This interview is with the Free Chen Guojiang Organization on arrested delivery driver / labor organizer Chen Guojiang also known by the nickname, Mengzhu (盟主).

We discuss Mengzhu, his life as a delivery driver, and his incredible organizing of China’s delivery workers. We then discuss why the Chinese government ordered his imprisonment, and why we need to organize to demand not only his release but justice for all gig economy workers.

Asia Art Tours: Right now in America, many reporters have published stories about horrible conditions in America’s ‘gig’ companies. Such as Uber workers sleeping in their car or Amazon workers having to urinate in water bottles or diapers. Why do workers at companies like MEITUAN or ELEME accept such horrible working conditions, and what terrible or terrifying stories do gig workers in China have about their workplaces?

Free Chen Guojiang: I would probably rephrase the question a bit before proceeding with my response. No, I don’t think delivery workers in China have ever accepted any of the horrible working conditions offered by Meituan and Ele.me, if by “accept” you meant they actually have a choice.

In China, if you do not have a college degree and do not have any particular skill-sets, and especially the case if you are from rural areas, then often you will end up in manufacturing factories or the construction sector. You are choosing between working in manufacturing factories/construction sector and working for gig economy platforms. Sadly enough, the working conditions, the wages and the social protections offered by manufacturing factories/construction sector are no better than the ones provided by gig economy platforms. People are often choosing between two evils, and they often make a decision by becoming a delivery worker based on the “the lesser of two evils” principle. I definitely would not say that delivery workers have a choice in this case, or that they have ever accepted any of the horrible working conditions.

What happens in manufacturing factories in China? Income wise, manufacturing workers suffer from wage cuts, wage arrears, arbitrary deduction in payments, overtime work without overtime pay, and etc. Take Foxconn as an example, during seasons when production scales up, workers might have to work 100 hours overtime per month. And there are definitely more manufacturing factories that have much worse working conditions than Foxconn in China. For many workers, it is common that you have to stand or sit there for 10-12 hours a day, repeating the same physical movements hundreds of times, or even thousands of times. You are not allowed to talk or look at your phones, and in some factories you have to get permission to use restrooms. Everything is about efficiency, and you will be verbally abused if you slow down. Such working conditions result in damages both to workers’ physical health and mental health. Marx is at least right about the phenomena of alienation – once getting into the capitalist mode of production, you are alienated from your labor, your humanity, and your fellows. And it could be extremely unbearable. What happens in the construction sector? Wage arrears is one of the biggest issues, and workers also suffer from workplace hazards such as dust inhalation that would result in permanent damage to their lungs and other work safety issues. Social protections are also not in place, and construction workers could work for months without getting paid at all.

Looking at CLB’s strike maps , it should also be obvious that delivery workers in China never ever accept the horrible working conditions. From January 2017 till May 2021, there have been 127 recorded strikes among food delivery workers across China.

(Videos of the labor organizer Mengzhu can be found on this channel. He tirelessly used live streaming and social media as part of his labor organizing)

You see that on the one hand we have the unbearable exploitative manufacturing factories/construction sector, and on the other hand we have food delivery platforms. Both sides are evil in terms of wage and working conditions, but for many, at least there seems to be more “freedom” and “flexibility” on the side of food delivery. Whether such appearances of “freedom” and “flexibility”are illusory is another thing. Mengzhu once said: “all we want in this life is nothing but freedom. We work hard and desperately earn as much money as possible – all of these are for our ultimate freedom. Compared to working in factories, working as a delivery worker grants me more spiritual freedom”. Also, when platform capitalism first started, it was true that delivery workers were paid relatively better than factory workers.

Looking at CLB’s strike maps , it should also be obvious that delivery workers in China never ever accept the horrible working conditions. From January 2017 till May 2021, there have been 127 recorded strikes among food delivery workers across China. Delivery workers in China have been striking for different reasons, mostly focusing on wage cuts and wage arrears. In January 2021, a delivery worker in Taizhou who worked for a third-party company delivering orders for Ele.me set himself on fire to protest the unpaid wages. He tried several times before he set himself alight, demanding a 5000 Yuan payment ($770), but never received any proper response from his boss. Luckily enough, he survived, but he will need another 1 million Yuan (155 thousand USD) for subsequent debridement surgeries. Who is going to pay for all of these surgeries?

Borrowing descriptions from the famous Renwu article: ‘Delivery Workers, Trapped in the System‘, delivery workers in China are trapped in a rigged system – though Mengzhu disagrees, he explicitly said that they are trapped in the platforms. With their income being squeezed, delivery workers in China are forced to work overtime. In December 2020, a delivery worker collapsed and died while delivering orders in Beijing. What’s ridiculous about Ele.me is that, because this delivery worker worked for a third-party crowdsourcing company to deliver for Ele.me, Ele.me initially was only willing to provide 2000 Yuan ($310) to the delivery worker’s family, in the name of compassion. People then started to find out that delivery workers have to pay 3 Yuan ($0.46) per day to the platforms, and within which only 1.06 goes to insurance – the rest all goes to the platforms. Great, gig economy companies not only refuse to cover their workers’ social protections, they even try to make money from their workers in the name of social protections.

