I spoke to writer Eric Margolis on his fascinating profile of Kyohei Sakaguchi for The New York Times. Sakaguchi’s art and vision is one tied to mental health, sharing the commons and constructing a utopian vision of what Japan (and the world) could be.

Read our conversation below, and be sure to check out more of Eric’s writing on his website or in outlets like The Japan Times.

Asia Art Tours: Before discussing your feature on Kyohei Sakaguchi I noticed that in addition to art, climate change and natural disasters has been a major focus of your recent coverage. How has covering artists in Japan who’ve had to endure Climate Change, Covid-19 or disasters like Fukushima changed how you (yourself) process these forms of violence as a journalist?

Eric Margolis: I think that we’re creatures of our environment, and accordingly, environmental disaster shapes every feature of our lives and lived experience. With each passing year, I personally grow more climate conscious. Talking with people who have lived through the same disasters I have, as well as different ones that I haven’t experienced, reminds me of how universal environment is and how badly humans need to act and build our societies with a great environmental consciousness.

Now I believe that an article about any topic is also an article about climate change. It drives me crazy when I see reporting about some environmental news, like a drought or a farming issue, and fails to mention climate change.

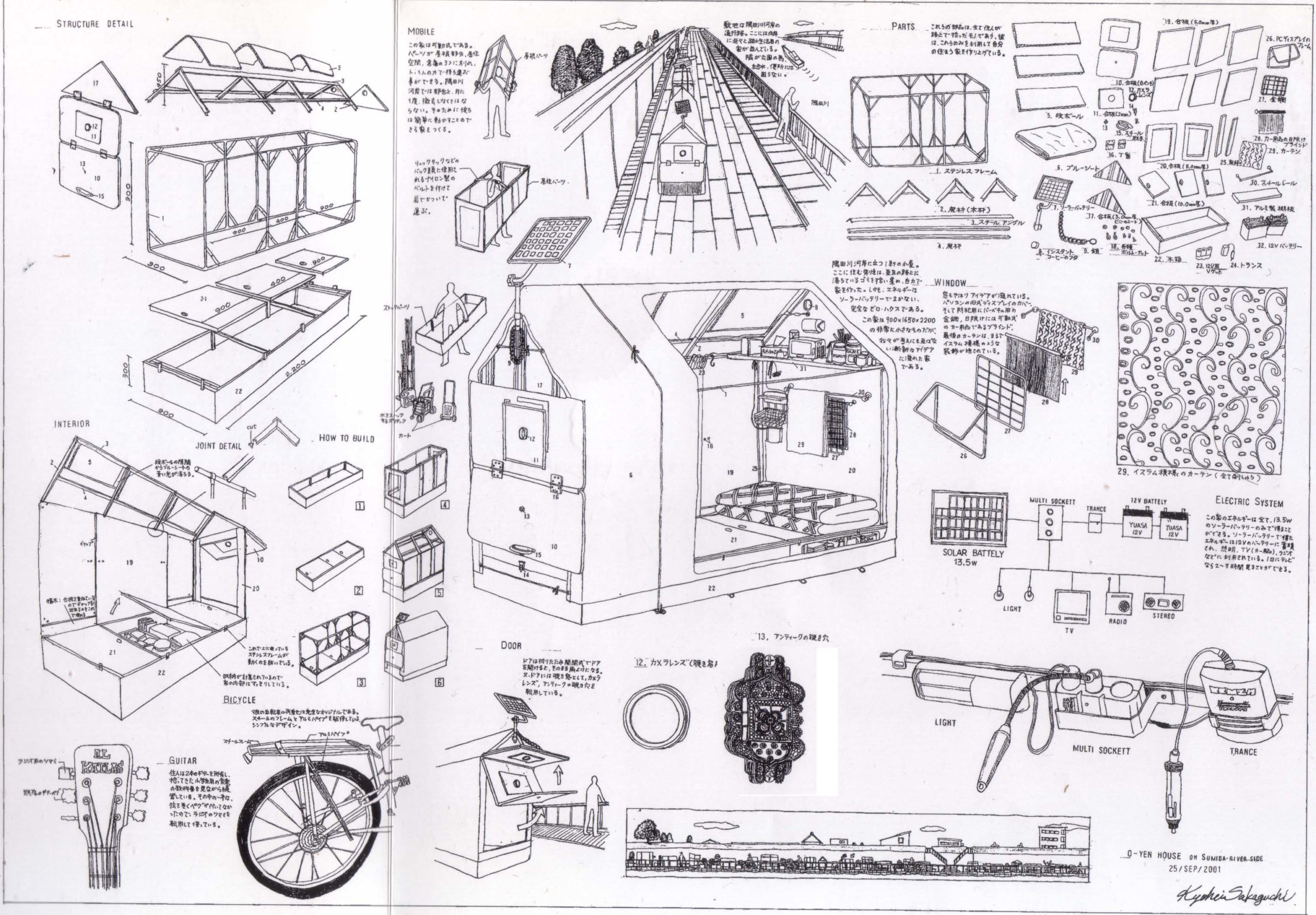

Blueprints for a ‘Zero-Yen House’ by Kyohei Sakaguchi, who has sketched out numerous designs for zero or low cost housing and has also built housing in Kumamoto for refugees from Fukushima: The Zero Center. Artwork Credit: KYOHEI SAKAGUCHI

