In Thailand, hundreds of thousands of protestors have been demanding freedom from the systems of Monarchy (Sakdina) & Military Dictatorship that denies them freedom.

To better understand the nuances of the Thailand protests, how they connect to regional and global struggles, I was thrilled to speak to Thiti Jamkajornkeiat. Thiti has written eloquently on the protests and was kind enough to join me for an in-depth conversation. Read part two here

Asia Art Tours: Throughout your article for Spectre you do a great job highlighting both the theory and praxis behind the Thai Protests, beginning with this stirring passage:

Wearing a red blouse on the stage under red spotlights – the color symbolizing anti-dictatorial dissent – 22 year-old Panusaya “Rung” Sithijirawattnakul announced the electrifying 10-point demand for monarchical reforms that transcended all limits of Thai politics.1 . . . Rung ended by shouting in Thai, “Down with Feudalism (sakdina), Long Live the People (pracharat)!” while throwing her written scripts into the air, creating an astonishing spectacle. Rung and the audience repeated the chant in unison three times while displaying the iconic Hunger Games three-finger salute. Since then, this slogan has emerged as one of the most popular Twitter hashtags and protest chants. Rung adapted this phrase from Khrong Chandawong, a leftist MP from Isaan, who originally yelled “Down with Dictatorship (phadetkan), Love Live Democracy (prachathipatai)” before being executed by firing squad in 1961.

I first learned about the historical importance of symbolism in Thailand’s protests through the work of Photographer Manit Sripoochoom. Besides Rung’s symbolism what other prominent examples are there of Thailand’s current protesters making reference to the protesters of the past? And how important has this historical memory been in fueling the current protests?

Thiti Jamkajornkeiat: I would begin my response by admitting upfront my own limitation in tackling these thoughtful interview questions; I am observing the protests from abroad and would likely miss many specific protest tactics—whether mundane and extraordinary—on the ground. I am answering the inquiries with this spirit of a critical observer—close enough to notice general patterns and deduce the political logic, but too far to grasp the specifics or spot remarkable resistance in areas marginal to media attention.

Undeniably so, in a country that propagandizes royal deeds as national history—what Thongchai Winichakul has long conceptualized as hyper-royalist nationalism—the protestors unlearn and re-learn the history of Thai radicalism as they search for deeper and wider connections that help sharpen their political causes. I allude to hyper-royalist nationalism first to make a point that even to just recuperate those anti-royalist and other dissident memories in a heavily propagandized society is already a challenging task on its own, not to mention inheriting and communicating them to the public.

(Disappeared organizer and satirist Wanchalearm Satsaksit, abducted in Cambodia many suspect he has been murdered at the behest of Thailand’s Monarchy. Photo credit – Wikipedia)

(Disappeared organizer and satirist Wanchalearm Satsaksit, abducted in Cambodia many suspect he has been murdered at the behest of Thailand’s Monarchy. Photo credit – Wikipedia)

From my own observation, I see one particular transgressive figure that stands out as a mobilizing symbol: the Thai state’s dead victims, which is less about invoking past uprisings than illustrating the failures of all of us in abolishing this necropolitical system even now. More state-involved deaths can occur, and, in fact, they are encroaching upon all the anti-dictatorial protestors. I do not think this is the state’s scare tactic that I internalize or whether I give too much credit to “the state” as long as the state has never been held accountable for its violence against the people nor officially relinquished this “prerogative” to kill.

The rhetorical question I often hear as a motivation for the resistance is, “why does one need to be murdered by just having or expressing a differing opinion?” By merely criticizing the monarchy, Thais might have to pay with their lives, and in stealthier cases, die a gruesome death. Such a question shakes the Thai society, built upon forced uniformity that sustains a profoundly hierarchical structure, to the core and musters courage for some to take to the streets. These dead victims—i.e., Wanchalerm Satsaksit, Chatchan “Phuchana” Bubphawan, Kraidej “Kasalong” Luelert—became martyrs around which Thai protestors at some rallies gather, not just to express rage against the death-dealing system, but grief for the deceased.

