We’re delighted to bring you the conclusion of our interview with the Chuang Collective. They produce some of the most useful and radical scholarship on China, Communism, Labor, & Organizing. We discuss The Nation State, Protests, Riots and building actual solidarity with China.

(Read Part 1 here)

Asia Art Tours: With the increasing of borders, surveillance, state violence and ethosupremacy both within China and globally. I wanted to ask how stable you see China as a functional nation-state for the foreseeable future? And has increasingly brutal governance/ethnosupremacy globally influenced CHUANG’S conclusions about the desire for nation-states in a communist/anarchist future?

Chuang(闯):Context is important here. When you say “increasingly brutal governance/ethnosupremacy,” we would ask: relative to where and when? In reality, it seems that things which have always been happening are just recently being made visible to many people. This is what you could maybe call the “Trump phenomenon” in the US, for example, where suddenly mass incarceration, forced labor, the construction of concentration camps for migrants, family separation at the border, rampant police murder, far-right assassinations and mass shootings—all these things suddenly appear to a bunch of people all at once not because they didn’t exist before but instead because the election of Trump turned such peoples’ eyes toward political topics for the first time in their lives. The reality, of course, is that everything listed above has a long, long history in America. In fact, that list is a fairly good summary of American history in general!

We think that any politics build around “pressuring” states or corporations to act better is going to be a losing game. Think, for example, of the giant global protests nearly two decades ago when the US invaded Iraq. There were enormous demonstrations in countries across the world. All kinds of diplomatic pressure emerged, many nations refused to join the US-led effort, anti-war groups sprouted up across the US itself and organized continually as the war began and dragged on. And it did absolutely nothing.

We think that any politics build around “pressuring” states or corporations to act better is going to be a losing game. Think, for example, of the giant global protests nearly two decades ago when the US invaded Iraq. There were enormous demonstrations in countries across the world. All kinds of diplomatic pressure emerged, many nations refused to join the US-led effort, anti-war groups sprouted up across the US itself and organized continually as the war began and dragged on. And it did absolutely nothing.

So proper historical framing is actually very important. Is it true that, if you are a communist or an anarchist organizing for racial equality in the US, you might now have your communications surveilled? That you might be beaten by the police, thrown in prison, shot by far-right lunatics? Of course it is. But the same was true in the 1960s, the 1930s, the 1890s, etc. We could say that exact same thing for China, by the way, maybe tweaking the years a little. So in all these senses, we tend to exaggerate what, exactly, is new and what isn’t, because our immediate reference points are often a fairly recent history which had been filled with propaganda promoting the end of history as such, the end of class struggle, how the economy was growing, how everyone was middle class, all that nonsense. Of course even then it wasn’t true if you were paying attention to the whole world, but it’s this false veneer of recent history that usually acts as our spontaneous reference point in trying to understand this period in which that veneer is slipping away. This doesn’t mean that the state doesn’t necessarily have far more expansive powers today, it’s just important to measure exactly how it does and doesn’t. Obviously, the intricacy of surveillance is greater today than it was in the past, for instance. And the real issue here is basically whether or not these capacities make modern states more resilient to internal popular challenges against its power.

Certainly, we can point to the really extreme inequality when it comes to the ability to mobilize force and violence. Measured at a technical level, the contemporary capitalist class, organized into myriad states, is terrifying in its ability to, quite literally, destroy the world. At the same time, even the greatest military supremacy is clearly unable to easily deal with a popular, asymmetrical struggle against it. If you then add the classic revolutionary conditions into that equation—things like mutiny within the armed forces, for instance, mass defection from the conservative side to the revolutionary one, breakdown of the productive apparatus, etc.—it seems to hint that this imbalance might not be as severe as it looks at first glance. Revolutionary capacity can’t just be measured by counting guns. Instead it’s something intensive, it involves a real breakdown in the mainline circuits of the global economy and that does a very different kind of damage to the power of capitalist class than even many historic revolutions. So that’s one reason why the Chinese case is so interesting to us, because of the unique ways in which the global industrial system has concentrated a number of absolutely essential nodes within China, and what might happen if a local rebellion were to halt that production.