Blueprints for a ‘Zero-Yen House’ by Kyohei Sakaguchi, who has sketched out numerous designs for zero or low cost housing and has also built housing in Kumamoto for refugees from Fukushima: The Zero Center. Artwork Credit: KYOHEI SAKAGUCHI

Asia Art Tours: Your feature on Kyohei Sakaguchi is laced with dark but accurate subtexts of our present era: Suicide, Natural Disaster, Homelessness, Capitalism, Private Property and Mental Health Crisis. What are the larger societal issues within Japan that have led to Sakaguchi’s popularity and importance as an artist? And what do his fans say about why they find such hope, beauty or solace in Sakaguchi’s art?

Eric Margolis: Japanese society has a lot of inertia and is slow to change, so Sakaguchi’s important questions about the way late-capitalist societies function strikes a deep subconscious chord. I don’t think his outlook and work would resonate with as many people as it does if he was physically trying to round up the proletariat, so to speak. Instead, his approach speaks to the possibility of a better world. A world where we are all housed, where we can communicate freely to overcome our mental challenges, and where we are all unreservedly altruistic.

Sakaguchi’s unbridled altruism is especially inspiring. His life and work reminds me of an idyllic rural society, almost out of the Torah: when someone hungry turns up on your street, you house them and feed them. It feels impossible to be altruistic like that in a world with so many crises, but Sakaguchi proves that it’s possible with a little creativity.