Asia Art Tours: The prominent Thai dissident Giles Ji Ungpakorn wrote a response to your piece titled: ‘Down with Thai Capitalism! The People Against the Military Dicatorship!’ Turning to Thailand’s capitalists who are part of the 1% ( CP’s Dhanin Chearavanont, Red Bull’s Chalerm Yoovidhya and so on) how and why has this elite class helped to perpetuate the Sakdina system?

And how (if at all) are they still made to subordinate themselves to Sakdina? On this second point I’m curious if you see the military/monarchist-led coup against former PM and Billionaire Thaksin Shinawatra as what happens when Capital tries to break free from Sakdina?

Thiti Jamkajornkeiat: I, in fact, do read Ungpakorn’s piece as a great supplement to my piece because he has achieved what my article—which aims to systematize and think along with the protestors’ discourse—does not do, namely, suggesting what analyses have been missing in the struggle. Similar to Puangchon Unchanam, Kengkij Kitirianglarp, Songchai na Yala (pseud.), and Jim Glassman, I understand the Thai monarchy and military in the 20th century as capitalist institutions—whether you would call them neo-feudal capitalists, bourgeois military, or, as Glassman puts it, lazy capitalists who intentionally “underdevelop” the country the same way, Walter Rodney tells us, European colonizers “underdevelop” the colonies. The stickier problem that requires further, much further, both empirical and analytical, research is the relationship between these three M’s—money, monarchy, military—in dominating the Thai society through a combination of coercion and consent.

The rhetorical question I often hear as a motivation for the resistance is, “why does one need to be murdered by just having or expressing a differing opinion?” By merely criticizing the monarchy, Thais might have to pay with their lives, and in stealthier cases, die a gruesome death. Such a question shakes the Thai society, built upon forced uniformity that sustains a profoundly hierarchical structure, to the core and musters courage for some to take to the streets.

(Poster depicting corruption behind the wealth of Thailand’s Monarchy. Photo Credit – Prachatai)

(Poster depicting corruption behind the wealth of Thailand’s Monarchy. Photo Credit – Prachatai)

Definitely do not cite me on this as my specialization is not on Thai capitalism; My impression is that the 1% exchange their wealth with the sakdina for patronage, network, and facilitation to do businesses without the state’s bureaucratic hassles. I am sure some sociologists or anthropologists would have already studied this, and there might be more to what I am about to say; I see this symbiotic relationship between the 1% and the sakdina as a persistence of the tributary transaction where those under the “big boss” or “mafia”’s influence (this idea I got from a conversation with Thongchai) submit tributes to the center to receive its protection and connection—something quite akin to the Chinese guanxi albeit with a clearer understanding of an unequal relationship.

For the Thaksin case, it is when Ungpakorn’s Trotskyist and Watcharabon Buddharaksa’s Gramscian analyses are very relevant. Ungpakorn, in particular, said the coup against Thaksin was a struggle of capitalist competition between the more cautious traditional investor inheriting inter-generational wealth and a risky telecommunications tycoon accumulating enormous wealth from tapping into the booming business sector. Hence, I understand the coup against Thaksin as less about the capital flight from the sakdina as they are players in the same capitalist field than the eradication of an emerging hegemony that succeeded in rebuilding Thailand in the aftermath of the 1997 financial crisis—one that can build a better consensus between new economic elites, technocrats, and the working, especially regional, masses.

If left without intervention, Thaksin’s hegemony might gradually outweigh Bhumibol’s consensus point by point. In terms of mass politics, Thaksin’s populism became crystal clear, especially in the north and northeastern regions. His capitalist policies and social welfare were more attractive to the grassroots than Bhumibol’s sufficiency economy and exclusive welfare for the bureaucrats (or kha ratchakan ‘servant of the king’s duty’ in Thai). Lastly, Thaksin’s modernization disenchanted much of the royal traditionalism long dominating the Thai socio-cultural spheres.