Finally, you ask about “the desire for nation-states in a communist/anarchist future.” The answer here is very simple: there is no such desire. No self-respecting communist can look you in the face and say that there is still a “state” in communism. If they do so, they aren’t a communist in any sense of the word. And of course the anarchists have no desire for a state. Meanwhile, the term “nation-state” has always been more of a propaganda effort than a description of any fundamental unity. If states have a linguistic or national/cultural character, it’s because they were at their founding and are still today the administrative mechanism of certain factions of capitalists (and historically of course landed elites, old aristocrats, etc.) who share a rough linguistic or cultural affinity and therefore began to coordinate their interests according to these accidents of history that had thrown them together. These were contingent alliances among capitalists, often inherited from pre-capitalist geographies, which then took on the character of more general “national” cultures.

When you say “increasingly brutal governance/ethnosupremacy,” we would ask: relative to where and when? In reality, it seems that things which have always been happening are just recently being made visible to many people. This is what you could maybe call the “Trump phenomenon” in the US, for example, where suddenly mass incarceration, forced labor, the construction of concentration camps for migrants, family separation at the border, rampant police murder, far-right assassinations and mass shootings—all these things suddenly appear to a bunch of people all at once not because they didn’t exist before but instead because the election of Trump turned such peoples’ eyes toward political topics for the first time in their lives.

When you say “increasingly brutal governance/ethnosupremacy,” we would ask: relative to where and when? In reality, it seems that things which have always been happening are just recently being made visible to many people. This is what you could maybe call the “Trump phenomenon” in the US, for example, where suddenly mass incarceration, forced labor, the construction of concentration camps for migrants, family separation at the border, rampant police murder, far-right assassinations and mass shootings—all these things suddenly appear to a bunch of people all at once not because they didn’t exist before but instead because the election of Trump turned such peoples’ eyes toward political topics for the first time in their lives.

But even the “nation” is often a joke, to be honest. Because the fact is that the most homogenous nations almost always have had to (often quite violently) enforce standardization and assimilation into that supposedly self-same national culture. If you look at the early-modern formation of these nation-states in Europe, for example, the historical documents are filled with attempts to force everyone to speak mutually-intelligible, standardized versions of, say, French, and to celebrate a particular subset of distinctly national cultural features. In many places, even ignoring the most egregious examples from settler-states, this meant a pretty substantial suppression of internal linguistic and cultural diversity (think, for example, of why people speak English in the British Isles, and not, say, Welsh). This is of course exactly what the Chinese state continues to pursue today, causing the recent conflict around Mongolian language education, for example.

In reality, almost all the evidence points to a much greater spontaneous level of cultural and linguistic diversity that arises whenever efforts to the contrary are halted. So we’d expect that, even if there’s a strong effort to construct and maintain a mutually intelligible lingua franca (or several) for the entire globe in such a society, we’d also expect see an unprecedented flourishing of entirely new cultural and linguistic practices at local scales. It would be a mistake, though, to use concepts like “nation” to describe such practices, just like it’s a mistake to use the word “state” to describe just any sort of collective, intentional coordination among people in a society. These are terms that, in their modern connotations, describe phenomena specific to the arc of class societies, from early agrarian empires to contemporary capitalism. The communist project is to end class society. Marx and Engels describe this as a return of sorts, at an entirely new (technological, demographic, ecological) scale, to the communistic relations that prevailed for much of human history. So whatever linguistic, cultural or geographic diversity we’d see in a communist society would need new terms to describe it or, at the very least, would be better described using categories from very different linguistic contexts—languages that emerged in nomadic pastoralist societies, or among hunter-gatherers, for instance. And the implications of such words would be very different.

You ask about “the desire for nation-states in a communist/anarchist future.” The answer here is very simple: there is no such desire. No self-respecting communist can look you in the face and say that there is still a “state” in communism. If they do so, they aren’t a communist in any sense of the word. And of course the anarchists have no desire for a state.

You ask about “the desire for nation-states in a communist/anarchist future.” The answer here is very simple: there is no such desire. No self-respecting communist can look you in the face and say that there is still a “state” in communism. If they do so, they aren’t a communist in any sense of the word. And of course the anarchists have no desire for a state.