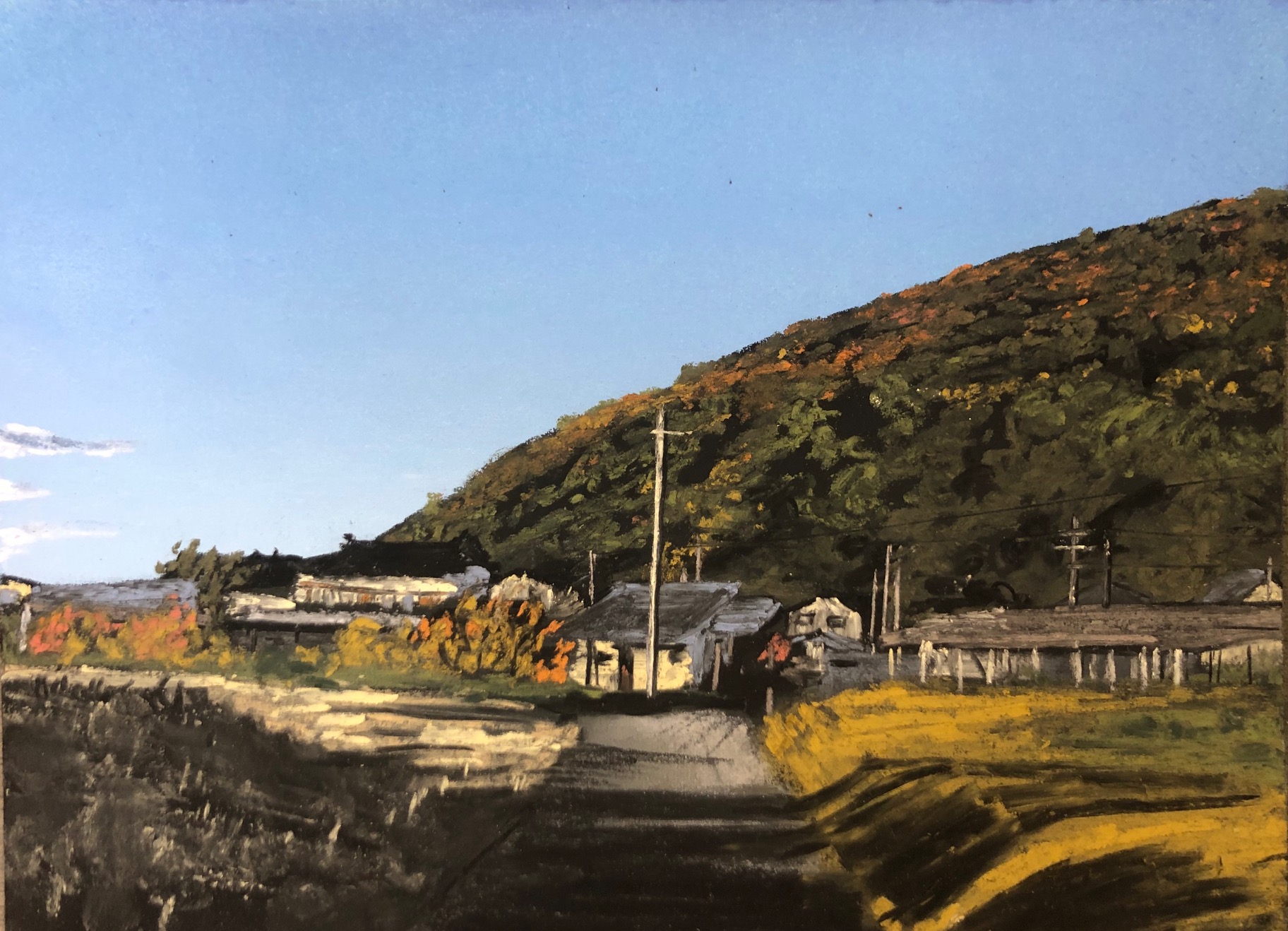

Still-life painting by Kyohei Sakaguchi of Japan’s countryside. Sakaguchi has found the slower pace of Kumamoto and the surrounding countryside to be enormously generative for his artwork. Artwork courtesy of Kyohei Sakaguchi.

Still-life painting by Kyohei Sakaguchi of Japan’s countryside. Sakaguchi has found the slower pace of Kumamoto and the surrounding countryside to be enormously generative for his artwork. Artwork courtesy of Kyohei Sakaguchi.

Asia Art Tours: A major focus of Sakaguchi’s work has been on documenting (and building) ‘Zero-Yen’ Houses. In the context of Japan’s low-homeless rate and literally giving away abandoned housing, should we view Zero-Yen houses (and Sakaguchi’s interest in them) as an artistic project? Or do his Zero-Yen houses point to larger societal problems and potential solutions for the structural violence of capitalism?