In addition to wage cuts and wage arrears, delivery workers in China are also forced to take shortcuts/speeding to meet the short delivery time window, or they will be fined heavily by the company. As a result, work safety becomes a huge problem as well. Here is some data from the Renwu article, and it is kind of out-of-date now, “[in] the first half of 2017, there was a delivery rider casualty roughly every two days, according to data from the Shanghai Public Security Bureau’s Traffic Police. In the same year, 12 delivery riders were a casualty of traffic accidents every quarter in Shenzhen. In 2018, Chengdu’s Traffic Police reported less than 10,000 traffic violations by delivery riders, 196 traffic accidents, and 155 casualties.

(Workers in the EU holding a poster in solidarity for Mengzhu. Photo Credit: LEFT ECHO)

(Workers in the EU holding a poster in solidarity for Mengzhu. Photo Credit: LEFT ECHO)

Asia Art Tours: Reporters like Lauren Kaori Gurley and Professors like Eli Friedman have noted that in the US and China, Nationalism is used to win the respect and loyalty of workers to the state. I think that for workers to win, nationalism has to lose. Would Mengzhu (and your group) agree with this perspective?

Free Chen Guojiang: I can’t speak for Mengzhu since I don’t know him personally. Based on all of the videos he uploaded and all of the interviews he conducted, I would say that Mengzhu has not publicly talked about any of his political stance or his view on state propaganda, and I don’t remember him mentioning anything related to the resurgence of nationalism in China. I also can’t speak for my fellows in the solidarity campaign either since we haven’t yet explicitly discussed anything related to nationalism.

Speaking for myself, yes I agree with you – though there seems to be different forms of nationalism with different focus in today’s China. I always find nationalism to be oppressive in nature. It calls on an illusory unity and consensus at the cost of the marginalized and the oppressed. Nationalism in the context of today’s China is often closely related to terms such as “China Dream” and “China Speed”. It’s in the name of nationalism that you see feminist activists being silenced in China, it’s in the name of nationalism that you see NGOs being harassed in China, and it’s in the name of nationalism that you see rural migrants being classified as “underclass” and evicted from their homes in Beijing in December. It shouldn’t be surprising to anyone that the so-called “China Speed” and “China Dream” are also achieved at the cost of the welfare of the working class.

I don’t have any empirical data on what workers in China generally take their relationship with nationalism to be. An interesting example would be the Chinese workers in the documentary American Factory.

Sadly enough, the working conditions, the wages and the social protections offered by manufacturing factories/construction sector are no better than the ones provided by gig economy platforms. People are often choosing between two evils, and they often make a decision by becoming a delivery worker based on the “the lesser of two evils” principle.

