I spoke to environmental researcher Jack Jenkins Hill on his role setting up Dawei Art Studio and how Myanmar’s Military has declared war on nature.

Asia Art Tours: For those unfamiliar, could you explain the richness of Myanmar’s ecosystems? What are the flagship species (both flora and fauna)? And what is unique to Myanmar’s ecosystems compared to other neighboring countries?

Jack Jenkins Hill: Myanmar is a very ecologically and biologically diverse country. From snow-capped peaks in the foothills of the Himalayas in northern Kachin State to well vast tracts of mangrove forests, and island ecosystems in south. The country still has large tracts of primary forest, largely in ethnic territories, that support sizable population of Tigers, Tapirs, Pangolins, Asian Elephants – all of which are endangered or highly vulnerable. Many of these species have become critically endangered or extinct in neighboring countries, and as such Myanmar has received significant attention from conservationists.

While this kind of biodiversity that is often characterized by megafauna existing withing “key biodiversity areas” is emphasized by conservation organizations and government departments, what is often missed is the richness and importance of biodiversity from the perspective of indigenous and forest dependent communities. Indigenous communities across Myanmar manage over vast stretches of forest and biodiversity, and manage them according to their own needs and objectives.

Woman searches for bamboo and wild vegitables in Tanintharyi Township. PHOTO CREDIT: Jack Jenkins Hill

Woman searches for bamboo and wild vegitables in Tanintharyi Township. PHOTO CREDIT: Jack Jenkins Hill

For example, Karen communities in Tanintharyi Region in southern Myanmar have identified over 245 different herbal medicine species, 188 wild vegetable species, and 70 fish species within the forests in their territories. This is undeniably an enormous biodiversity that has been looked after by indigenous communities, but is so rarely recognized or talked about in conservation circles.

While this kind of biological diversity is often ignored by international conservation organizations, it is central to the protection and sustenance of forest landscapes, including the megafauna mentioned above. Communities across many of these terrains work hard to sustain this biodiversity, and have a deep understanding and knowledge of the interconnectedness of it – the sustenance of clean water and ecosystems for wild vegetables and medicines, for example maintains habitats for a much larger array of plant and animal lifeforms.

Asia Art Tours: Palm oil seems to be invisibilized by the global media as a driver of climate collapse. Could you explain Palm Oil’s impact on Myanmar’s ecosystems?

And how is the fascist violence of Myanmar’s Tatmadaw connected to “Palm Oil Capitalism”?

Jack Jenkins Hill: Palm oil concessions have had a pretty catastrophic impact on forests and biodiversity in Tanintharyi Region, as well as on local communities. Unlike Indonesia and Malaysia where palm oil expansion has been driven by a global demand for the commodity, Myanmar, despite the vast concessions that have been granted, hardly produces any palm oil, and continues to depend upon imports. Instead the driver for palm oil concessions has been the expansion of military control into Karen territories, and the accumulation of quick cash through the plunder and sale of old growth forests.

To give one example, one concession in Kawthaung District, operated by a Korean company and affiliate of the Korean Forest Service, was granted a concession that spanned over 100,000 acres in 2011. After ten years, the company had only planted around 100 acres with palm oil, but 16,000 acres had been logged out. This area was home to sixteen villages, nine of which were destroyed during the civil war, and is home to a vast expanse of old growth forest that provides habitats for a number of highly vulnerable species including tapirs, Malaysian sun bears and leopards – all of which have been compromised. This really illustrates the nature of the smash and grab resource economy within the context of prolonged conflict – they call it palm oil, but really it’s just pillaging.

World Environment Day in Lenya. PHOTO CREDIT: Jack Jenkins Hill

World Environment Day in Lenya. PHOTO CREDIT: Jack Jenkins Hill

So if we ask the question how is palm oil capitalism connected to fascist violence, well it really is fascist violence itself. Displacement of communities in these areas took place during the late 1990s and early 2000s when tens of thousands of Karen villages were forced to flee during military onslaughts. While some ran across the border into neighboring refugee camps, others moved into the forest, into cities, or into neighboring villages.