Asia Art Tours: Lastly, I always remember what scholar Eli Friedman told me in our interview on the (then jailed) labor activist Xiangzi, that (I’m paraphrasing) we never know what international protests, dissent or direct action can effectively pressure China, so we just have to keep trying to find new pressure points.

- For activists working on labor, Xinjiang, Hong Kong, Tibet or other China issues what advice do you have for finding these pressure points, and how to use them when they are found?

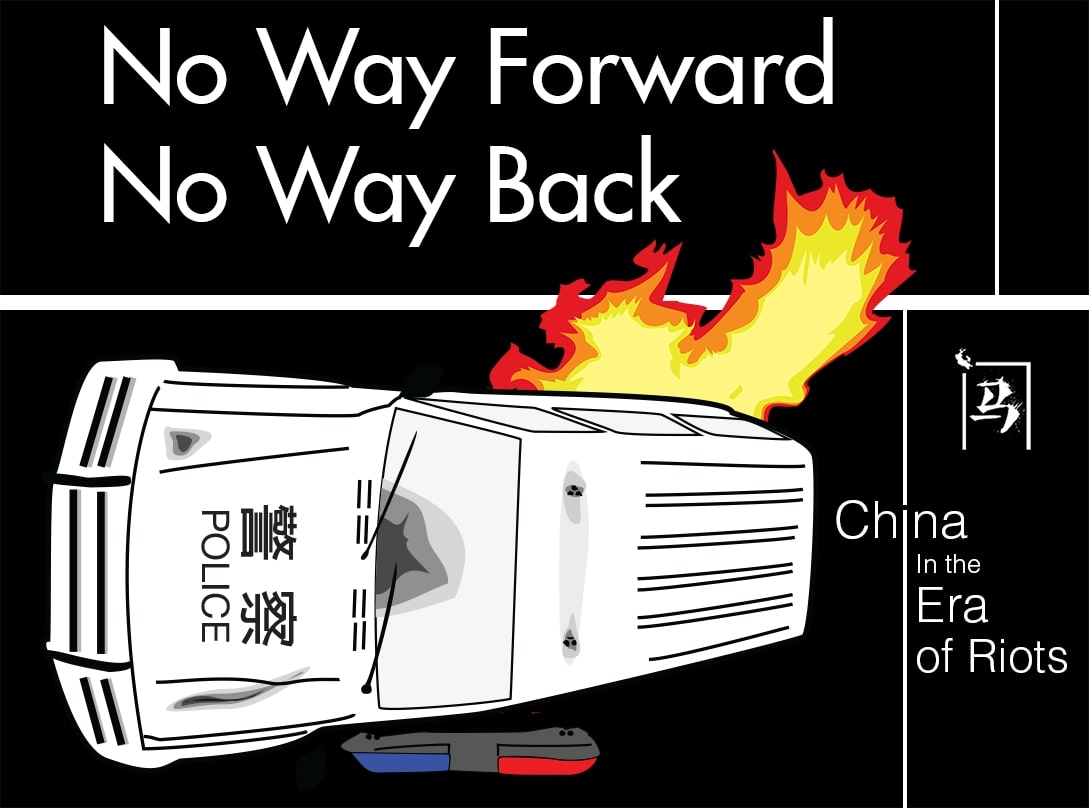

Chuang(闯): We think that any politics build around “pressuring” states or corporations to act better is going to be a losing game. Think, for example, of the giant global protests nearly two decades ago when the US invaded Iraq. There were enormous demonstrations in countries across the world. All kinds of diplomatic pressure emerged, many nations refused to join the US-led effort, anti-war groups sprouted up across the US itself and organized continually as the war began and dragged on. And it did absolutely nothing. States and the capitalists that sit behind them simply aren’t beholden to any rules of etiquette other than the ones they set for themselves. So, at the very best, an “effective” pressure point in this sense means begging that one fraction of the capitalist class punish another one for stepping out of line. This sort of appeal to the state is, effectively, what a lot of activists have been pursuing with regard to China’s crackdown in Hong Kong and its violent assimilationist projects in Xinjiang, Tibet and now Mongolia. Hopefully at least some of these activists are a bit embarrassed that those most ready to condemn China alongside them have been the most notorious of conservative politicians and domestic capitalists. This should be enough evidence that the idea of “pressure points” is a losing strategy, all around.