Eric Margolis: I think the Zero Yen House project is an artistic project that points to real solutions. For one, Sakaguchi was interested in the creativity of designs. Unhoused people have art, they personalize their surrounding, they make a place their own. But, as Sakaguchi said in the article, the fact that highly developed economies such as Japan and the U.S. have such large homelessness problems is very backwards and primitive. With such technology and wealth and infrastructure, it seems like a small task to provide private places to live. (Of course, it’s not a small task, but it’s certainly doable).

With so many abandoned houses in Japan, Sakaguchi’s idealism is actually quite close to reality. I think a lot of people, and in growing numbers, appreciate Sakaguchi’s way of life. Live in an old house, a cheap one. Patch it up with your own labor. Why use so many resources to create something new when you can live in the environment out of something that’s already there? And you can still make an old house your own.

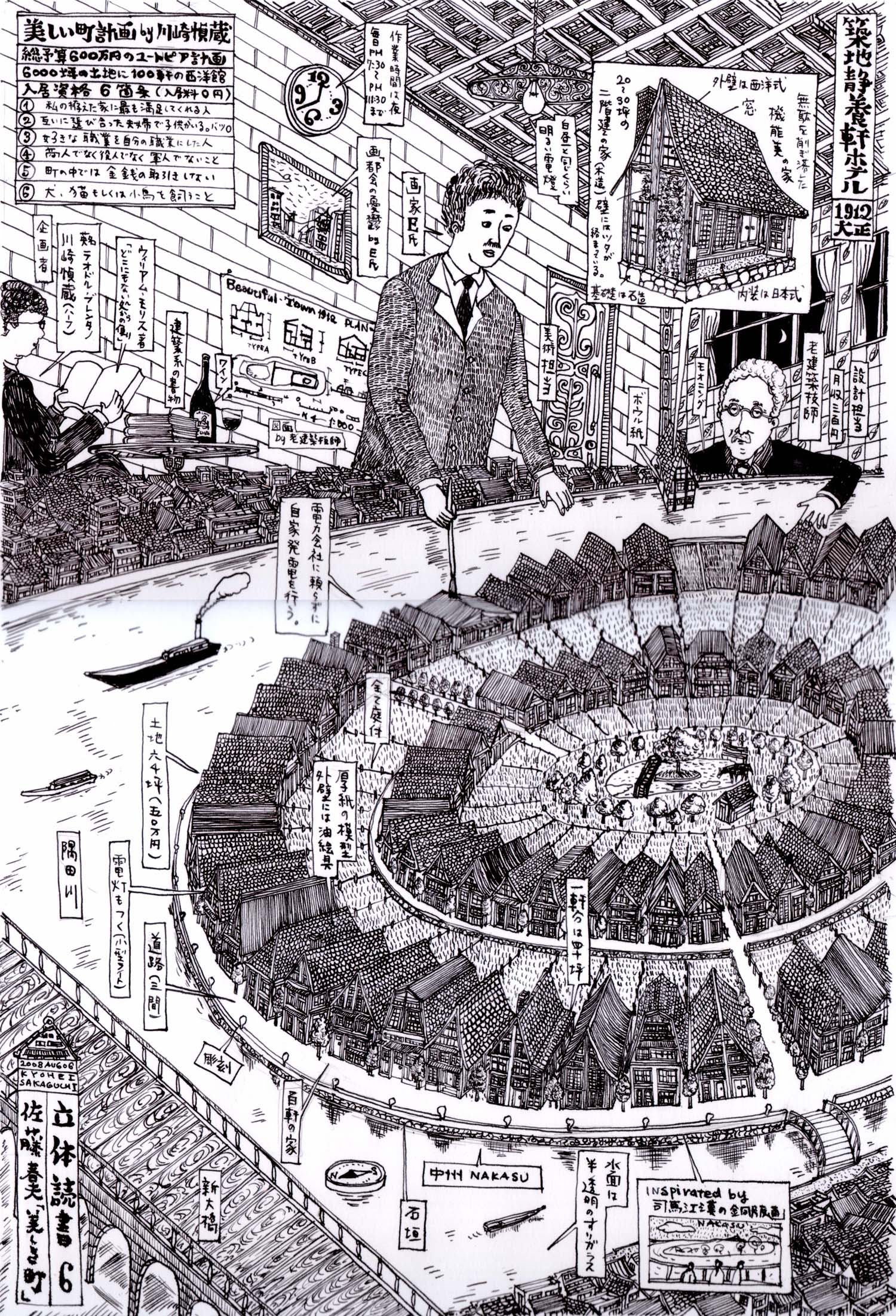

A theme consistent to Sakaguchi’s work is imagining utopian homes, communities and nations. He has written several books on these topics and illustration is another form of artwork that he uses to express his vision for a better world. Illustration Credit: KYOHEI SAKAGUCHI

A theme consistent to Sakaguchi’s work is imagining utopian homes, communities and nations. He has written several books on these topics and illustration is another form of artwork that he uses to express his vision for a better world. Illustration Credit: KYOHEI SAKAGUCHI