The stickier problem that requires further, much further, both empirical and analytical, research is the relationship between these three M’s—money, monarchy, military—in dominating the Thai society through a combination of coercion and consent.

( 2010″Red Shirt” protest at Ratchaprasong intersection. The red shirts organized mass rallies across Thailand to mark the ousting of former Thai prime minister Thaksin Shinawatra. Photo Credit – Wikipedia)

( 2010″Red Shirt” protest at Ratchaprasong intersection. The red shirts organized mass rallies across Thailand to mark the ousting of former Thai prime minister Thaksin Shinawatra. Photo Credit – Wikipedia)

Asia Art Tours: In reading your article, for many of the protesters (and we’ll bring up a counter-example shortly) it seems anger is mostly directed at capital controlled by King Vajiralongkorn:

King Vajiralongkorn transferred the Crown Property Bureau’s entire portfolio of an estimated $40bn. to himself in 2018. . . On numerous occasions, the protestors yell, display, or graffiti the word “phasi gu,” meaning “my fucking taxes.” Protestors also frequently call for boycotting on anti-democratic, pro-establishment corporates. For example, during the plaque installation rally on September 20, youth leader Penguin called for a boycott of Siam Commercial Bank (SCB), “a money pot of feudalism” in which the monarch is the biggest shareholder. On November 25, two months later, an estimate of 15,000 protestors rallied outside of SCB headquarters in Bangkok to, in the organizers’ words, “reclaim assets that should belong to the people.

In other global protests we see regime-aligned businesses targeted by protesters. I wanted to ask if it’s possible for such targeting to be effective? What separates an ‘SCB’ Bank from a German Bank that allows the King to move money into Bavaria? How is it possible to separate the ‘king’s wealth’ from the global pools of wealth it swims in?

Thiti Jamkajornkeiat: The protestors single out institutions that bear long history of royal investment, and hence, patronage. These institutions, in turn, have been helping to consolidate and reproduce the monarchical domination. Such royal patronage anoints the SCB Bank with the aura that makes it an “open-secret” member of the monarchical network. Though I am sure the protestors thought about the transnational circulation of money, their immediate objective was to expose the institutional foundation of this network monarchy and demonstrate the political dimension of these seemingly, or rather propagandized as, apolitical organizational bodies. When we conceive of the SCB bank as one node symbolically interchangeable with other nodes in the same royalist circuit—for example, the Siam Cement Group (SCG) or Deves Insurance—which, in turn, can serve as the rally’s strategic meeting point, then I think this targeting already fulfills the purposes.

I understand the coup against Thaksin as less about the capital flight from the sakdina, as they are players in the same capitalist field, than the eradication of an emerging hegemony that succeeded in rebuilding Thailand in the aftermath of the 1997 financial crisis—one that can build a better consensus between new economic elites, technocrats, and the working, especially regional, masses.

(Protesters standing at Bangkok’s Democracy Monument demanding the freedom of jailed organizers. Photo Credit: Prachatai)

(Protesters standing at Bangkok’s Democracy Monument demanding the freedom of jailed organizers. Photo Credit: Prachatai)

Asia Art Tours: Within any mass movement there are disagreements. For Thailand, one recent example has been Thailand’s liberals reacting negatively to Free Youth one of the largest organizing bodies in the protests, releasing a logo in homage to Soviet Communism’s ‘Hammer and Sickle” along with a statement advocating for Communist/Anti-Capitalist ideology to have a larger role in Thailand’s protests.

Could you discuss how these debates and tensions have played out so far on the ground between liberal and left elements in Thailand’s Protests? And what insights do you have (either from the present or historically) on if these tensions can be overcome?

