There are countless “Mutual Aid” projects that have appeared in the wake of Covid-19. In this interview we speak with an organizer of the Hong Kong to UK: Mask Circuit. They help deliver PPE to a United Kingdom that has badly mismanaged the response to Covid-19. Our conversation centers on their organization, solidarity as humans when government fails us as citizens, and building mutual aid.

Asia Art Tours: Could you give us a brief introduction (long or short as you’d like) to the HONG KONG to UK MASK CIRCUIT project?

Organizer (who wishes to remain anonymous) : The Hong Kong to UK Mask Circuit is a volunteer-led initiative to ship and deliver masks from Hong Kong to food banks, care homes, homeless and community outreach groups (including domestic violence shelters), and frontline workers in London. Our team comprises of people from different organizing groups,

AAT: How did this project come about? And what has been your success so far?

Organizer: I also owe a lot to my experiences of community care during the ongoing Hong Kong protests (as well their predecessor, the 2014 Umbrella Movement), whereby simple acts of practical solidarity––whether that is being one in a long supply chain of people passing water to one another, or shielding people from surveillance using umbrellas––were often some of the most impactful. Many of our members have also been part of groups in the UK that, being abolitionist in philosophy, focus on devising and imagining ways of existing, surviving, and thriving in the shadow of the state. All of these influences together is the origin story of this project––coupled, of course, with the abysmal incompetence of the British government to the coronavirus outbreak, that has already led to more than 33,000 deaths as of the time of writing (17 May).

(Hong Kong’s Protests were filled with useful tactics for global activists. Here is an example of the ‘human supply chains’ that would form, allowing protesters to pass supplies across great distances to provide reinforcement at the ‘front lines’ of the protest. Source: https://kpcnotebook.scholastic.com/post/protests-continue-hong-kong)

As of today, the Mask Circuit has donated a total of 12,400 masks: 5300 to 21 care homes, 2800 to 16 food banks, 950 masks 4 homeless, community, and domestic violence outreach organizations, 450 masks to 2 homeless shelters, and 3100 masks to two large trade unions as well as individual frontline workers. Apart from donations, we have been sharing links to our beneficiary organizations’ fundraisers and platforming their COVID-19 related work. At the same time as providing material support to people, we also hope to provide leverage for different unions, care homes, and organizations to demand better labour protections from the state and employers.