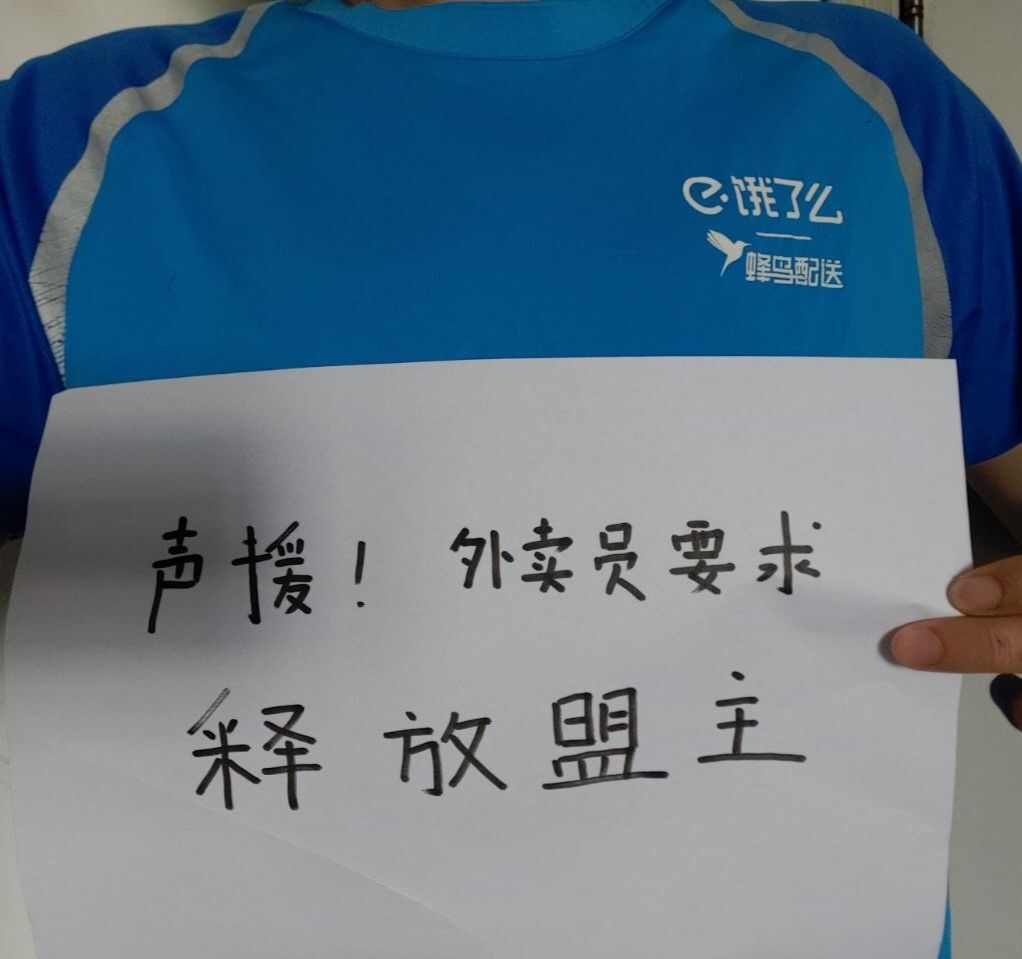

(An anonymous 餓了麽 worker holding a sign demanding Mengzhu’s release. Photo Credit: ELI FRIEDMAN)

(An anonymous 餓了麽 worker holding a sign demanding Mengzhu’s release. Photo Credit: ELI FRIEDMAN)

Asia Art Tours: How does Mengzhu want to transform the Gig Economy? And why did China’s government arrest him rather than support him?

Free Chen Guojiang: I am also curious whether the Chinese government has ever allowed any form of activists or self-organizations, especially during Xi’s era. “Stability preservation” or “stability maintenance” is at the core of many of the Chinese government’s decisions/policies, and self-organization like Mengzhu’s alliance would inevitably be seen as potentially distablizing. On the other hand, there have been some sugar-coated gestures recently by the Chinese government and gig economy companies, aiming to stabilize the delivery workforce, but you might think none of the measures put forth so far hit the core problem. You could also see that the Chinese government has started to promote another delivery worker who might be willing to collaborate with the government and join the shows.

Back to Mengzhu’s own effort and advocacy, I think his goals could be summarized as follows. Riders should be allowed to unionize and have a collective power when bargaining with platforms.Government should be responsible for introducing regulations and laws about platforms’ business models. Riders should receive proper training from platforms, including the popularization of basic legal knowledge. Also, Mengzhu also acknowledged the fact that many people only take delivery jobs as a temporary one, and hence the most urgent problems on the table are wage problems, not social protections – and you might think he is wrong about this part.

It’s in the name of nationalism that you see feminist activists being silenced in China, it’s in the name of nationalism that you see NGOs being harassed in China, and it’s in the name of nationalism that you see rural migrants being classified as “underclass” and evicted from their homes in Beijing in December

(Video of student organizers from the now suppressed and disbanded Jaisic Movement. Video Credit: JASIC WORKERS SUPPORT GROUP )

Asia Art Tours: Then compared to past labor organizers (Xiangzi, Jaisic, and so on) what traditional (or already attempted) methods of labor organizing did Mengzhu use? And what unique and new methods of labor organizing did he use?

Free Chen Guojiang:What’s special about delivery workers is that they are spatially isolated from each other, which might make it even more difficult for them to organize themselves. They have to be able to first connect with each other before any further collective actions. Mengzhu first created a Wechat group and then pasted a giant QR code advertising for his alliance on the back of his delivery tail box. When Mengzhu was on his way to deliver orders, other riders would have the opportunity to scan the QR code and join the Wechat groups. Soon, riders started to join Mengzhu’s wechat group and do the same by pasting a giant QR code on the back of their delivery tail boxes. By the time Mengzhu was arrested, the number of Mengzhu’s Wechat group had reached 16, covering more than 14000 riders. It’s really smart of him using QR code to build connections with other riders given the nature of their work.

Once the connection had been built, Mengzhu started to organize monthly dinners with delivery workers in Beijing, and such dinners were often sponsored by local businessmen. Mengzhu also offered space in his own house, aka “Riders’ Home”, to people who just came to Beijing and were looking for delivery jobs. He also managed to get in contact with a local law firm that was willing to provide free legal consults for delivery workers who might get into trouble and disputes.

