I spoke to Myanmar Evictions Watch, who document the violent and illegal evictions overseen by Myanmar’s military dictatorship.

What follows is a comprehensive exploration of authoritarianism, capitalism, and property in Myanmar.

Asia Art Tours For the past three years I’ve closely observed global protests but your group is the first I’ve seen based around evictions. In the wake of the Tatmadaw’s coup attempt, could you discuss how the group came together, and why you decided to focus specifically on evictions?

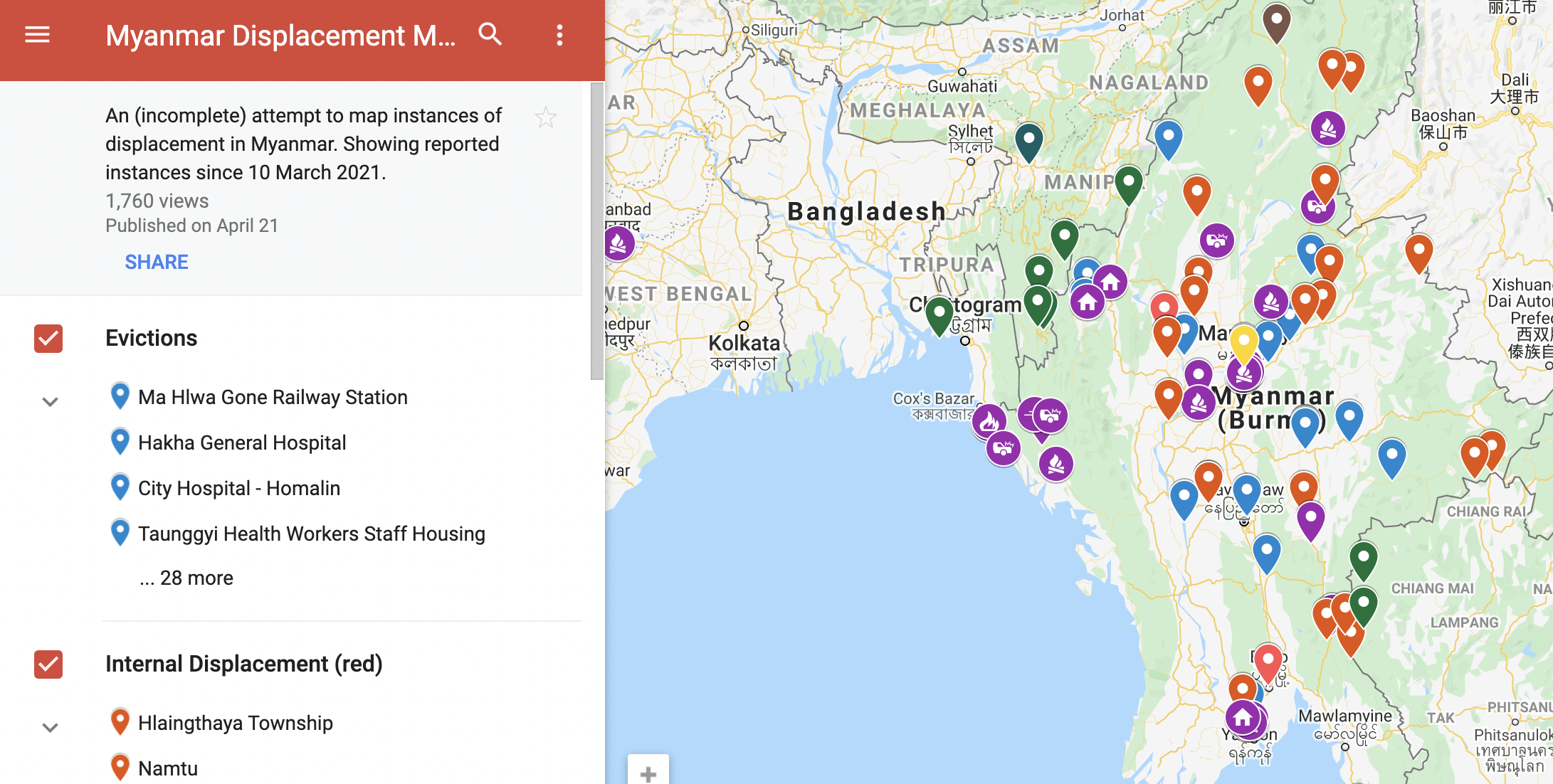

Myanmar Eviction Watch:Myanmar Evictions Watch is a collective that came together with the minimum objective of recording and keeping a public archive of instances of forced evictions and displacement in the light of the military coup. As the current coup unfolded, several of us were reminded of previous coups and the history of large-scale forced evictions that came in its wake, particularly in, but not restricted to, the city of Yangon. We decided to come together soon after the forced evictions of more than 1000 railway workers participating in the Civil Disobedience Movement (CDM) at the Ma Hlwa Gone railway staff housing quarters, an incident that received global attention including a statement by a group of UN human rights experts.

Forced evictions are a point of entry for us to investigate how the Myanmar military’s (or sit-tat) power operates, reproduces, and manifests itself in space, particularly in urban Myanmar. We can think of three modes through which the military controls urban space:first, as mentioned earlier, forced evictions have been repeatedly used as a way of controlling urban space (and through it, the people), most devastatingly, after the protests of 1988 when over 500,000 people were forcefully resettled in the periphery of Yangon where new townships were made without any sufficient infrastructure. This operation was so massive, targeting, among others, those who were classified as “squatters” and civil servants, that the total land area under the control of the administration in Yangon had to be increased by 77%. Several townships that are at the vanguard of the resistance in Yangon- Hlaing Thar Yar, North Okkalappa, South Dagon- were all created after previous coups.

