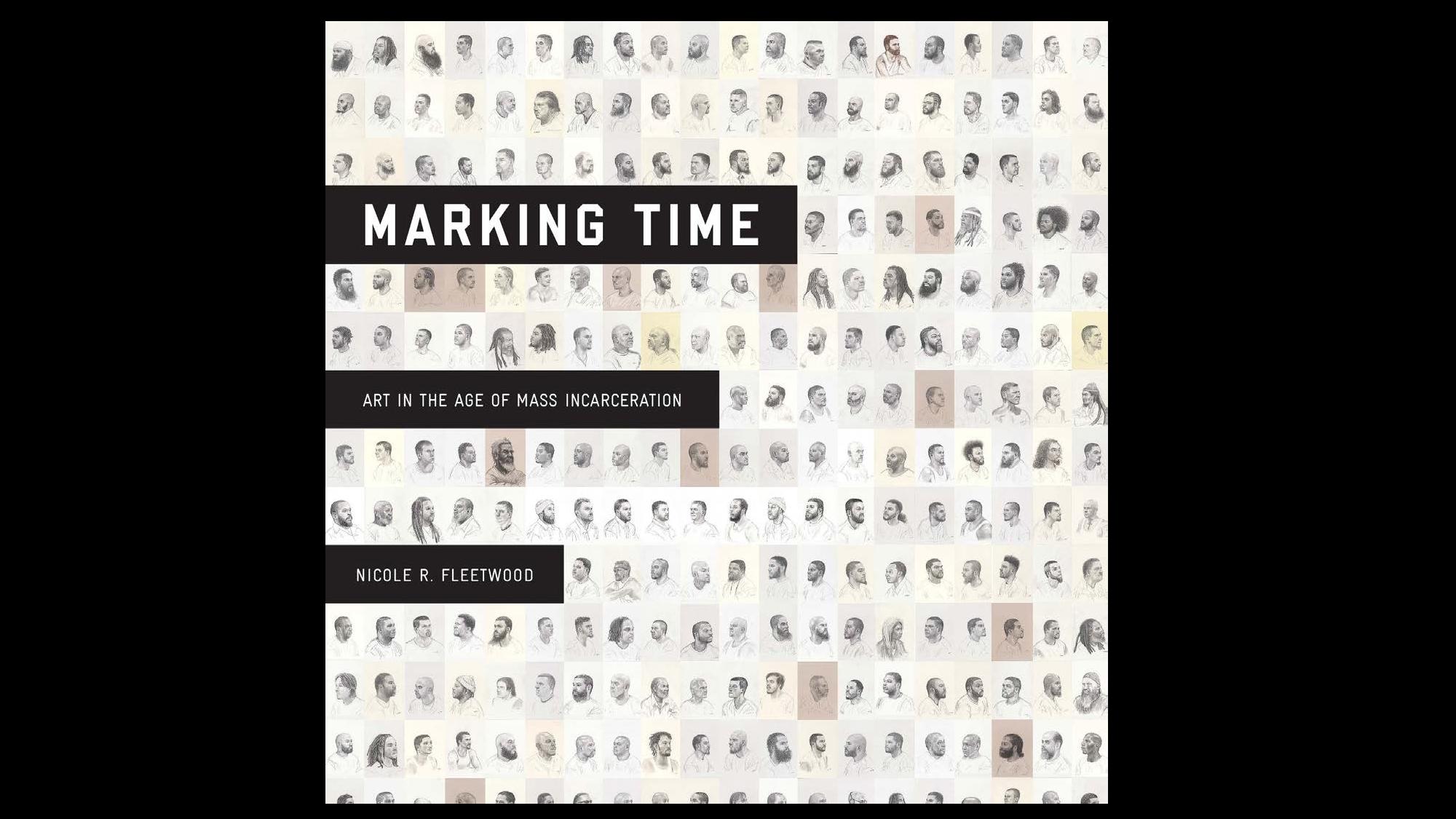

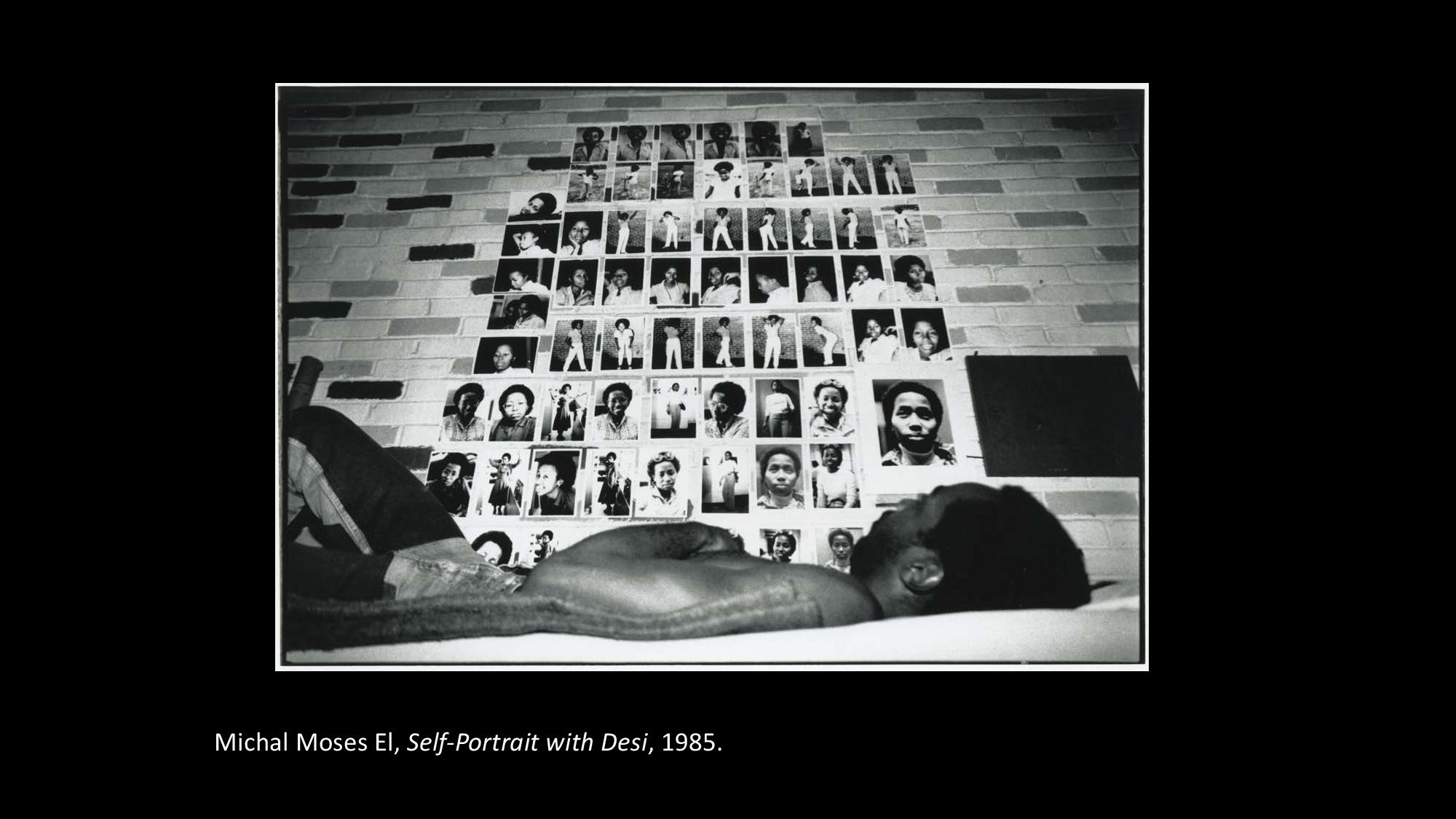

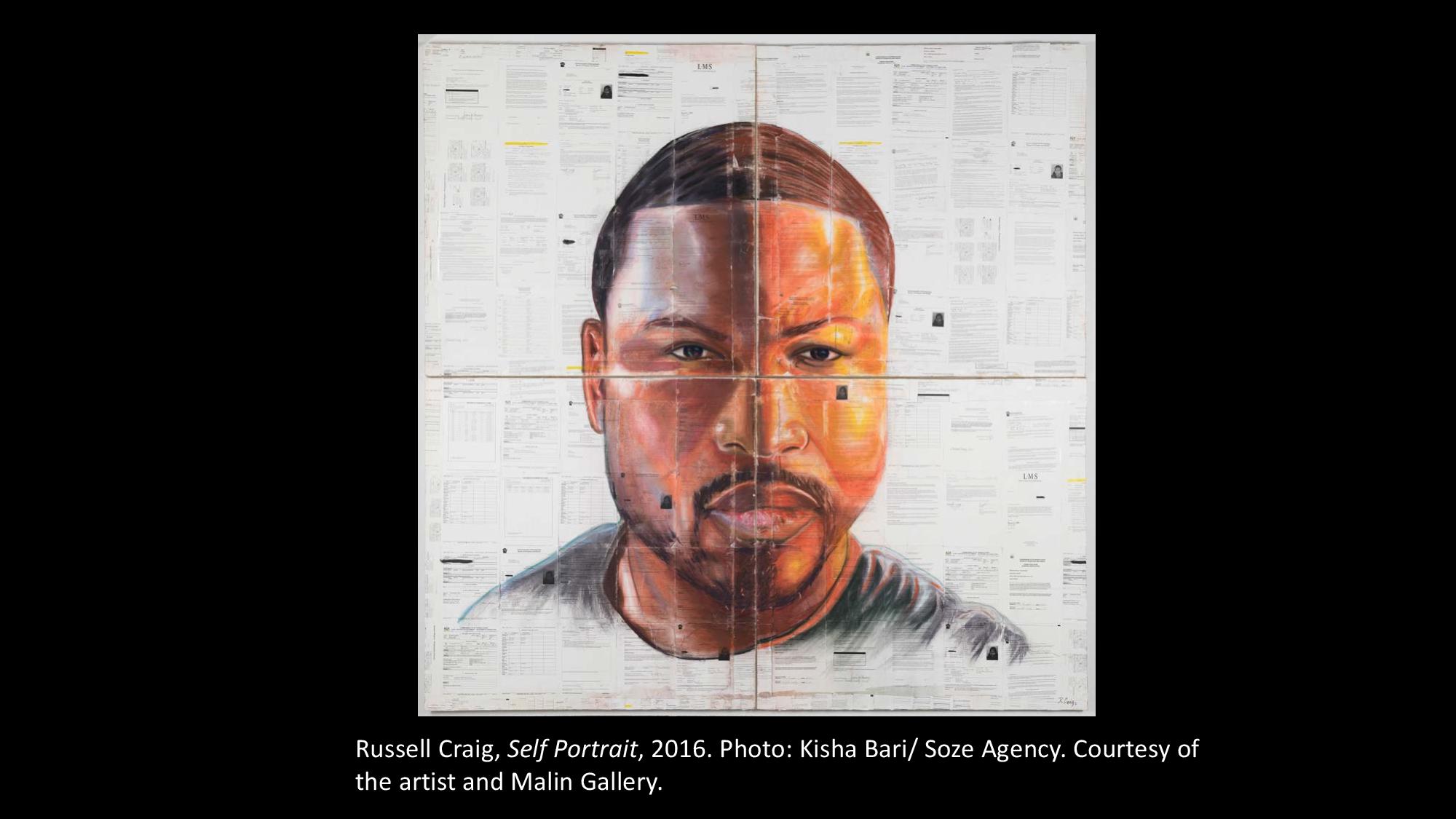

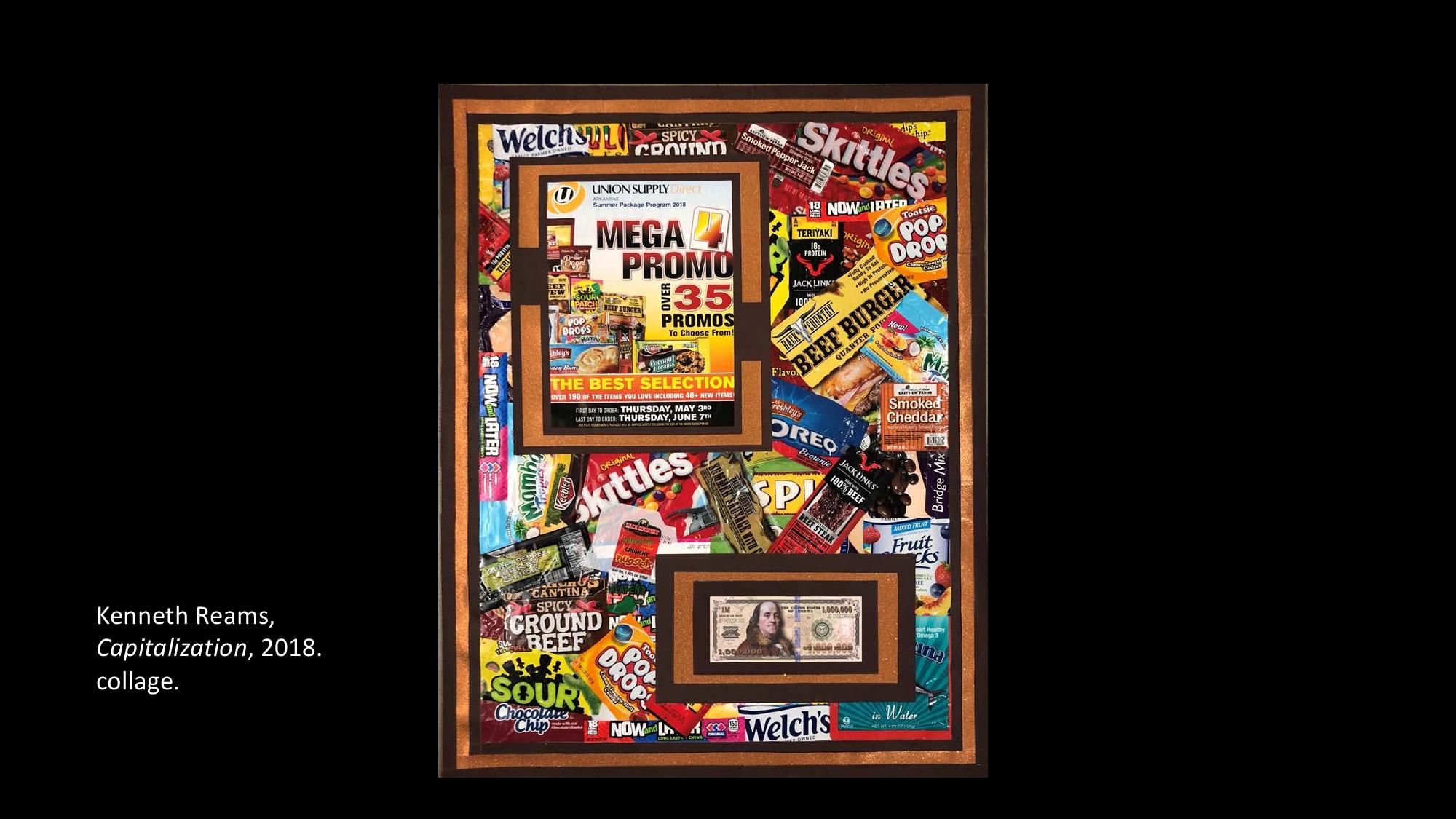

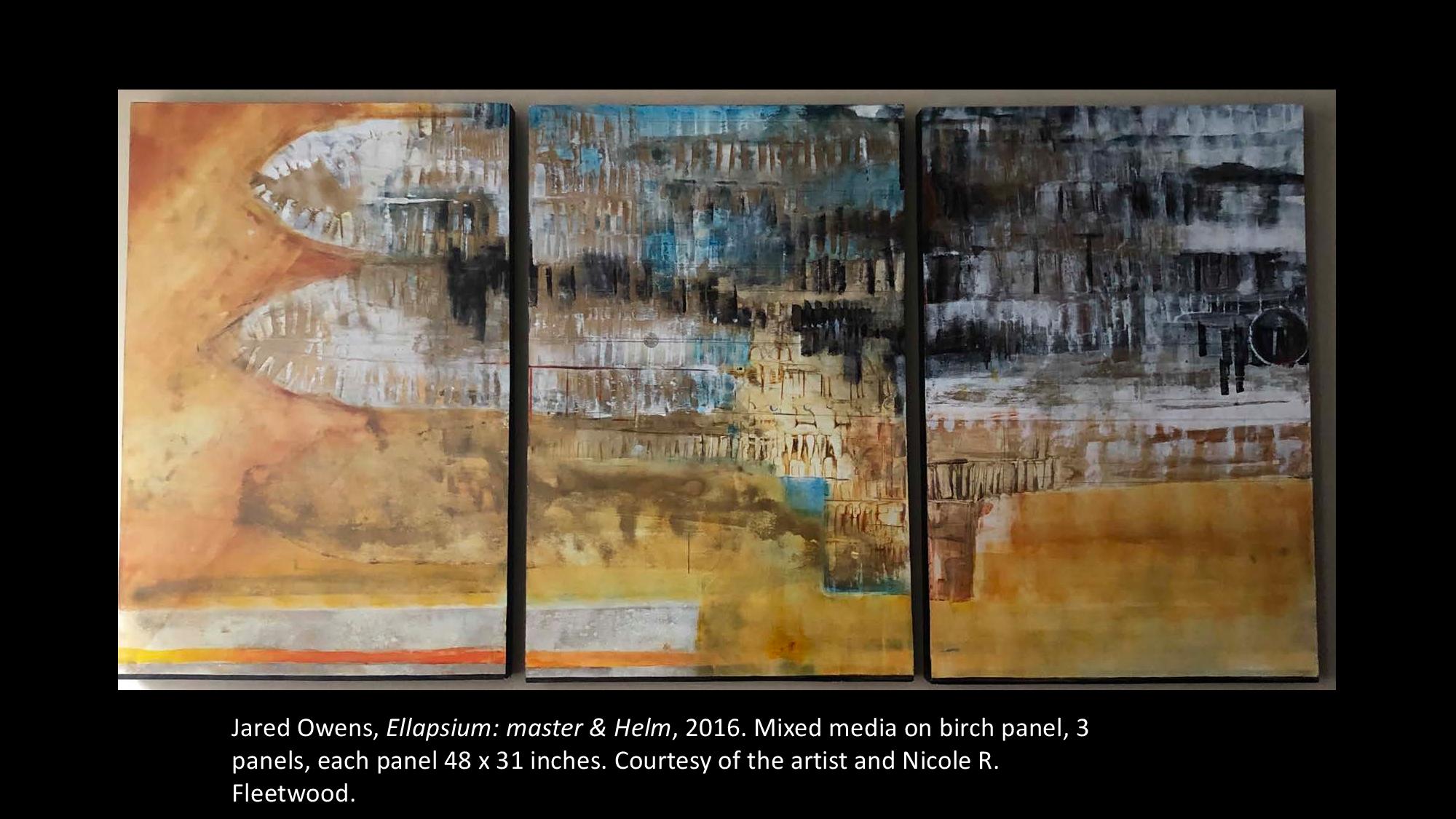

We spoke with Professor Nicole Fleetwood on the Black Lives Matter protests and her new book: Marking Time: Art in the Age of Mass Incarceration. In our interview we discuss her new book, the brilliant voices of dissent that cry out for freedom, abolition and the art of the U.S. Carceral system.

Dr. Fleetwood was also kind enough to provide us with artwork featured in her new book. *