It was around this time, in 2009, that the military declared Tanintharyi Region the oil bowl of Burma and proceeded to grant a vast number of large concessions, primarily to military affiliated companies, dispossessing the communities who had already been displaced. Seen from this angle, palm oil concessions were the other side of the coin to militarized fascist violence, while one physically displaced communities, the other dispossessed them.

MAC Concession in Manorone, Bokpyin Township, Tanintharyi Region – Over 100,000 acres were granted, but only 100 acres were planted. PHOTO CREDIT: Jack Jenkins Hill

MAC Concession in Manorone, Bokpyin Township, Tanintharyi Region – Over 100,000 acres were granted, but only 100 acres were planted. PHOTO CREDIT: Jack Jenkins Hill

Asia Art Tours: In contrast, how are PDF/EAO forces creating sustainable alternatives to the death-drive extractivist capitalism of the Tatmadaw & their foreign enablers?

And are there specific examples of liberated spaces for ecological sustainability that PDF/EAO forces or indigenous communities have created or are fighting to create?

Jack Jenkins Hill: Yes, there are have been a lot of initiatives that have sought to create sustainable alternatives to both top-down conservation and military led extractivism. Many of these have been in place for generations, created, practiced and protected by indigenous communities asserting control over their ancestral territories. As a result of increasing threats from the Burmese military and various extractive projects, civil society groups and ethnic revolutionary organizations have also sought to support and protect these initiatives, blending indigenous ecological knowledge systems and practices, with the revolutionary objectives of self-determination and autonomy.

There are actually a lot of such areas across Myanmar, however few of them have been widely publicized. In the Eastern Nagaland (in northern Sagaing Region), for example, Mount Saramati is a sacred mountain of the Makury Naga people, and has been protected by communities and tribal authorities for generations. Likewise Rvwangmong, the ancestral territories of the Rvwang people in Putao in northern Kachin State, as been conserved by local communities and indigenous institutions for generations – and is an area that in recent years has come under increasing pressures from mining, protected areas and crony tourism operations – pressures that communities have vehemently resisted.

Communities protect their forest in Lenya, Bokpyin. PHOTO CREDIT: Jack Jenkins Hill

Communities protect their forest in Lenya, Bokpyin. PHOTO CREDIT: Jack Jenkins Hill

In Tanintharyi Region the Landscape of Life represents a network of indigenous Karen territories placed along the Tenasserim River that communities have carefully been protecting from an onslaught of dams, mines, and plantations. Within these territories can be found vast diversity of flora and fauna. Finally, possibly the most well-known of these indigenous conserved territories is the Salween Peace Park, an initiative which has transformed 1.4 million acres of liberated Karen territory into a community governed conservation area. The Park is an example of bottom-up peace in a territory which has known over 70 years of war.

These models pose alternatives not only to the conservation and ecological practice, but also political imaginaries, systems and futures. The establishment of these areas includes the creation of new institutions, and the liberation of people and space from old ones, the reconfiguration of social and ecological relations, and collective creation and commitment to new values and ideas. In this way we can see these alternative forms of ‘conservation’ as being a revolutionary practice.

Fishing communities in the Myeik Archipeligo, Tanintharyi Region. PHOTO CREDIT: Jack Jenkins Hill

Fishing communities in the Myeik Archipeligo, Tanintharyi Region. PHOTO CREDIT: Jack Jenkins Hill

Asia Art Tours: How can an average reader help the Myanmar ecosystems and peoples struggling to survive the Tatmadaw? How can we build symbiosis and solidarity even if we’re outside the country?

Jack Jenkins Hill: The biggest threat facing Myanmar’s ecosystems and people is the Burmese military, who have been rapidly deforesting the country to generate more funds for their fascist war and occupation. Recent data has shown that the military has made over $190 million in timber exports since the February 2021 coup alone, with $37 million of these from states that have already imposed sanctions. During this time the military killed over 1,700 people, it has launched ariel attacks against civilian targets, it has burned entire villages, its displaced over 440,000 people.