Second, the military owns or controls vast amounts of land in almost all major Myanmar cities. The largest of these tracts of land are often in the form of encampments, training centres, and military bases. One of our projects aims to map direct ownership and use of land by the sit-tat in major Myanmar cities. Our research reveals that in the city of Taunggyi in Shan State, for instance, about 12.8% of the total land area of the city is owned or classified for use by the sit-tat. In the city of Kalaw, this goes up to 20.5% due to the large institutional presence of the military there. The outsized presence of the military in Myanmar’s cities plays a central part in their ability to mobilize the troops and manage the logistics of the brutal crackdown and killing we are seeing on a daily basis.

Third, as groups such as Justice for Myanmar have effectively shown, land and real estate speculation remains a key mode of revenue mobilization and profit making for the sit-tat. The political power of the military cannot be curtailed without understanding its relationship with land and severing it from the land it controls. We hope to undertake more collective work on all three fronts.

Additionally, the current political moment in Myanmar has spurred several ongoing conversations about justice. As a collective, we recognize that justice necessarily has a “spatial” element. For example, how will the solidarity being expressed across ethnic lines translate into material improvements, for instance, housing, land, and property restitution for Rohingya who wish to return home ? How can the kind of democracy being envisioned address the great inequality in ownership of land in Myanmar? What does spatial justice mean to the thousands of working-class citizens in Yangon’s periphery? We hope to remain engaged in critical conversations on these questions.

land and real estate speculation remains a key mode of revenue mobilization and profit making for the sit-tat. The political power of the military cannot be curtailed without understanding its relationship with land and severing it from the land it controls.

Screen Shot of the Myanmar Evictions Project Map which can be viewed in full here

Asia Art Tours: The Hong Kong publication Lausan has done incredible work documenting how colonial and modern influence from the US & UK have shaped Hong Kong’s Police. I know you cannot give a comprehensive answer, but in brief how have colonial or foreign powers educated or influenced the Tatmadaw’s own violent techniques & technologies?