Asia Art Tours For the power of protest art in social movements, Hong Kong’s Lennon Walls, graffiti art, and artistic tributes to the dead or wounded all come to mind. For the current uprising spurred by the Police murder of Breonna Taylor, George Floyd and so many others, what role have you seen art play?

Nicole Fleetwood: This is a very rich question. Visual art and advocacy have long been important to social justice movements, especially for black activists in the United States fighting against state-sanctioned violence, repression, and inequality. We can think of the power of “Black Lives Matter” painted in large block letters on streets across metropolitan areas in the United States. In my previous book, On Racial Icons, I wrote about the use of photographs of Trayvon Martin in protests after his murder and after the acquittal of his murderer, George Zimmerman. There’s a long history in black freedom struggles of incorporating images of people victimized and murdered by anti-black violence.

Nicole Fleetwood: This is a very rich question. Visual art and advocacy have long been important to social justice movements, especially for black activists in the United States fighting against state-sanctioned violence, repression, and inequality. We can think of the power of “Black Lives Matter” painted in large block letters on streets across metropolitan areas in the United States. In my previous book, On Racial Icons, I wrote about the use of photographs of Trayvon Martin in protests after his murder and after the acquittal of his murderer, George Zimmerman. There’s a long history in black freedom struggles of incorporating images of people victimized and murdered by anti-black violence.