Thiti Jamkajornkeiat: This is a challenging question to answer, given that Thailand, in my opinion, does not have longstanding leftist traditions. The Communist Party of Thailand was too “mechanical,” as many of its critics have already voiced up (too unsympathetically, in my opinion), and has long lost its influence, while budding Marxist groups on campuses lack a strong and unified organizational infrastructure. Trade unions have been usurped internally by reformists and sabotaged externally by the bourgeois state. With all these factors combined, I am quite confident to assess that in general, the class consciousness in Thai society is relatively low; instead, social inequality is understood through simple empiricist categories of rich and poor, Buddhist moralistic framework of bun-barami (accumulated good karma), but rarely in terms of class analysis. Without a shared class consciousness, which indeed requires a sustained organizing effort, it is difficult to unite migrant workers, indebted farmers, unemployable students, precarious white-collar, powerless gig workers, abused low-ranked police officers, underpaid affective labor, and many more together.

One identifier I see as unique to the current conflict is “pro-IX, anti-X” (ao kao mai-ao sip; เอาเก้าไม่เอาสิบ), meaning pro-Bhumibol, the previous king, but anti-Vajiralongkorn, the current king. They may join the current pro-democracy protests with a split personality. They may even support the monarchical reform as long as the protestors do not demand the abolition of the monarchical institution or republicanism.

(The symbol of “Restart Thailand”, a new movement launched by Free Youth. Photo Credit – Free Youth Facebook)

(The symbol of “Restart Thailand”, a new movement launched by Free Youth. Photo Credit – Free Youth Facebook)

Even liberal movements in Thailand, conceived as the main opposition to monarchism, again, in my opinion, were not as salient as one may think. I do not quite see political activities in Thailand that are so driven by ideologies and theories, as in the protestors have a preconceived understanding of their political orientation as liberal or socialist—and if so, what shades, what strands, or what lineages do we, Thais, understand these ideologies to be? The very last debate about Thai society as a totality between two “Marxists” Kasian Tejapira and Pichit Likhitkijsomboon dates back to the 1980s before the post-structuralist, culturalist, semi-liberal, and anti-communist analyses hijacked academia. We, Thais, are astoundingly impoverished when it comes to an understanding our own society and subjectivity.

What I rather want to say, again only in my view, is that in the midst of ideological deficiency, people realize their political orientation by positioning themselves within the current social contradiction, i.e., royalist / pro-military / authoritarian versus democratic. Then from there, they might further work out their ideological commitments. One identifier I see as unique to the current conflict is “pro-IX, anti-X” (ao kao mai-ao sip; เอาเก้าไม่เอาสิบ), meaning pro-Bhumibol, the previous king, but anti-Vajiralongkorn, the current king. They may join the current pro-democracy protests with a split personality. They may even support the monarchical reform as long as the protestors do not demand the abolition of the monarchical institution or republicanism.

Now, as to the tension between Thai leftists and liberals, I think it is more universal than could be contained by the ethnic or territorial marker Thai. I’d go as far as to say that those anti-communist reflexes to Free Youth’s hammer and sickle by who you identify as liberals are not actually liberal in any strict sense. It is not because they are prima facie liberal, then they are compelled to be anti-communist. I likewise call it a reflex because I understand this phenomenon as an automatic expression of Thais—“liberal” or otherwise—who have internalized the official hyper-royalist nationalist history. This official history is against any form of dissidence in nature, not to mention that it was perfected during the height of the Cold War’s anti-communist campaign.

If you ask me how this tension could be overcome in general, the logical answer would involve some sort of compromises like social democracy or democratic socialism, depending on which values you prioritize—or even anarchism, which is less concerned about the capitalist mechanism altogether. But should this tension be overcome is another question entirely. I have to admit that the pragmatist side in me would favor a strategic alliance between the two to attain the broadest popular front without actually resolving this tension. I do not want a world where capitalism continues to destroy our earth, exploit workers, and create social inequality after all.

I am quite confident to assess that in general, the class consciousness in Thai society is relatively low; instead, social inequality is understood through simple empiricist categories of rich and poor, Buddhist moralistic framework of bun-barami (accumulated good karma), but rarely in terms of class analysis. Without a shared class consciousness, which indeed requires a sustained organizing effort, it is difficult to unite migrant workers, indebted farmers, unemployable students, precarious white-collar, powerless gig workers, abused low-ranked police officers, underpaid affective labor, and many more together.

