Asia Art Tours is proud to present an interview with Lucinda Ping Cowing, the managing director of Kyoto Journal: Kyoto’s premier publication on both Kyoto and Asia’s Art and Artists. Asia Art Tours is happy to introduce you to Japan’s other literary figures on our “From Cover to Cover” Tour of Japan.

1. Please tell us about your background. How did you become involved with the Kyoto Journal?

A music career cut short led to my pursuit of the study of Japan and China — the other vague interest I had at the time, yet had very little first-hand experience of. I went to SOAS to do my degree, and ended up in Kyoto in 2010. I suspected I would not want to leave, and that’s just what happened.

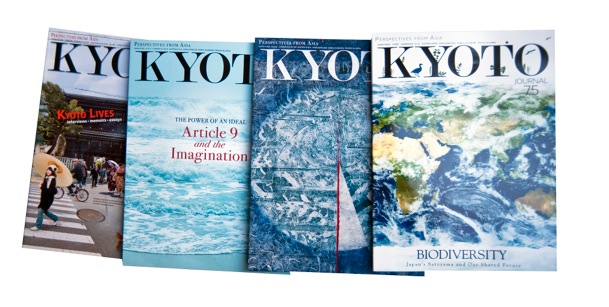

I was keen to make the most of my first year there and so wanted to have some activities or internships lined up before I flew out. I believe a quick Google search for the keywords: “journalism” “Kyoto” yielded the Kyoto Journal website. I honestly don’t remember what I read that so compelled me to contact them, but I met founder John Einarsen at Heian Shrine about a week after I arrived. John told me the story of how he first encountered Japan as a serviceman in the navy at the end of the Vietnam War, during which time he was part of a taskforce to clear Haiphong Harbor of mines. He explained how KJ came about, that his team had just brought out the 75th print issue, which was designed to be distributed free to delegates at the upcoming COP10 Biodiversity conference in Nagoya. The issue took a year to make and involved over 100 contributors — and like the core staff, were all volunteer. At the same time, he informed me that the sponsor of Kyoto Journal, the Heian Bunka Center, could no longer afford to keep us in print. The Heian Bunka Center was a project to support the arts throughout Asia set up by an extraordinary man called Shokei Harada, whose father Kampo Harada was a master calligrapher. Kampo made his fortune running calligraphy correspondency courses, with a school as far afield as New York, as well as beautiful anthropology museum just around the corner from the Shrine. Shokei-san sadly passed away a few years later, and a block of flats stand where the museum was. So, I have been involved with KJ ever since that meeting, albeit to varying degrees. I’ve been Managing Director since October 2017.

2. What is the goal of the Kyoto Journal, what stories are you trying to capture in the magazine.

We strive to be a reliable source of information on Asian culture and society that is at once both thoughtful and free of artifice or stereotype. The nature of the material is also generally not time-sensitive — issues of Kyoto Journal stay on the shelf to be revisited again and again.

KJ content is certainly diverse, such that it has been an issue for retailers in the past struggling to know where to place us! To give you some examples of some stories we recently featured:

- A remote Shiga workshop processes silk cocoons into strings for musical instruments

- Fashion photography documenting social change in post-soviet Kazakhstan

- A tribute to one of Tokyo’s iconic 60‘s hotels, remodeled for the Olympics

- An organization supporting amputees from unexploded ordinances in Laos

- The world’s most populous (yet virtually unknown) Buddhist monastic community

- Debuting a Noh play about Elvis

- The poignant poetry of a Chinese factory labourer

- The challenges of translating Japanese children’s literature

- A portrait of a Tibetan woman in Raj-era Indian society

We also want to provide a platform for the work of writers and artists from around Asia to be appreciated widely and thus open up opportunities for them — it is really wonderful to hear about a fiction author we published being offered a book deal or an artist having their work spotted by a prominent gallerist. What I’ve come to realize over the years is that Kyoto Journal is also sustaining a community and not just the other way around.

3. Can you describe what makes the Kyoto art scene unique and different within Japan? How would you describe the recent evolution and state of the scene?

There is a new generation now making their mark on traditional mediums — ceramics, lacquer, metalworking, textiles and so on — with a growing audience both domestically and overseas that appreciate and support their work. The appeal of functional “art” will withstand economic fluctuations or changes in trends. But the scene is unique for the same reason Kyoto is really, which is because it’s this highly concentrated centre of traditional culture in Japan, where one can quite easily find a obi maker that has been in business 300 years or a potter who is the 15th generation in his family. If you are not descended from a long line of craftspeople then you will certainly come to Kyoto to study.

For artists working in certain mediums, though, I believe it is hard to thrive in Kyoto. There is much more happening in Tokyo and Kanto. A talented photographer acquaintance confided that she has no customers in Japan for her work yet found success exhibiting in Europe, which did not surprise me.

There is no “Kyoto Biennale” but the Kyotographie International Photography Festival and Kyoto Experiment (specializing in contemporary dance and installation art) have become firmly established events in the city’s calendar. They grow in size with each passing year and I think they are making a great impact and helping to diversify the arts scene overall.

4. What philosophical values do you see in Japanese Arts, both traditional and contemporary that are important or useful in the modern world? What can they teach us?

The concept of mono no aware is a sensitivity to the fragility and impermanence of things, and it is hard not to notice it in the arts and literature of Japan. And, while it is tied in to Buddhist philosophy, it still holds relevance in a wider context regardless of one’s beliefs. It at the very least teaches one about living in the present and not taking the small things for granted; in fact finding the greatest beauty in life in these fleeting scenes that leave you breathless for a moment before disappearing again. There is an element of melancholy, in that all things must come to an end, but it teaches you about gratitude — gratitude for ever having experienced such a moment, or such beauty.

5. Lastly, could you tell us one story of Japanese Art or Culture that was personally moving for yourself?

5. Lastly, could you tell us one story of Japanese Art or Culture that was personally moving for yourself?

I am in possession of a precious furisode kimono that was given to me by a complete stranger during my first year in Japan. She was an elderly neighbour of ours and as is common in our area our front door was unlocked, so she like others would simply drop in, wander into our kitchen. She took one look at me (or perhaps we also exchanged simple greetings, I don’t recall), went home and came back a few minutes later with a rectangular package of folded washi paper, tied with orange knots. She said in her thick Kyoto accent that she had no use for it and her daughter had only ever worn it once for Seijin Shiki, the coming of age ceremony which takes place every winter for new 20 year-olds. It is of a white silk background with a mix of yuzen dyed and embroidered motifs. But it also has large portions of minute kanoko shibori tie-dyed dots, which must have been really painstaking to achieve. I shudder to think how much she must have paid for it, and I am still really taken aback by her generosity. Sadly I’ve not had the chance to wear it, and it is so extravagant that perhaps it would no longer be fitting for me to do so now that I’m in my late 20s! Maybe one day I will gift it to someone else.

For more information on the Kyoto Journal, please head to their website or Instagram. They are always interested in a good story!