A lot of “socialists” today are also falling into this trap, though, from the opposite end: thinking that “anti-imperialism” means taking one side in what is really a building inter-imperialist conflict. They point to the hypocrisy of supposed leftists sharing articles by notorious, lunatic anti-communists like Adrian Zenz about Xinjiang, for example, or they share pictures of Hong Kong protestors waving American flags. These are easy targets, but they’re real targets, because so many people are making these basic mistakes and appealing to conservative forces who also oppose “Chinese authoritarianism” out of economic interest or because of their far-right evangelical ideology—despite the fact that these are the same people pushing for the passage of laws that illegalize far-left organizing in Europe and the US! But it’s equally idiotic to make the equivalent error in the opposite direction, jumping to the defense of the Chinese state, ignoring the crackdown on feminists, workers’ centers and Marxist student groups, or denying outright what is going on in Xinjiang.

Alot of “socialists” today are also falling into this trap, though, from the opposite end: thinking that “anti-imperialism” means taking one side in what is really a building inter-imperialist conflict.

Against all this, we think it’s more strategic to ask how and where communists can build real power in the midst of ongoing global uprisings in a way that doesn’t just get washed away into a generic push for “progressive” social policies, or roped into supporting one faction in a global inter-capitalist conflict. An important part of this is establishing lines of communication and mutual understanding while, in doing so, honing our understanding of global capitalism and its myriad conflicts. As mentioned above, this is really still a project in its earliest stages, but laying the groundwork is essential and we’ve already seen some great, inspiring results—for instance, some of the crossover effects between the uprising in the US and the one in Hong Kong a year earlier. Hopefully these sorts of interactions can gain depth and breadth over time, particularly as unrest continues to build worldwide.

And this is another important part of the project: participating in these cycles of unrest where you are at. If you really want to show “solidarity” with China, you’re wasting your time trying to appeal to the better nature of governing elites. If this is your idea of solidarity, you’ll ultimately be embarrassed by the results. You’d do better to go join the frontlines and defend the rioters burning down the police station and looting the Target in Minneapolis; kick back teargas canisters as the crowd smashes the luxury shops all down the Champs-Élysées; hurl bricks into the retreating line of riot cops in Bandung, Indonesia; storm federal buildings with the feminists in Mexico City. Wherever you are, the best solidarity is built from the blood and sweat that goes into making territories increasingly ungovernable, regardless of how well you intellectually understand, for example, that the struggle against racism in the US is structurally linked to the struggle against austerity labor laws in Indonesia and the struggle for so-called “democracy” in Hong Kong. Don’t waste your time looking for “pressure points” or petitioning your leaders. Instead, build power wherever and however you can.

If you really want to show “solidarity” with China, you’re wasting your time trying to appeal to the better nature of governing elites. If this is your idea of solidarity, you’ll ultimately be embarrassed by the results. You’d do better to go join the frontlines and defend the rioters burning down the police station and looting the Target in Minneapolis; kick back teargas canisters as the crowd smashes the luxury shops all down the Champs-Élysées; hurl bricks into the retreating line of riot cops in Bandung, Indonesia; storm federal buildings with the feminists in Mexico City. Wherever you are, the best solidarity is built from the blood and sweat that goes into making territories increasingly ungovernable

If you really want to show “solidarity” with China, you’re wasting your time trying to appeal to the better nature of governing elites. If this is your idea of solidarity, you’ll ultimately be embarrassed by the results. You’d do better to go join the frontlines and defend the rioters burning down the police station and looting the Target in Minneapolis; kick back teargas canisters as the crowd smashes the luxury shops all down the Champs-Élysées; hurl bricks into the retreating line of riot cops in Bandung, Indonesia; storm federal buildings with the feminists in Mexico City. Wherever you are, the best solidarity is built from the blood and sweat that goes into making territories increasingly ungovernable

All photos in this article are property of Chuang unless noted. Do not reproduce or use without permission.

For more with Chuang, please read their work here. You can also follow them on Twitter @chuangcn