When we are looking at different modes of international solidarity, we have to remember that fascism is always interconnected through bonds of solidarity too. Fascism in Myanmar is connected to fascism everywhere, it is an ideology that feeds off material solidarity between tyrants, capitalists, cronies across the globe. We can see this manifest in arms sales from one despot to another, another example perhaps are are the super yachts of fascist dictators, capitalists and oligarchs, whose assets that have been acquired through violence and exploitation, and are often adorned in Myanmar blood teak. These need to be seized, destroyed, sunk, burnt.

We can therefore understand that resistance to fascism anywhere supports the struggle against fascism everywhere – the liberation of people in Myanmar is a major victory for the fight against fascism globally. We need to find the points of connection that breathe oxygen into fascism and the networks that sustain it, and we need to join together in solidarity to destroy them. This means supporting workers unions, consumer boycotts, indigenous sovereignty, anti-arms trade campaigns and climate justice struggles – these fights are all interconnected.

Struggling from the Hell by Moh Moh. PHOTO CREDIT: Jack Jenkins Hill

Struggling from the Hell by Moh Moh. PHOTO CREDIT: Jack Jenkins Hill

Asia Art Tours : Prior to the Tatmadaw’s coup, what was the art scene like in Myanmar? And what role did the Dawei Art Space see for itself?

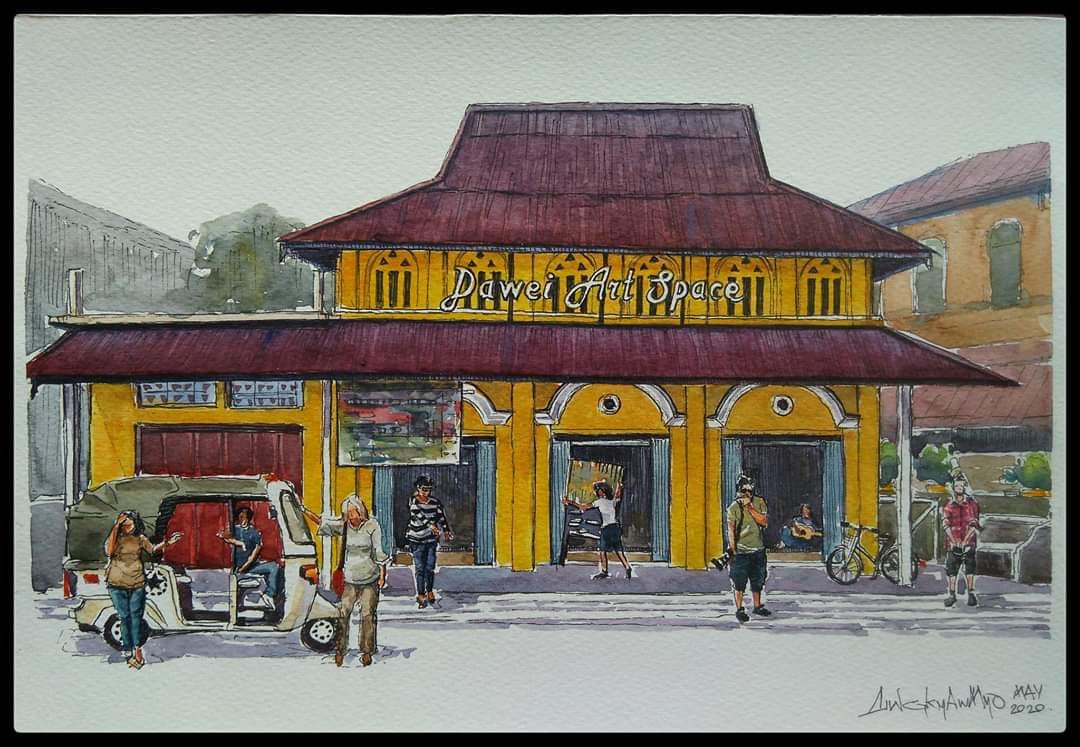

Jack Jenkins Hill:A few friends and I got involved in starting the Dawei Art Space in 2019 because there was a need to have an open, public and creative space in southern Myanmar. Dawei had become, as it always had been perhaps, a site of great interest from those on the outside – the area became awash with new oil palm plantations, mining projects, mega-industrial zones, and huge conservation areas. A strong network of civil society groups and activists emerged from across southern Myanmar, who fought and campaigned, often with success, against this barrage of exploitative and extractive interest in the region.