Myanmar Eviction Watch: We are certainly not experts on this and will limit our answer to how colonial practices still define the use of forced evictions as a technique of war in Myanmar. Scholars have documented the sit-tat’s Pyat Lay Pyat or Four Cuts policy (cutting people off from food, funds, intelligence, and recruits) used first against the Karen population in the late 1960s. The adoption of the Four Cuts policy was inspired by the British campaign against the communists in Malaya which used similar tactics to brutal effect. Forcible resettlement played a key role in the Malayan emergency so much so that the period between 1948 and 1960 saw the creation of 600 “new villages”, constructed largely as resettlement sites for forcibly evicted Malaysian Chinese. It is estimated that about 575,000 people (deemed “squatters”) were relocated to these resettlement sites. It remains no coincidence that the displacement of civilian populations remains a characteristic feature of the military’s operations against ethnic nationalities in Myanmar. Forcible displacement is not a by-product or “collateral damage” of the sit-tat’s operations. Instead, it must be seen as a central tactic of the operation itself. We saw this being used most violently in the repeated expulsion of the Rohingya population from Rakhine State.

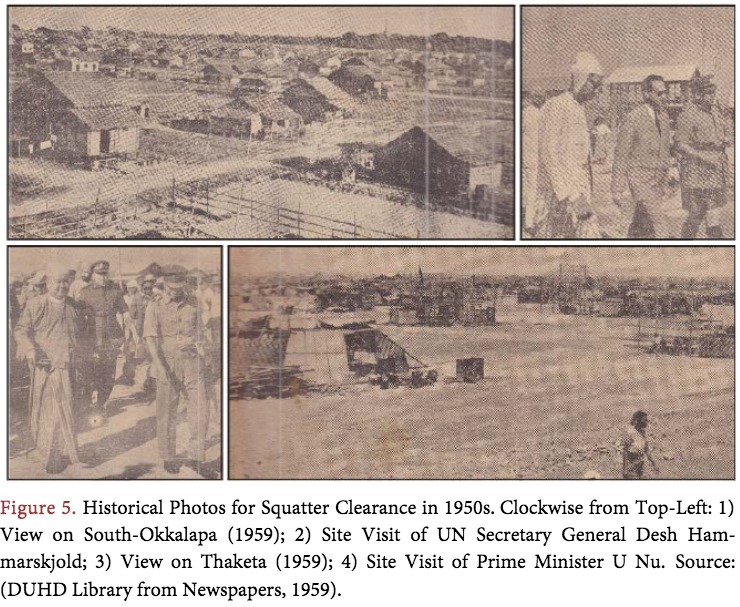

In urban areas of Myanmar, particularly Yangon, the history of forced evictions is inseparable from the history of the city itself. Forced evictions have remained the central paradigm of urban planning in Myanmar. As scholars have noted, there has been a remarkable coherence in terms of urban planning and housing policies across the regimes that have ruled Myanmar since colonial times. The creation of Rangoon was contingent on the erasure of all pre-colonial rights or claims on land. Rangoon then developed through successive waves of forced displacement of the urban poor, whether after the 1958 military caretaker government or the post 1988 forced evictions. For the military junta, a central objective of this transformation of the city through evictions was to make the city more immune to insurrections and protests. In 1988, for instance, residential areas in Bahan township near the Shwedagon Pagoda, where residents provided material support to protestors, were particularly targeted for forced evictions and later, redevelopment.

We want to clarify here that the use of forced evictions as a preferred mode of planning is not restricted to military-run administrations. As recently as 2016, the former NLD Chief Minister of Yangon, Phyo Min Thein announced a plan to relocate “squatters” in Yangon. The image of the “squatter”, a colonial creation, looms large in urban discourses in Myanmar- it is repeatedly invoked to create a state of “displaceability” and denial of substantive citizenship rights. Even before the coup, fear of evictions was pervasive among communities.

The image of the “squatter”, a colonial creation, looms large in urban discourses in Myanmar- it is repeatedly invoked to create a state of “displaceability” and denial of substantive citizenship rights. Even before the coup, fear of evictions was pervasive among communities.

Residents of Hliang Thar Yar whose homes were eventually demolished by the military. Photo Credit: MYANMAR EVICTIONS WATCH

Residents of Hliang Thar Yar whose homes were eventually demolished by the military. Photo Credit: MYANMAR EVICTIONS WATCH

Asia Art Tours: Turning to the focus of your group, could you discuss the scope and scale of evictions taking place against Myanmar’s CDM protesters? (How many? How widespread?) And could you explain what makes someone a target for potential eviction?