AAT: And (if you’d had the chance to notice) what differences emerge between the art or images America’s mass media is focusing compared to what images those protesting have focused on?

AAT: And (if you’d had the chance to notice) what differences emerge between the art or images America’s mass media is focusing compared to what images those protesting have focused on?

NF: In our current moment, there are many ethical considerations about replaying videos of black people brutalized and murdered by police and white racists. Many activists and viewers have expressed concerns about how casually and frequently the news media replays clips of the murder of people like George Floyd and earlier Philando Castile. This horrific archive that has grown tremendously since the rise of smart cell phones have made the public more aware of the frequency of anti-black violence; it has led to a rising public consciousness but it has also led to a normalization, perhaps a desensitization to, of such images.

AAT: You have a powerful term for the art of prisons: Carceral Aesthetics. Could you describe this term in more detail and explain why you felt there was a need to invent this term in the first place?

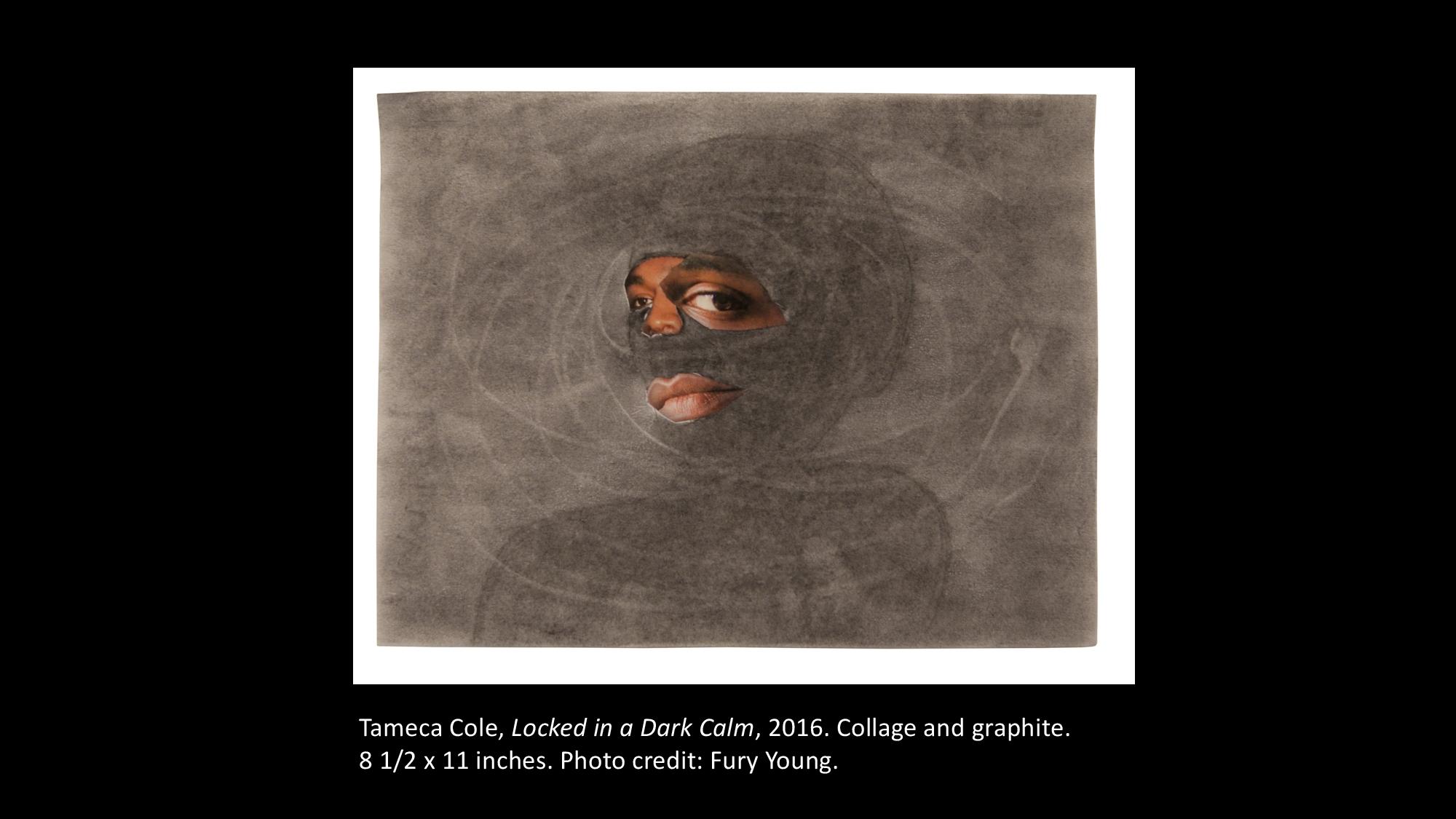

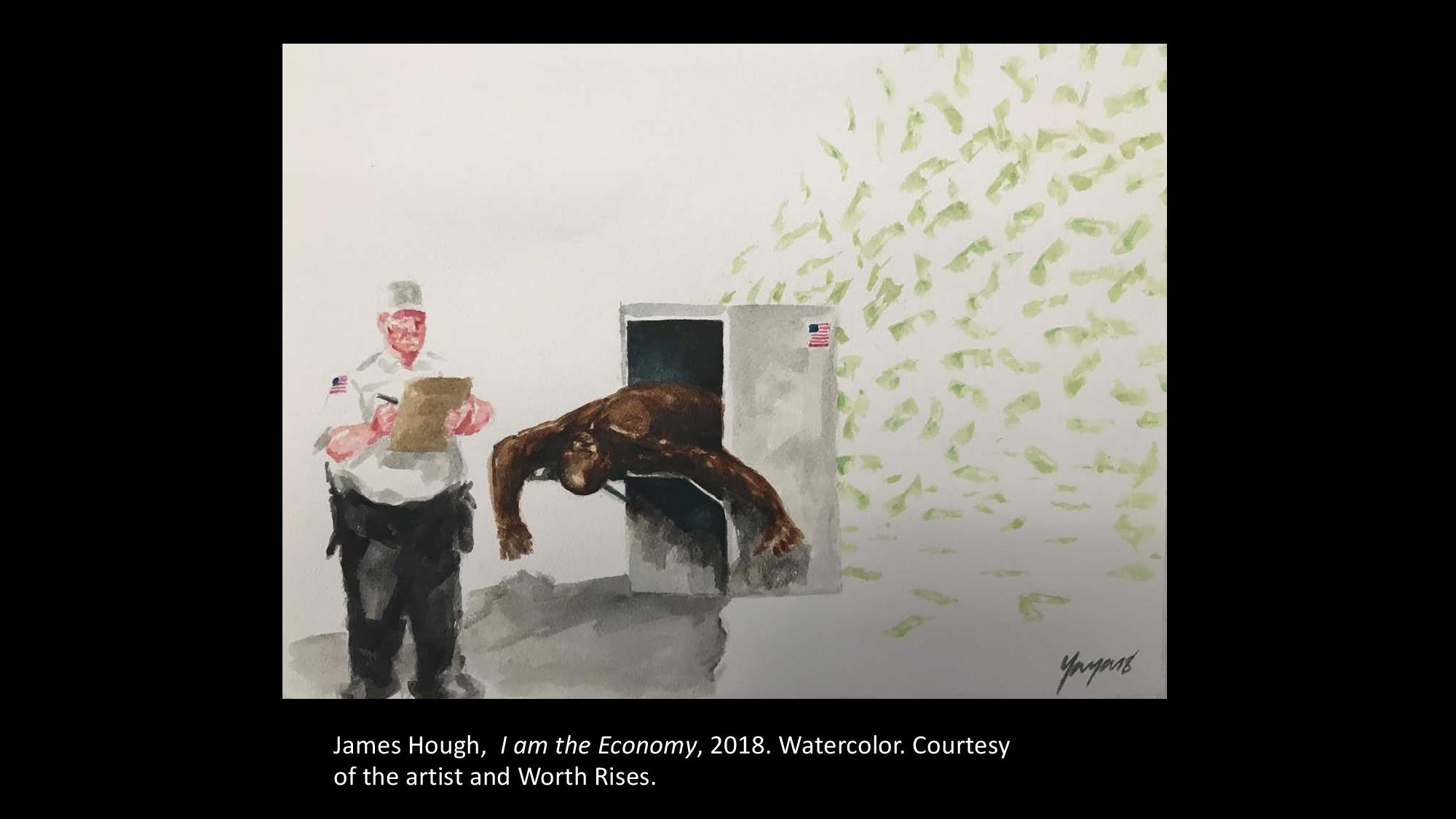

NF: I use carceral aesthetics in capacious way to refer to art made in prisons and also art made about the carceral state. I also refer to it as the production of art in the state of unfreedom. I also employ the term in a formal way to investigate how people held in punitive confinement use the very materials, space, and temporality of imprisonment for art making. It was important for me to develop the term to find fresh approaches to examine prison art; I wanted to move beyond conventional ways that people have engaged with these practices as outsider art, folk art, or untutored. I wanted to really engage the impact of prisons, policing, and surveillance on art and culture in the United States.

AAT: In explaining carceral aesthetics, you remark upon the cruel limits placed upon artists in prison. On cramped or absent studios, limited supplies some of which may need to be brought in as contraband, and simply being allowed free time to create. How does the carceral impose themselves on what the artist can create in prison, and how do artists rise above these limits?

AAT: In explaining carceral aesthetics, you remark upon the cruel limits placed upon artists in prison. On cramped or absent studios, limited supplies some of which may need to be brought in as contraband, and simply being allowed free time to create. How does the carceral impose themselves on what the artist can create in prison, and how do artists rise above these limits?