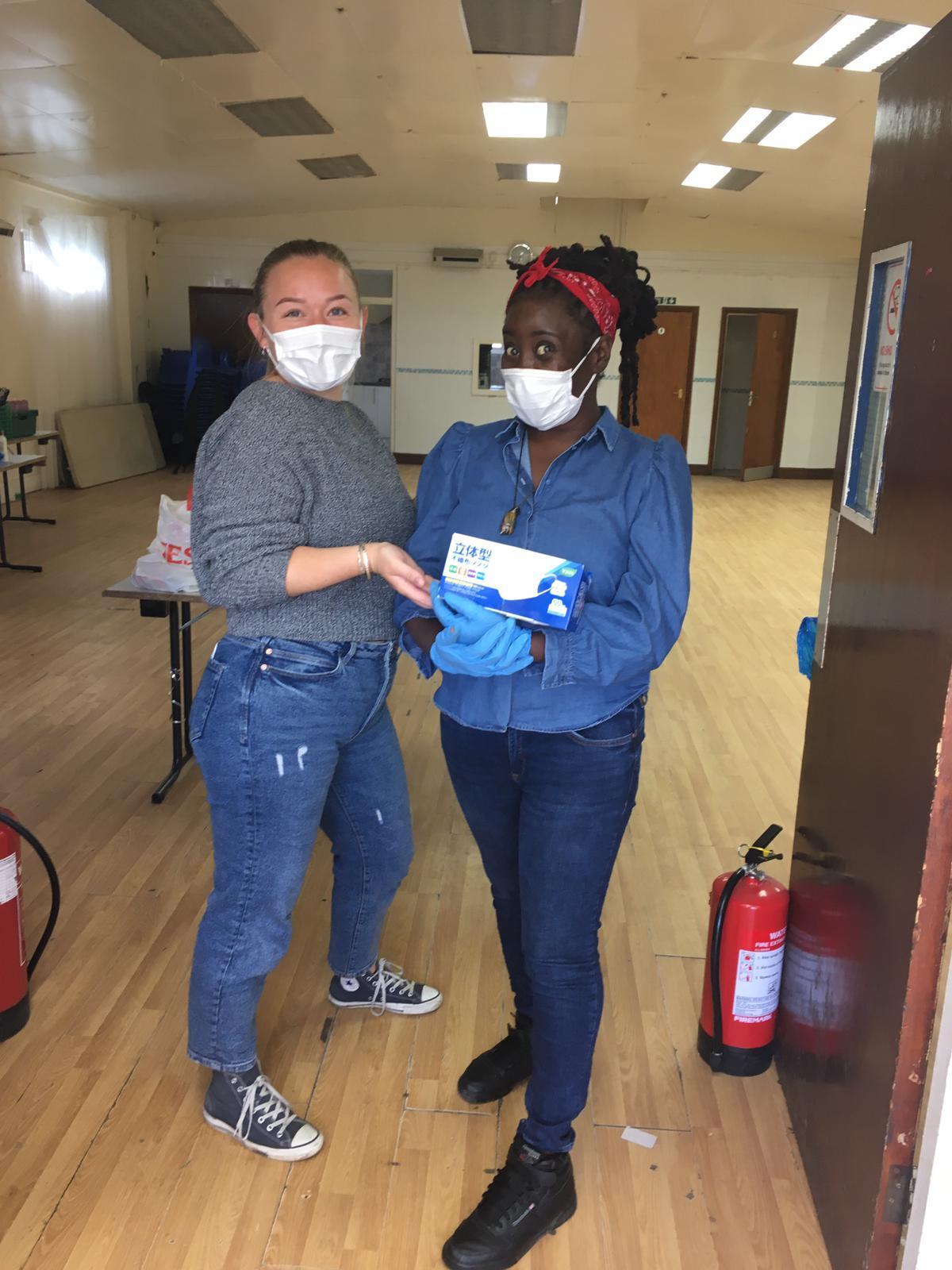

(Masks are delivered in bulk, then sorted by Mask Circuit volunteers, and then delivered to different organizations.)

For those who may want to try similar mutual aid circuits, what are some unanticipated obstacles or unexpected problems that your team had to solve?

One of the biggest obstacles for us has been making decisions about prioritization. Evidently, we can only supply as many masks as we have raised the money for (and even then, we are paying out of pocket for a significant portion of the costs): as a result, we have found ourselves having to choose which areas of London, which organizations, which care homes, and which unions and workers to target. And of course, these decisions are being made in a broader context of scarcity of PPE in the UK, including for medical staff. We have tried to navigate this quandary by targeting areas that have been most affected by COVID-19-related deaths, which are also the most impoverished parts of London; and by focusing our efforts on providing masks to frontline workers in care homes (deaths in which comprise ⅓ of all deaths in England and Wales) and to other precariously employed workers whose employers have demonstrated failures to provide PPE.

In addition to your project, are their other mutual aid projects that you would like to center or share as great examples of people helping people in this crisis? And do you think these projects will continue to exist or evolve post Covid-19?

In the UK, the government’s reaction to COVID-19 was extremely slow-paced. One of the organizations that pioneered the mutual aid movement that has flourished in response to COVID-19 was Queercare, a transfeminist autonomous care organization, providing training, support and advocacy for trans and queer people. It has produced extensive guidance on a variety of topics, such as safe receipt and delivery during COVID-19, how to wear a mask, what types of masks to buy etc––some of which we have adopted in our own procedures.