(A video interview with Mengzhu conducted by the Southern Weekly. Video Credit: CAO NIMA)

Starting from March 2020, Mengzhu also started to make use of social media platforms, such as Weibo, Bilibili, and Douyin, to speak out on behalf of riders. He posted videos about how he managed to get his fellow delivery workers out of trouble, he posted videos of him publicly criticizing the platforms, he posted videos about rider safety, and of course you would also see videos about the monthly dinners and his interactions with the media.

I wouldn’t say that the use of Wechat groups or social media platforms are something unique to Mengzhu’s organizing techniques because it is simply not true. We have seen strikes among many other groups of workers in China organized via Wechat or social media platforms in recent years. But I would say that spatial isolation definitely makes Mengzhu’s organizing much more difficult, and it is really a smart move of him advertising his Wechat groups with giant QR codes.

Asia Art Tours: Mengzhu was willing to openly organize despite the dangers, this led to many more people (workers) discovering him. Could you explain why so many courageous people in China are willing to confront the government, despite the dangers? Why don’t they feel like they have another choice? And where did this courage (For Mengzhu and his worker comrades) come from?

Free Chen Guojiang: Well, I think it has to be analyzed case by case, and I don’t think I can provide any sweeping statement as to how and why there are so many courageous people in China who are still fighting for what they believe to be right.

In the case of Mengzhu, I actually don’t think he had a very clear idea about what kind of danger he might be facing when he first started his mutual aid networks and spoke out against the exploitation of delivery workers. Did he know that he was ultimately confronting the government when he started his mutual aid networks? I doubt so. And this is precisely what’s so heartbroken here: many ordinary people in China are willing to take actions to help others or speak out against exploitation/corruption/the lack of transparency, and they might just start with some small steps. Ironically, the lines are arbitrarily everywhere, and you never know when you are crossing the lines when doing something you mistakenly take to be perfectly normal or safe.

Mengzhu first created a Wechat group and then pasted a giant QR code advertising for his alliance on the back of his delivery tail box. When Mengzhu was on his way to deliver orders, other riders would have the opportunity to scan the QR code and join the Wechat groups. Soon, riders started to join Mengzhu’s wechat group and do the same by pasting a giant QR code on the back of their delivery tail boxes. By the time Mengzhu was arrested, the number of Mengzhu’s Wechat group had reached 16, covering more than 14000 riders

(A banner made by international solidarity groups demanding Mengzhu’s release. Photo Credit: FORUM ARBEITSWELTEN)

(A banner made by international solidarity groups demanding Mengzhu’s release. Photo Credit: FORUM ARBEITSWELTEN)

Mengzhu firmly believes in the importance of human connection. He was involved in a car accident when he started to deliver for platforms in 2018, and was hospitalized. He was there alone lying on his bed because he didn’t want to notify his family and let them worry about him. Meanwhile, the platforms started their wage cuts, and riders who spoke out against the new policy were kicked out of the delivery station’s Wechat group. It’s then that Mengzhu started to think about the importance of making friends and building mutual aid networks among delivery workers who are inevitably spatially isolated from each other. Mengzhu was actually arrested once in October 2019 when he attempted to organize a strike against wage cuts. During many different interviews, Mengzhu repeatedly said that he was totally caught off guard when he was arrested, but he was also unapologetic about what he had done. He firmly believed that what he had done was not against the law. He even said once that when he first attempted to organize the strike in 2019, he was full of enthusiasm, and he thought he was about to do a big thing – and an absolutely right thing.

If you go through Mengzhu’s videos and interviews carefully and thoroughly, you will see that sometimes he also felt demoralized. He sometimes thought that what he had done could probably change nothing systematic, he nonetheless proceeded with his agenda. At the core of his agenda, he really just wants to improve the working condition of his fellows and build a network so that they could help each other when in need. He is very clear about the necessity of collective action or self-organization in fighting against the exploitation of delivery workers, and he is also very advocative about the injustice done to delivery workers. He complained about how delivery workers’ voices were barely heard, and hence he just started to upload videos on social media platforms criticizing the platforms and the lack of regulations. He simply just believed that it was the right thing to do to make himself heard and fight against the exploitation, and delivery workers had no choice but to organize themselves.

Mengzhu firmly believes in the importance of human connection. He was involved in a car accident when he started to deliver for platforms in 2018, and was hospitalized. He was there alone lying on his bed because he didn’t want to notify his family and let them worry about him. Meanwhile, the platforms started their wage cuts, and riders who spoke out against the new policy were kicked out of the delivery station’s Wechat group. It’s then that Mengzhu started to think about the importance of making friends and building mutual aid networks among delivery workers who are inevitably spatially isolated from each other.

( A idle ELE.ME bike. Photo Credit: WIKIPEDIA )

( A idle ELE.ME bike. Photo Credit: WIKIPEDIA )

For more on Mengzhu’s case and organizing efforts to free him, please follow Free Chen Guojiang on Twitter. Please also visit: deliveryworkers.github.io, for global solidarity with Mengzhu and global gig workers.