Myanmar Evictions Watch: Before we answer the specific question, it is important to understand the landscape of displacement in Myanmar before February 1, 2021. Already, about half a million people, primarily those who fled conflict in Rakhine/Chin, Kachin, Shan, and Karen States, were internally displaced, sheltering either in camps or what are referred to as host communities. This figure includes the 125,000 Rohingya who have been confined to camps since 2012 in Rakhine State. Added to this, job losses due to the economic downturn caused by COVID-19 had precipitated the housing crisis in Myanmar’s major cities- several thousands in informal settlements were under heightened threat of evictions as were workers who found it difficult to pay rent on their dormitories or workers’ hostels.

Since the coup, we have seen the sit-tat and police unleash a campaign of terror on residential neighborhoods in Myanmar’s cities. This has meant the nightly terrorizing of residential neighborhoods, midnight raids, indiscriminate shooting into homes, arson, and looting of civilian property. Six year old Khin Myo Chit was shot dead in her home, in her father’s arms in Mandalay during a raid and search on her home. In addition, a law of colonial provenance requiring the registration of overnight guests (repealed in 2016) was amended to allow for warrantless inspection of homes and allied fines/imprisonment for failure to register overnight guests. The Law Protecting the Privacy and Security of Citizens (2017) required the presence of two witnesses during a search of a home; this too has been dispensed with. All this to say that deliberate targeting of homes has been widely employed by the security forces with impunity.

We have recorded, since March 2021, close to 40 incidents where civil servants participating in CDM have been evicted from their housing. We are certain that there are more cases but we haven’t been able to verify more due to the internet blackout and in some cases, lack of reliable sources. The question of how many people were evicted is even harder to answer; we don’t have an accurate estimate. Our conservative estimate, from the incidents that we have been able to confirm, is that at least 7,500 people (including family members) have been evicted for their participation in CDM. The numbers are likely more. We have recorded cases of forced evictions spread across 11 different states/regions (Yangon, Mandalay, Chin, Bago, Shan, Mon, Magway, Sagaing, and Bago). We are a small collective trying to do our best, so we are certain we have missed out on recording more instances of forced evictions.

Although we have also attempted to record and map people fleeing either direct violence or the threat of violence by the security forces, we must say that this exercise is rife with methodological problems and possible errors. The most widely cited figures on displacement are those provided by UN agencies. The latest estimate from UN OCHA, for instance, estimates that there have been 230,000 IDPs since the coup. However, we believe that the numbers are substantially higher, our conservative estimate is that about 500,000 people have had reason to leave their habitual place of residence since the coup. Of course, many have returned to their residences and aren’t IDPs at the moment, we have lesser accuracy on return than we do on displacement. These include large number of residents fleeing from townships under martial law like the 100,000 residents who fled Hlaingtharyar (not considered IDPs by the UN), the large-scale movement of people from areas that have seen widespread violence (for example, 100,000 people fled the town of Bago during the violent crackdown there), internally displaced in Karen, Kachin, Chin, and Shan States due to the escalating conflict, and refugees who have fled to Thailand and India. If our estimates are right, this would mean a doubling of the number of displaced persons (over the pre-coup level).

Our conservative estimate, from the incidents that we have been able to confirm, is that at least 7,500 people (including family members) have been evicted for their participation in CDM. The numbers are likely more.

“In #Monywa, over 200 households from 4 wards fled from their home due to the shooting by the police. Some have gone back to their village, while some are sheltering at the monasteries. “ Credit: MYANMAR EVICTIONS WATCH.

Asia Art Tours: To center CDM protesters, for those who have been evicted (or are trying to avoid eviction) what networks of mutual aid or community support have emerged to allow them to continue participating as CDM protesters? And has the CDM engaged in direct actions against property owned by the Tatmadaw?

