you in this way.

For Dr. Konishi’s incredible scholarship, please see his book Anarchist Modernity: Cooperatism and Japanese-Russian Intellectual Relations in Modern Japan by Harvard University Press.