Asia Art Tours: Throughout your feature, Sakaguchi rejects titles and seemingly the fame, status or prestige that comes with being a famous artist. Do you see this rejection of fame in anyway connected to the vision of his art and his larger visions of society?

Eric Margolis: Sakaguchi is simply a grounded person who loves what he does. For all the ways that his work intersects with social issues, Sakaguchi is very much an individualist. He wants to live his own fulfilling life, helping other people along the way in his own way. Fame or prestige doesn’t really interest him. As I quoted him as saying in the article, art is a way to survive for him. He creates because, well, that’s what he does!

Of course, the content of Sakaguchi’s work does connect to a larger picture of society when you start to unpack it. I would call it a vision of an altruistic self-subsistence, a world where we all have the financial and health leeway to survive by doing what matters most, including attending to the needs of others. The idea is almost a contradiction because Sakaguchi aspires to grow his own food, make his own medicine, and build his own house, while at the same time, I’m sure that he would advocate for a society in which the government helps to provide those same things.

But this contradiction is just a part of his deal–we’re talking about a complicated individual who produces a great deal of work to get by, both financially and mentally. There’s not an easy way to sum up a person’s work into a singular ideology. He’s not an artist with a patron, who can spend five years writing a novel to deliver perfect philosophical clarity–his art is his bread and butter, so he makes as much of it as he needs.

