Joining me to discuss China today are Biyi and Yan, the founders of the Elephant Room. They do an incredible job translating stories of internet culture, celebrity and politics for an English-reading audience. I can’t recommend them enough! Part 2 of our interview can be found here.

Asia Art Tours: What is the Elephant Room, how and why did the project start? And how has the project evolved as China has changed?

Elephant Room: is a personal media project about China that started in early 2017 (I wrote a long post about it back then). When I moved back to China after many years studying and living in western nations, I noticed there was a gap in the English media world regarding China: most China news were reported by foreign correspondents or China-watchers, who were enthusiastic, dedicated, but lack a local undertone. This got me thinking: shouldn’t there be a Chinese voice in China reporting? If so, why not do it myself? I was my no means a professional journalist, but with a long-held passion for media and story-telling, I believed there was a space for my personal contribution in helping people to better understand China.

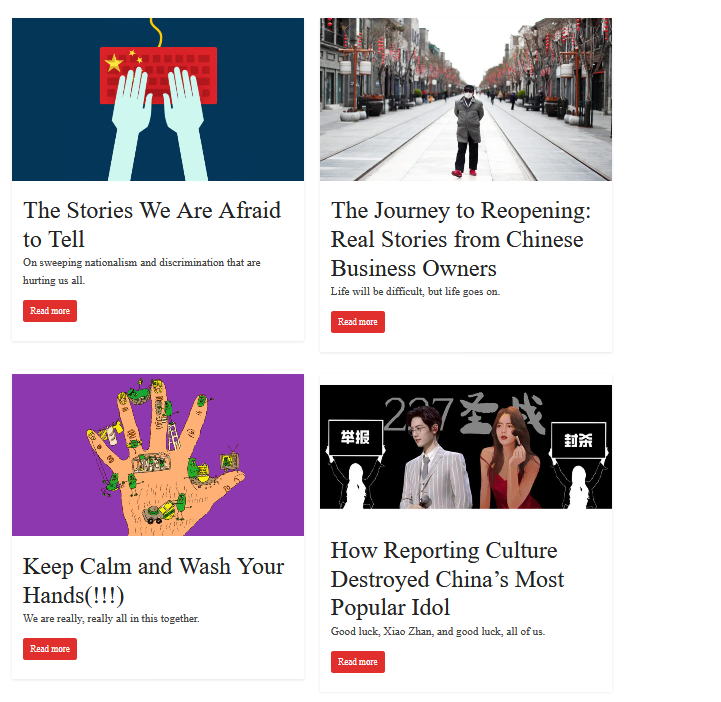

So Elephant Room was born. I invited my best friend Yan, who shared a similar cross-cultural background with me, to become co-authors for the project. Together we built a website, started a mailing list, and began to write. We focused on topics that particularly drew our interests such as consumerism, internet, entertainment and youth culture, and tried to use each topic as an entry point for a deeper look at today’s Chinese society.

To date, we have published over 80 articles on Elephant Room. In terms of how the project has evolved over the past three years, I guess perhaps two points worth nothing:

(Elephant Room covers stories on China’s internet and pop culture that we haven’t seen handled anywhere else.)

First, as censorship and speech control tightened in China, we became more cautious about our writing (for more of our thoughts, you can check out this post). As much as we don’t want to admit, the fear is real, and as two Chinese citizens with jobs and families all in China we have to be careful of the consequences of our own words. For a while we were really concerned to the extent that we stopped writing; but this year we decided to continue telling our stories despite the potential risks (finger-crossed!!).

And then there are those bigger changes over the past two years, not just in China but globally: the rise of populism, the deterioration of U.S-China relations, the collapsing of modern liberalism values, de-globalization and more. All of these shifts have led us, two self-considered liberal, open-minded females to become frankly more depressed. Where is our world heading to, is there still space towards a better future (which must be built upon cross-cultural exchanges and open conversations as we believe)? We carry these big, heavy questions with us now as we write on. (Biyi)

AAT: Just as I don’t consider myself white, I consider myself Armenian and Lebanese, I’m wondering within China do we see this same strong sense of local identity? For example would most people consider themselves a 四川人 first and 中囯人 second?

ER: This is an interesting question. I think the identity for Chinese varies depending on who they are comparing themselves to. When they are talking in a global perspective, they consider themselves Chinese first. But when they are talking to people from other provinces, which is when being Chinese is a given for everyone, they consider themselves as 四川人 or 北京人

As Biyi and I are both 汉族, and we are surrounded by 汉族, racial ethnicity rarely comes to mind in our daily lives. But I am sure those being in minor ethnicities are more conscious about their ethnicities as a self-identity. (Yan)

AAT: How would we apply these questions to places like Guangzhou’s “Little Africa”, Indigenous areas of Yunnan, or the major sites of state violence in Xinjiang or Hong Kong? Why have the majority of Chinese citizens, who do feel very strongly about their local identity, been largely silent or (for those more jingoistic) even supportive of the erasure or forced transformation of these local identities?