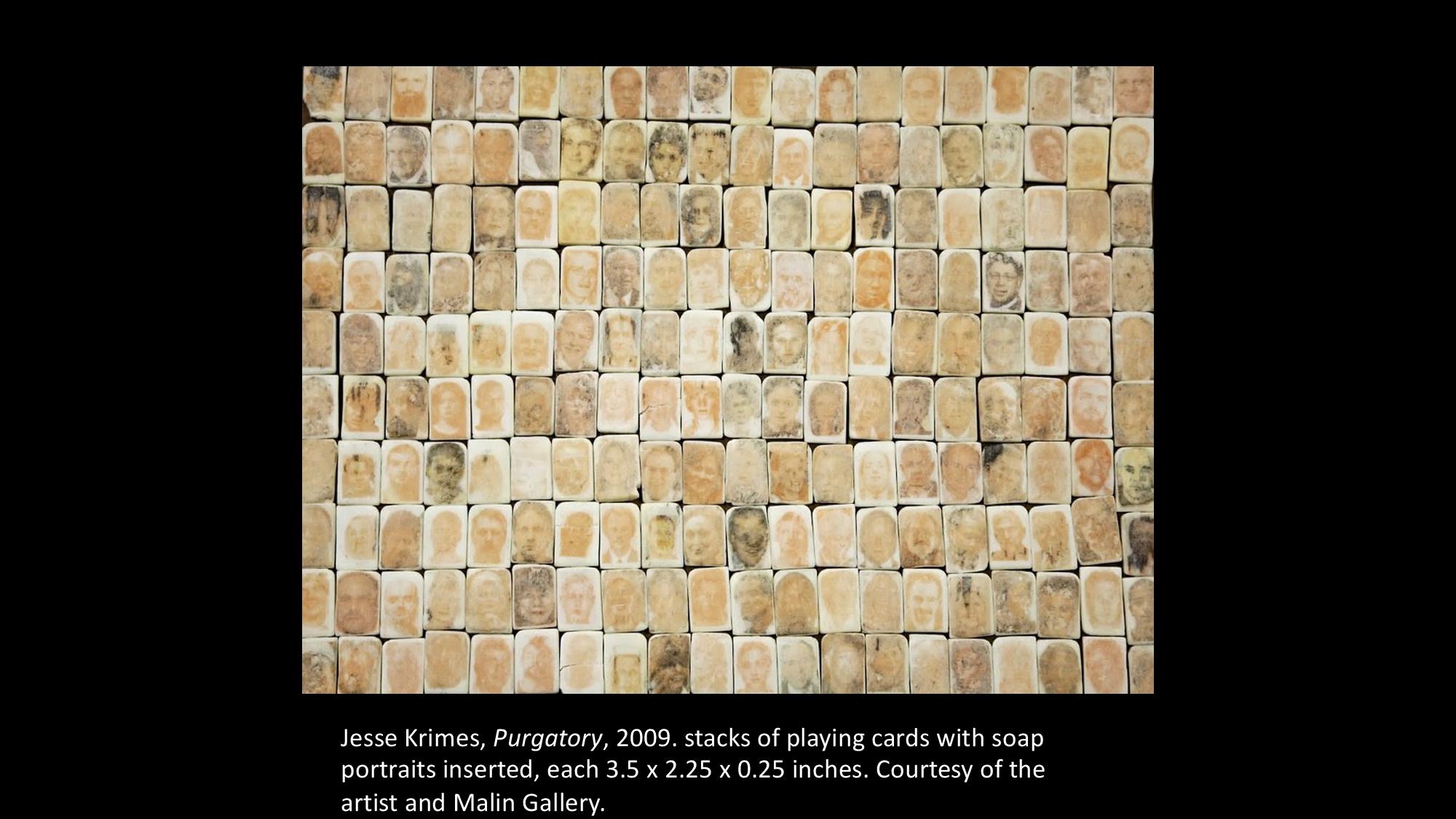

NF: Throughout the book, I delve into the conditions under which incarcerated artists make works. Some of these practices take place in state-sanctioned ways through formal art classes and organized collaborations between incarcerated and non-incarcerated artists. However the majority of art making takes place in prison cells and hobby rooms, in informal art collectives and in clandestine settings. I develop the concepts of penal space, penal time, and penal matter to understand the conditions of art making and how prisons shape the aesthetics and creative practices of imprisoned artists.