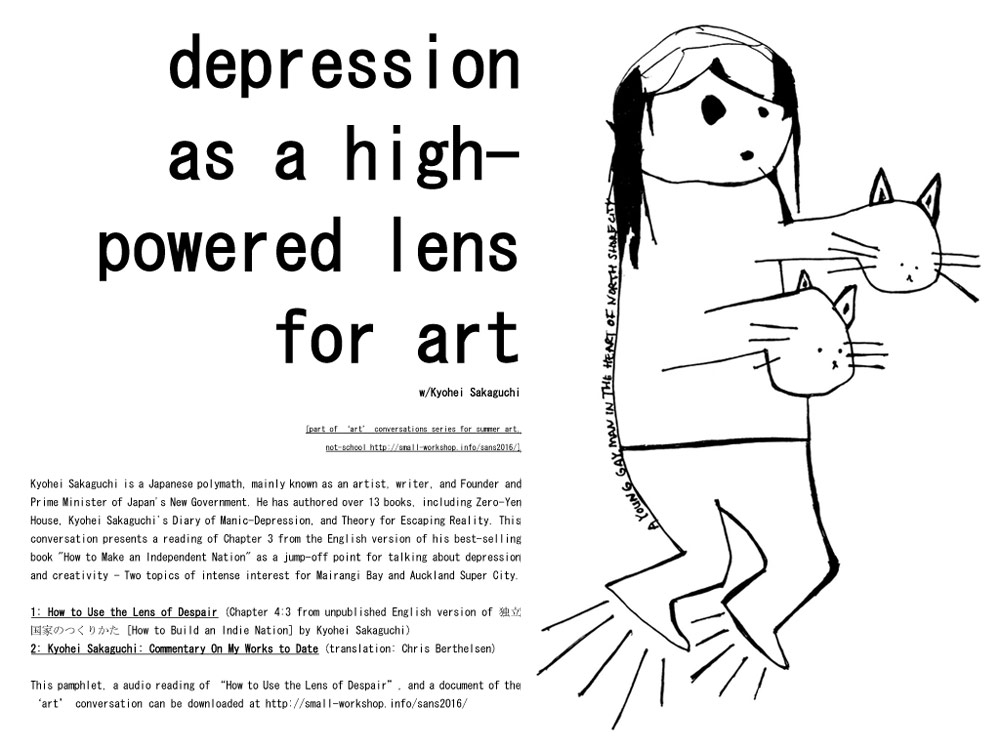

Kyohei Sakaguchi has always been transparent and open about his own mental health struggles and how they’ve influenced his art. Sakaguchi’s openness is a rarity in a Japan and world that still holds social stigmas against mental health issues. Photo Credit: A SMALL WORKSHOP

Kyohei Sakaguchi has always been transparent and open about his own mental health struggles and how they’ve influenced his art. Sakaguchi’s openness is a rarity in a Japan and world that still holds social stigmas against mental health issues. Photo Credit: A SMALL WORKSHOP

Asia Art Tours: Fame aside, Sakaguchi has made himself vulnerable and intimate in a truly public way by creating his own Suicide Hotline. Could you explain why Sakaguchi created this project and what underlying problems with mental health resources in Japan does Sakaguchi’s Hotline point to?

Eric Margolis: The conversation around mental health in Japan has been slow to get off the ground, and the nation’s struggles with suicide have been well-documented. Clearly, resources are insufficient. And Sakaguchi personally experienced this dearth via his own experiences with bipolar disorder. He experienced poor suicide hotline resources, so he made his own. It’s very much like him, and I think the fact that so many people call him is a total alarm bell going off. Clearly there is a very strong need for mental health resources in Japan that isn’t even close to being met.

To help those who felt social stigma about depression, suicide and mental health, Sakaguchi self-published his phone number so anyone could call him to discuss their own mental health issues. Photo Credit: KYOHEI SAKAGUCHI, TWITTER

Asia Art Tours: And to then complicate this question, should the amateur nature of Sakaguchi’s Suicide Hotline (and other projects like his ‘Make your own Medicine’ book) cause us to reconsider larger problems in health care? In Sakaguchi offering us an alternative vision about what health care could be? (Something more personal, intimate, horizontal and available for free)?

Eric Margolis: Sakaguchi is careful to say that he isn’t a doctor or a substitute for one, but I do think you’re on to something here. Our mental health crisis isn’t only a problem of medical resources and access. It’s a deeper problem with society. If we had more access to housing, if we were more economically secure, if we weren’t as isolated, if education was kinder and more agile, if we could make livelihoods the way we chose, would the mental health crisis both in Japan and around the world be as severe? To me, the answer is a loud and clear no.

The solar-powered ‘Zero-Yen’ House’ designed by Kyohei Sakaguchi. He also built a center for refugees from Fukushima: The Zero Center. Read more about the ‘Zero-Yen House Project’ and ‘ The Zero Center‘ here. Photo Credit: KYOHEI SAKAGUCHI

The solar-powered ‘Zero-Yen’ House’ designed by Kyohei Sakaguchi. He also built a center for refugees from Fukushima: The Zero Center. Read more about the ‘Zero-Yen House Project’ and ‘ The Zero Center‘ here. Photo Credit: KYOHEI SAKAGUCHI

Asia Art Tours: The world is facing incredible problems and the structures in place seem to have no answers beyond continuing on the same path. What can we learn from Sakaguchi about how we might solve these problems using different methods? And for you personally, what role do you see artists like Sakaguchi having in helping us save the world?