The Dawei Art Space was intended to be a space for creating or expanding political imaginations for something different. In the space we hosted exhibitions, workshops, public talks, music events, poetry evenings, theatre, and often it was a space for people, often youth, to spend time, talk, organize. We wanted to create an art space that wasn’t for artists per-se, but was for everyone to come and engage in different creative processes. I think we were successful in doing this. The space received a really great response – there were a lot of events, and a lot of people would come

I’m not sure exactly how the space fit into the art scene in Myanmar at the time – the art scene over the past ten years had flourished, a lot of contemporary artists had received greater recognition, the easing of censorship restrictions during that period had also led to an emergence of art and artists that could be more overtly political and had more opportunities to develop and strengthen their practice. This was a really important and exciting time. This renaissance, if we can call it that, however was largely concentrated in Yangon, with few spaces and opportunities opening up in other towns and cities, especially in ethnic areas. We also wanted to bring some of this energy and creativity to Dawei.

Dawei Art Space. PHOTO CREDIT: Jack Jenkins Hill

Dawei Art Space. PHOTO CREDIT: Jack Jenkins Hill

Asia Art Tours: Post-coup, how are artists supporting themselves under the current junta occupation? And how are they using art to contribute to the revolution (both for EAOs as well as the PDF)?

Jack Jenkins Hill: Since the coup, the Dawei Art Space was temporarily forced to close, and Myanmar is no longer a safe place for artists and activists. The military view creativity, imagination and those with alternative ideas and visions as an existential threat and are trying with all their might to destroy it. Many artists have been arrested or killed, some have fled either to liberated areas or to neighboring countries, and others have had to be covert about their work, using pseudonyms and avoiding public attention. Despite this, art has become ubiquitous since the start of the revolution. Many people are producing art works, even those who hadn’t done so before. For many this is an act of resistance, solidarity, a process of documenting and reflecting on the unfolding events, or for processing and dealing with traumas.

There have been some artists, such as Rap Against Junta, for example, who have been using their music as an act of resistance and defiance, using hip-hop as a creative means of bringing justice and unity, and establishing new platforms for the revolution. Other artists and collaborations have used art as a means of forging national and international solidarity, Raise Three Fingers, a collaboration of several different initiatives, for example have collected art works of solidarity from Myanmar and across the globe. Other artists are using their art works for mutual aid, selling paintings and using the proceeds to raise funds for IDPs, CDM workers and those who are fighting the revolution. Federal Art Space or Art for Solidarity is one example of this, but there are many more.

No Title by Shwe Thinn Moe. PHOTO CREDIT: Jack Jenkins Hill

No Title by Shwe Thinn Moe. PHOTO CREDIT: Jack Jenkins Hill

During the revolution, I think that art holds a central role in resistance to the junta, reimagining a new nation(s), and as modes of material and symbolic solidarity with others who are suffering. In this way art is a central tool of the revolution. I really hope that those on the outside will reciprocate this solidarity and continue supporting and engaging in art and creative practices in Myanmar – it is times like this where art is at its greatest importance, at its most revolutionary, and at its greatest risk.

The continuation of art, creativity and imagination is a symbol that the revolution is alive. I am not in a position to speak in greater depth on this, but it would be really great to provide more platforms to Myanmar artists to talk about their practices, struggles, and the role of art in this time of revolution.

Dawei Art Space by Aung Kyaw Myo. PHOTO CREDIT: Jack Jenkins Hill

Dawei Art Space by Aung Kyaw Myo. PHOTO CREDIT: Jack Jenkins Hill