Myanmar Evictions Watch: This is a difficult question to answer primarily because CDM is a decentralized movement of several heterogeneous actors, moved to the movement for varied motivations. From what we have seen, evicted protestors are dependent on existing social networks, local civil society organizations, and parahita (voluntary) groups. Several evicted residents are sheltered temporarily in monasteries, churches, or large community halls belonging to one of these organizations. It is true that there are no alternate institutional structures that can offer safe refuge for protestors, at scale. This is an area that might require more sustained attention from the movement, especially given the rising numbers of displaced, targeted specifically for their participation in the movement. If the movement is to succeed in the long-term, the creation of these alternate institutions that can meet both immediate needs of evicted families ((food, accomodation) or those fleeing violence is critical. In some cases, we are aware of networks of self-organized groups active in CDM who have helped protestors to relocate to safer locations or safe houses.

We have also seen in recent days an escalation in the seizure and confiscation of property (including homes) of members of the NUG and those with links to the NLD. According to The Irrawaddy, about 100 properties have already been confiscated and indications are that more are likely to be targeted. We understand that these evictions and confiscations are under the Unlawful Associations Act, another law of colonial provenance that is being weaponized to curb dissent.

In addition, we have also seen an escalation in evictions of those referred to as “squatters” especially after Min Aung Hlaing’s visit to Yangon on October 8th. During his visit, as reported by Frontier Magazine, he spoke about the need to make Yangon “a green city and a clean city” and added that solving the “squatter problems” in Yangon can help beautify the city. Within a week, eviction notices were sent to residents of informal settlements in Hlaing Thayar. These evictions have been widely reported in the media such as DVB English News, BBC Burmese, Radio Free Asia, HTY Information, Myanmar Labour News. We understand that up to 20,000 people could have already been evicted but it is difficult to know the true numbers as photos, videos, and recordings of the evictions have been restricted. Although some of the evicted residents received some support from local volunteers and civil society groups, these networks are often fragile. In addition, support to evicted communities has been often restricted and cracked down by the Tadmadaw. For example, factory owners and hostel owners were ordered not to provide any rooms to evicted informal residents. Troops and police vehicles have been stationed around the sites of eviction so that no one can return or conduct any protests. Reports also indicate that those who planned to return to their native villages were “charged” about 40,000 kyats by military soldiers near the Pan Hlaing bridge. These are the very difficult conditions under which any network of mutual aid or community support operates.

If the (CDM) movement is to succeed in the long-term, the creation of these alternate institutions that can meet both immediate needs of evicted families ((food, accomodation) or those fleeing violence is critical.

“Residents along Irrawaddy river, #Mandalay were forced to flee their home by the military on 17th Nov. Some have been living there over the decades in this area. There is a plan to clear settlements along the river bank in MCDC zone tomorrow.“Photo & Caption Credit: MYANMAR EVICTIONS WATCH

“Residents along Irrawaddy river, #Mandalay were forced to flee their home by the military on 17th Nov. Some have been living there over the decades in this area. There is a plan to clear settlements along the river bank in MCDC zone tomorrow.“Photo & Caption Credit: MYANMAR EVICTIONS WATCH

Asia Art Tours: How have you seen class play an important role in those who do and do not support the CDM movement? And through your research do you believe that a solidarity can be built between the ‘renters’ and ‘landlords’ of Myanmar to unite against the Tatmadaw and build a new Myanmar?

Myanmar Evictions Watch: First, we think that it is important to clarify who the landlords or land owners are in Myanmar’s cities. As we pointed out earlier, the Myanmar military is possibly the largest landowner in several major cities in Myanmar, owning up to 20% of all land in some cases. There is also a series of opaque subletting and renting of public lands to those with links to the military, as exemplified by the case of Aung Pyae Sone (son of Min Aung Hlaing) who reportedly has a very lucrative contract from YCDC to run a restaurant at People’s Park. According to estimates from UN-Habitat, residents of informal settlements who make up approximately 10% of the city’s population occupy 1,822.31 acres or 7.37 square kilometres, approximately 1.23 % of the city’s total land area. In contrast, a back of the envelope calculation suggests that the 16 golf courses in Yangon take up 8-10 square kilometres of land. A recreational sport for the 0.1% occupies as much land as homes for the poorest 10%. We offer this comparison to suggest that unequal class relations are spatially encoded into the very structure of cities in Myanmar.