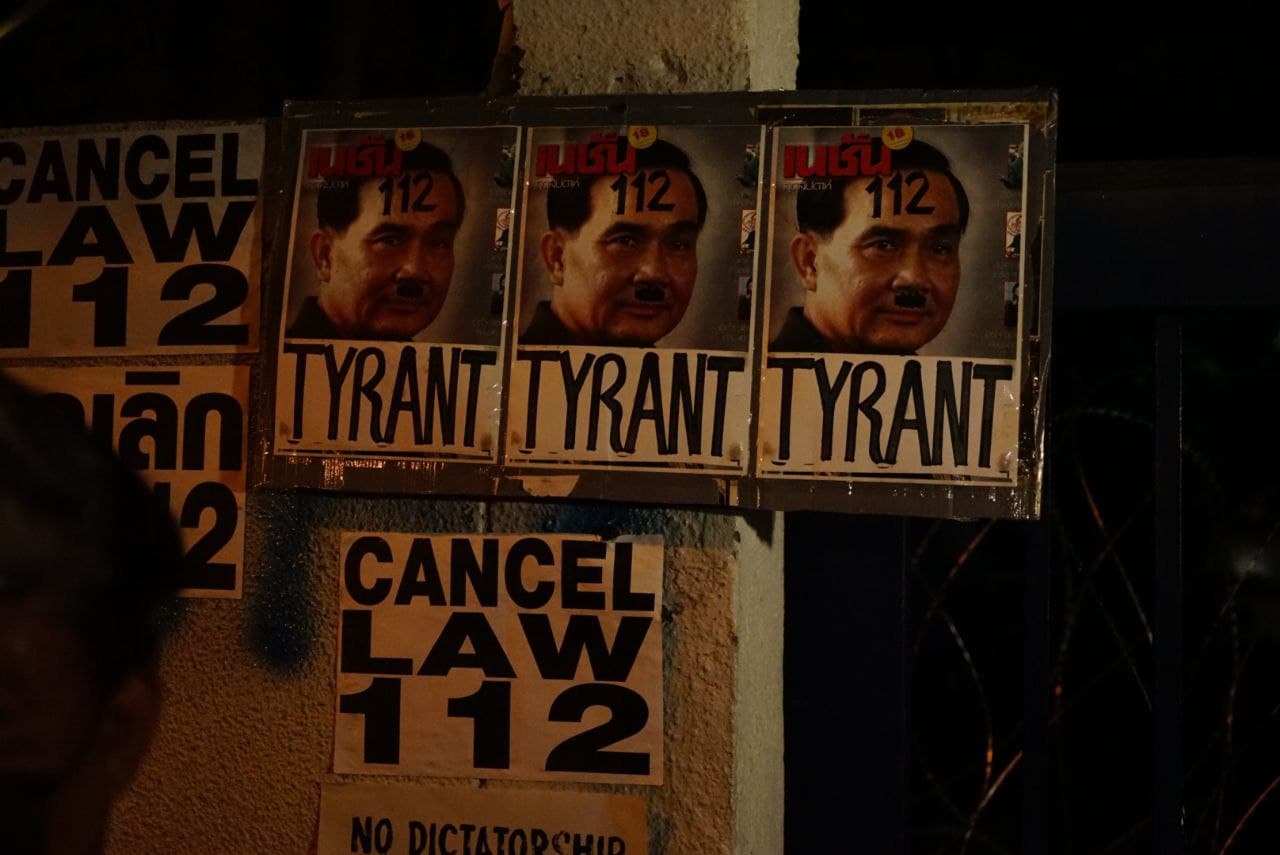

(Protest posters depicting the leader of the Military/Monarch Dictatorship in Thailand, Prayut Chan-o-Cha as Hitler. Photo Credit Prachatai)

(Protest posters depicting the leader of the Military/Monarch Dictatorship in Thailand, Prayut Chan-o-Cha as Hitler. Photo Credit Prachatai)

For more w. Thiti Jamkajornkeiat, you can read his wonderful essay on Spectre. Part 2 of our conversation can be found here.