ER: I don’t think racial identity is the most constructive framework in understanding issues such as Guangzhong and Xinjiang in today’s China. Of course race plays a role, but it does not explain Chinese peoples’ mindset in understanding these issues. People support the repression in Xinjiang and Hong Kong for reasons such as social stability, security, and most importantly, for the consolidation of national sovereignty, which is considered the most important priority for both the government and the people. Growing up, we were educated that ancient history of China was one filled with invasion and territorial separation, which led to suffering of people. Under this mindset, Chinese people today consider “territorial completeness” the most important matter beyond everything.

(Guangzhou’s African population is a complex and deeply misunderstood part of the community. Photo: Weibo)

In terms of the conflicts in Guangzhou’s African community, I am afraid we are not knowledgeable enough yet to speak about the issue. Two things we believe are true though: 1) Most Han Chinese do hold a negative view toward people of non-yellow and non-white skin colors, but the reasons are more complex than just “racism”. 2) Due to tight control on local activism, few Chinese citizens have the opportunity to express their honest attitudes towards these matters. (Biyi)

AAT: Could you discuss the case of Qiu Chen? Would anyone receive the ‘public guillotine’ she did for supporting Hong Kong? Or was she singled out due to her class position, fame or LGBTQ identity?

And within the LGBTQ communities of China, what was the reaction to Qiu Chen’s treatment? Is there a sense of wanting to speak out for her, or does “homo-nationalism” (being Chinese Citizens first and LGBTQ second) lead to many in China’s LGBTQ communities, actually supporting the punishment she received?

ER: Qiu Chen received this public guillotine particularly because of her huge fame. Not everyone who speaks publicly on matters of Hong Kong would receive this amount of attention. Often times netizens with little public influences (we call them 小透明) would have their accounts completely erased by automatic censorship (炸号) before their posts received mass attention.

(Chinese Quiz show celebrity Qiu Chen, who was publicly destroyed by State Media for her earlier support of Hong Kong)

The following question is very interesting. We haven’t seen any signs of homo-nationalism on the Chinese internet, largely because the topic of LGBTQ itself has such narrow spaces for expression, let alone for those in the LGBTQ community to discuss their opinions on nationalism.

Would a member of the LGBTQ community, who is being so suppressed and mistreated in China, love their country so much that they support the punishment of fellow member of the same community? If such circumstance does exist, I would love to interview this person to explore their logic and psychology. (Yan)

AAT: Could you explain for us who was Jiangshanjiao? And how does she fit into a larger pattern of the Party trying to link female identity to the State? What led to women becoming so angry with this propaganda figure that they were willing to risk directly criticizing the state?

And what does Jiangshanjiao’s ‘ public execution’ represent in terms of larger contradictions that the state has yet to resolve in terms of how it tries to relate to, or control female identity in China?

ER: Jiangshanjiao, along with Hongqiman, are a pair of “virtual idols” created by the Communist Youth League with the aim to attract young Chinese netizens. These two animated characters were launched on Weibo in mid-February (during the height of Covid-19), and received massive disgust. The Youth League deleted all of the relevant posts soon.

(The idol Jiangshanjiao 江山娇,released during the peak of Covid-19’s impact on Wuhan, faced a huge backlash from China’s Public)

In terms of why women were so angry, well, as we mentioned in our article, everyone was angry back in February. It was a time that anxiety and anger were looming in everyone’s’ life; the battle with the pandemic had just started, and people were feeling unsatisfied with many of the governmental conducts. Everyone was looking for ways to participate in public discussions online, and Jiangshanjiao became the center of the target. She was the wrong character, launched at a wrong time.

I don’t think Jiangshanjiao is a strong example of the party trying to “link female identity to the state” (She was launched with a brother Hongqiman remember!) Rather, it was an example of the government trying to appeal to the young generation as a whole. As I said, everyone was angry back then, and Jiangshanjiao’s launch particularly outraged those who were dissatisfied with gender equality and women’s rights. The fact that the whole incident turned to be a feminists’ campaign doesn’t mean it started as a feminist issue, I ‘d argue this way. (Biyi)

Part 2 of our interview is out now. You can visit the Elephant Room Project here: http://elephant-room.com/