We witness today that this spatialized class structure is very much mirrored in the revolution, in the sense that these frontier spaces, the peripheries of the Yangon, have become strongholds of resistance. Low-income residents, factory workers, “squatters”, etc. have been among the most active participants in opposing the coup, not only through their support of the CDM movement but on every other front. We see this in the mobilization of Labour Unions, the organization of strikes, the participation in protests, the fact that these areas have offered hideouts to resistance members. The role of the marginalized in the ongoing resistance cannot be overstated and should not fall into oblivion once freedom is restored.

Second, your question reminded some of us of Thakin Po Hla Gyi’s revolutionary text Strike War, written during the Oil Strikes in 1938. In the version of the text translated into English by Stephen Campbell, Thakin Po Hla Gyi (or the Ogre) speaks about several forms of inequality that workers in Myanmar face including inequality in housing. To quote a lengthy passage, he writes:

“Among the lackeys and servants of the imperialists, the governor who is a respected person and the central chairperson has the opportunity to live in a personal mansion that is in actual fact about 100,000 square feet in area. As for the high court judges and deputy commissioners, managers, directors and senior and junior ministers, they similarly have the opportunity to reside in well furnished enclosures of about 50,000 square feet in area. As for the poor workers, they have lost their homes, become financially ruined and become fully impoverished. Some poor people, being homeless without as much as a seed’s weight in personal possessions, are living in the alleys between buildings and avoiding police patrols.

When they again rent a home with their monthly salary, since they cannot afford the rent, they must live in narrow 300 square-foot rooms that are so cramped with about 50 workers in each that there is no floor space on which to walk and there is not even enough room to roll over while you sleep. Although they may want to get up at night and go to the toilet, since there is no space to walk they worry about stepping on those who are sleeping and can barely restrain their bowels. In summary, although the imperialists, who comprise only about 0.1 per cent of the population of Burma, are able to engage in commercial enterprises valued at over 160,000,000,000 kyat, they only pay the poor, who comprise 95 per cent of the population, a daily wage of about 2 annas per person”

Those reading this passage for the first time may be struck by how accurate the description of the living conditions of the working classes has remained to this day. There has been an outpouring of solidarity and mutual aid in the wake of the coup and the Covid-19 crisis. For example, some landlords offered rooms to those who needed to escape or were evicted, or offered rent-free extensions because many renters could not afford to pay due to the joblessness. However, the question remains whether this is enough to offer structural solutions to the issue of class inequality? Our understanding is that the new Myanmar that will come when the revolution succeeds cannot escape the critical questions about capitalism that Thakin Po Hla Gyi posed in 1938.

Lastly, a contemporary of Thakin Po Hla Gyi from India, Dr B R Ambedkar, the Dalit leader widely considered to be the architect of India’s constitution summarized his disillusionment with the Constitution he helped create by saying that “democracy in India is only a top-dressing on an Indian soil which is essentially undemocratic.” In a warning to the Constituent Assembly he remarked:

“On the 26th of January 1950, we are going to enter into a life of contradictions. In politics we will have equality and in social and economic life we will have inequality. In politics we will be recognising the principle of one man one vote and one vote one value. In our social and economic life, we shall, by reason of our social and economic structure, continue to deny the principle of one man one value. How long shall we continue to live this life of contradictions? How long shall we continue to deny equality in our social and economic life? If we continue to deny it for long, we will do so only by putting our political democracy in peril. We must remove this contradiction at the earliest possible moment or else those who suffer from inequality will blow up the structure of political democracy which this Assembly has laboriously built up.”

In essence, the new Myanmar we would all like to see must think of political, social, and economic equality in tandem. A transformative constitution (on which there is a lot of focus) must be complemented by an equally transformative economic agenda.

A back of the envelope calculation suggests that the 16 golf courses in Yangon take up 8-10 square kilometres of land. A recreational sport for the 0.1% occupies as much land as homes for the poorest 10%. We offer this comparison to suggest that unequal class relations are spatially encoded into the very structure of cities in Myanmar.

Photo Credit: MYANMAR EVICTIONS WATCH

Photo Credit: MYANMAR EVICTIONS WATCH

For more on Myanmar Evictions Watch, check out: @EvictionsWatch