Eric Margolis: Saving the world is such a floaty concept, but weirdly, artists like Sakaguchi can clarify exactly what saving the world means. If me and my neighbors were housed and lived in tight-knit communities without risk of isolation or impoverishment, while freely pursuing our creative passions with fresh-grown local food–that sounds like a world saved to me. The cumulative sum of Sakaguchi and his work speaks to this possibility of a ‘saved world.’

In terms of how to actually solve these problems, I think we can learn from Sakaguchi to play to our strengths. I’m going to use my journalism as much as I can to raise these issues of environmental crisis, inequality, and mental health. I hope to do more literary translation in the future, and when I do, I’m going to make sure my approach and material highlights those same essential issues. The best thing about examining Sakaguchi’s work like we’ve done in this interview and as I did in the article is that it comes back around to doing what you love. We all have a role to play in making the world a better place, but it doesn’t involve being a martyr or endless suffering. If each of us live our lives to our own potential, I don’t see why we can’t collectively solve many of these problems.

Abstract painting by Kyohei Sakaguchi. Sakaguchi is a polyglot who works in a variety of painting styles as well as being an accomplished musician, architect and author. Artwork courtesy of Kyohei Sakaguchi.

Abstract painting by Kyohei Sakaguchi. Sakaguchi is a polyglot who works in a variety of painting styles as well as being an accomplished musician, architect and author. Artwork courtesy of Kyohei Sakaguchi.

Asia Art Tours: I’m always fascinated by Arthur Conrad Doyle’s notion that detectives should focus on ‘dogs that don’t bark’. From your experience as a journalist, do the stories that ARE NOT being published about Japan offer us insight into the current limits of journalism on Japan?

Eric Margolis: I touched on this previously, but I’m interested in societal inertia in Japan. Why is society so slow to change? There are cheap answers here: because old men tend to be in power, and because Japanese culture discourages change, even when it’s obviously the right thing to do. No one opened the windows in my girlfriend’s company’s office even though it was sweltering in there, because no one thought they had the authority to do so.

Japanese society has shown such amazing resilience and has produced so many incredible artists, thinkers, artisans, and infrastructure. I think there needs to be more work that excavates the architecture of Japanese society and puts the ‘why’ behind the what. A lot of people smarter than me have talked about how trends in Japan tends to augur those in the west–everything from cell phones to loneliness–and that we haven’t properly bothered to learn from what Japan went through. It’s time to start learning.