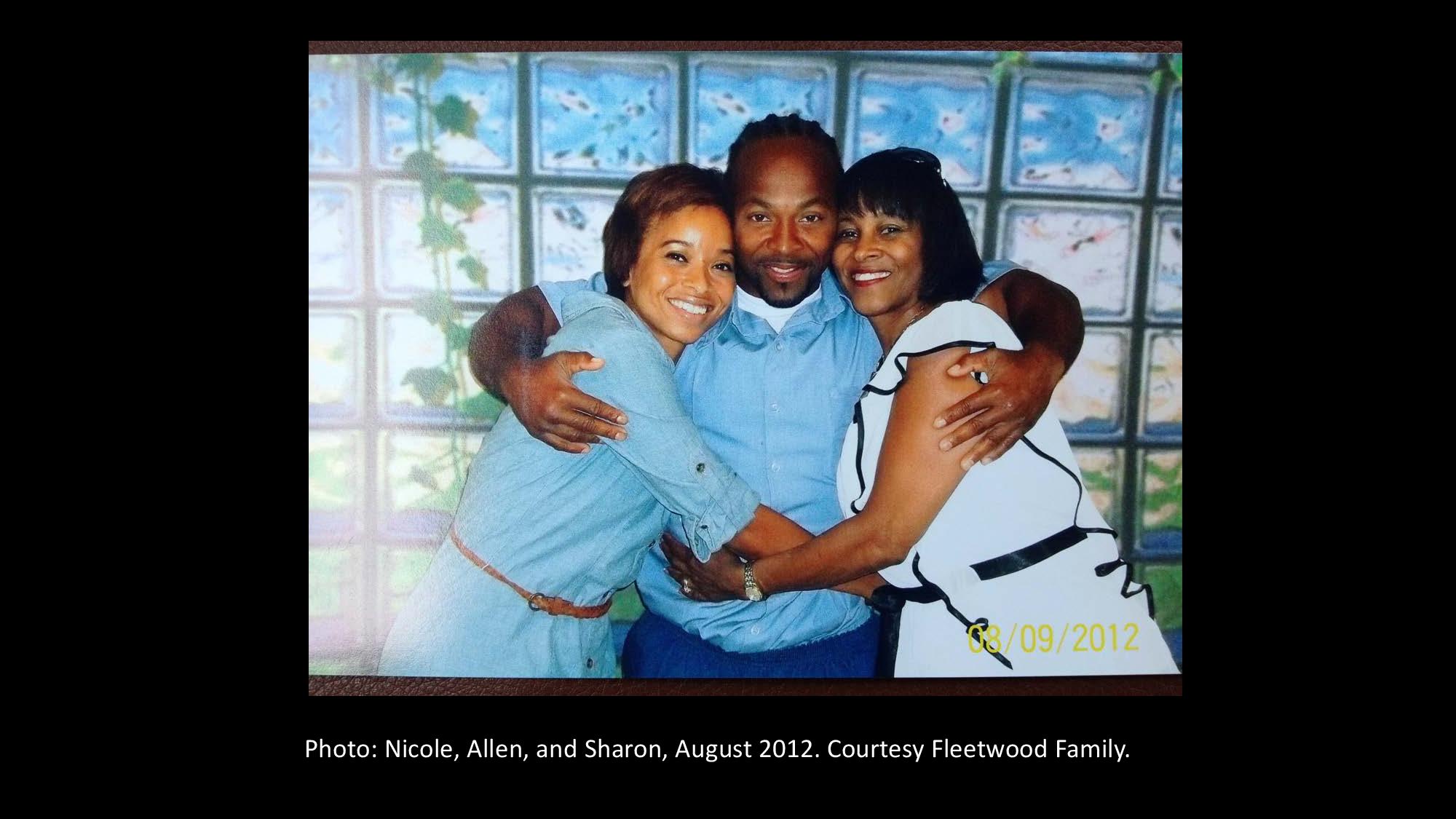

Penal space, I define, as both the built environment of prisons and jails and also the spatial relations structured through carceral state, especially how prisons reorganize the most intimate and loving relationships of those imprisoned, especially with family and community. Penal time is sentencing and how in our current legal system we measure punishment by the time people are held in captivity. Penal matter refers to the material constraints under which people make art and also the actual warehousing of bodies in carceral facilities.

Penal space, I define, as both the built environment of prisons and jails and also the spatial relations structured through carceral state, especially how prisons reorganize the most intimate and loving relationships of those imprisoned, especially with family and community. Penal time is sentencing and how in our current legal system we measure punishment by the time people are held in captivity. Penal matter refers to the material constraints under which people make art and also the actual warehousing of bodies in carceral facilities.

AAT: You also note that much of the artwork has a risk-filled life after its creation. Sometimes its traded for goods. Sometimes its confiscated. Sometimes its smuggled out. But very rarely (it seems) does it become part of the institutional memory of the prison. Broadly speaking, do prisons have adversarial relations with incarcerated artists? And when we think of the eternity that comes with an institution that can lock humans up for their entire lives, why don’t see more art within these institutions representing the experiences of those who spent their time inside?

AAT: You also note that much of the artwork has a risk-filled life after its creation. Sometimes its traded for goods. Sometimes its confiscated. Sometimes its smuggled out. But very rarely (it seems) does it become part of the institutional memory of the prison. Broadly speaking, do prisons have adversarial relations with incarcerated artists? And when we think of the eternity that comes with an institution that can lock humans up for their entire lives, why don’t see more art within these institutions representing the experiences of those who spent their time inside?

NF: This is a thoughtful and rich question, one that I can’t fully answer. What I will say is that the vast majority of art made by people in prison never leaves the prison walls. I wonder about the archives that the non-incarcerated will never have access to. I do think that prison art provides an extremely important counter-archive to state narratives of prisons and people in prison.

AAT: Finally, in our current era of museums and art auctions run as private hunting grounds for bored billionaires, I’m quite nervous about what will happen both to the art of this uprising and art from incarcerated people. For protest movements, how should we think through caring for this art even if the movement leaves the streets? And if not museums, galleries or the towering living room walls of billionaires, what institutions or spaces exist for this art to have a second life?

AAT: Finally, in our current era of museums and art auctions run as private hunting grounds for bored billionaires, I’m quite nervous about what will happen both to the art of this uprising and art from incarcerated people. For protest movements, how should we think through caring for this art even if the movement leaves the streets? And if not museums, galleries or the towering living room walls of billionaires, what institutions or spaces exist for this art to have a second life?

NF: Many share your concern; I certainly do. Both prisons and museums are extractive; they are organized around extractive capitalism. They acquire value by others labor—creative or otherwise. I think it is partly the work of those who want to reimagine what a museum can be and who also want to end prisons; it’s important for us to develop new approaches to curation—curation with its roots in care—and how artists and their labor are recognized, honored, and valued.

*Please do not share images without the Author’s consent. You can Purchase ‘Marking Time: Art in the Age of Mass Incarceration’ here – https://www.amazon.com/Marking-Time-Art-Mass-Incarceration/dp/067491922X