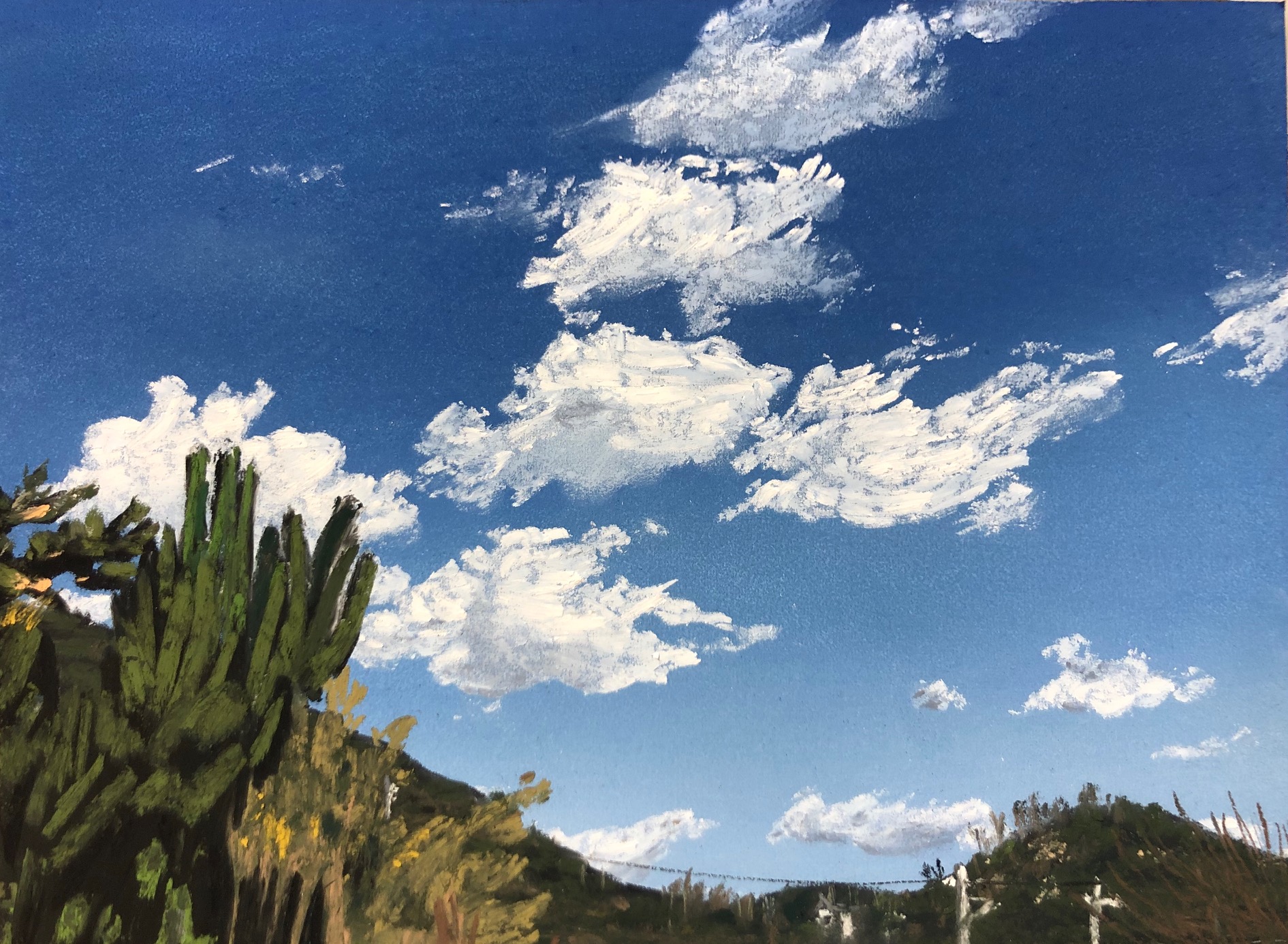

A still-life painting of Japan’s countryside sky. Artwork courtesy of Kyohei Sakaguchi

A still-life painting of Japan’s countryside sky. Artwork courtesy of Kyohei Sakaguchi

Asia Art Tours: And if money and having to survive as a writer/journalist was no object, what would be the stories you would want to focus on in your reporting on Japan?

Eric Margolis: I would want to keep reporting on climate change, but above all, honestly, artists like Kyohei Sakaguchi. It’s very hard to take the time to report on trends and developments in art and literature, especially a long feature, when it’s unclear how much they will play into the current events that rule the news and click-bait cycle. So getting to report on Sakaguchi-san was a dream come true for me. The work of artists, writers, translators, architects can teach us so much about important social issues, so it was amazing to see those two sides come together in this New York Times article.

‘Selfie’ of Kyohei Sakaguchi in his Kumamoto Garden. Photo courtesy of Kyohei Sakaguchi.

‘Selfie’ of Kyohei Sakaguchi in his Kumamoto Garden. Photo courtesy of Kyohei Sakaguchi.

For more of Eric Margolis’s unique reporting on Japan and his translation work you can find his website here or follow him on Twitter @ericdmargolis