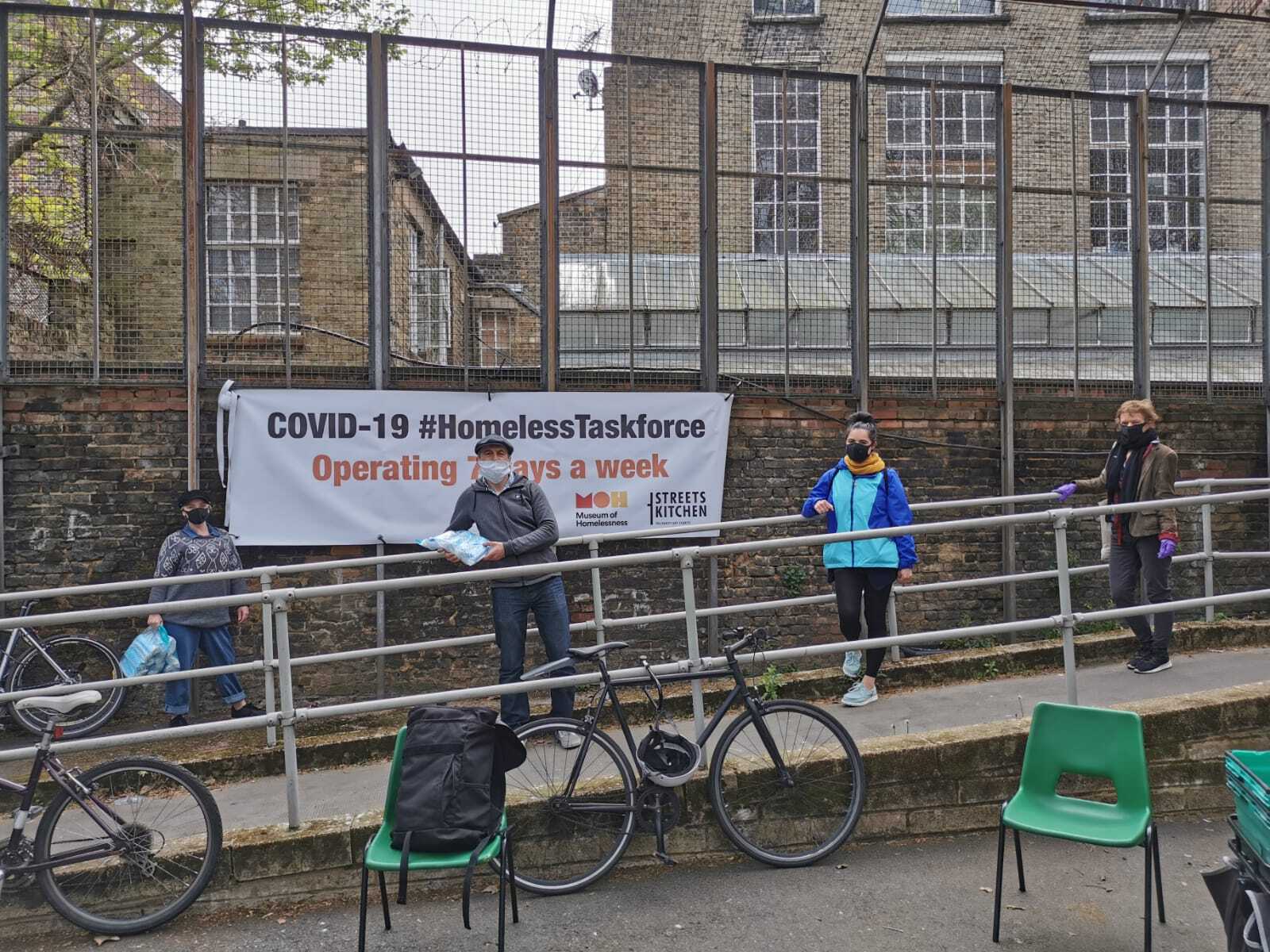

Since the start of the outbreak, there have been many mutual aid groups established across the UK, with people in local communities coming together and helping their vulnerable and shielding neighbours with anything from groceries to walking their dogs. Existing migrant support groups, homeless shelters, and food banks have seen their rates of service provision multiply, with volunteers stepping up from all corners to extend support: Streets Kitchen, Hackney Migrant Centre, Haringey Migrant Support Centre, Praxis Community Projects, North Paddington Food Bank, just to name a few. Many abolitionist and detention support groups, such as Prisoner Solidarity Network and Bail for Immigration Detainees, have been fighting for people to be released from prison and immigration detention centres into safe accommodation. Sex workers have come together to support one another with a hardship fund.

(These masks were delivered to Akwaaba, a non-hierarchical social centre for migrants in Hackney, where members share food, access resources, socialize, and take part in classes and activities. Between 250-300 people regularly come to Akwaaba.)

It would be remiss not to talk about the role of unions and tenants’ groups organizing in support of people suffering the effects of COVID-19. United Voices of the World are currently running a campaign to demand justice for Emanuel Gomez, an outsourced cleaning worker at the Ministry of Justice who died of suspected COVID-19. He was forced to work because of his employer’s failure to guarantee occupational sick pay. UVW says that Emanuel “hadn’t eaten at all, or had barely eaten, during the 5 days before his death and was so weak in the hours before his death that he barely knew where he was or how to get home”. Apart from UVW, Independent Workers of Great Britain (IWGB) have recently filed a legal challenge against the UK government with the High Court over its failure to provide satisfactory income and sickness protection to millions of low-paid and self-employed workers. After a company tried to make 10 medical couriers redundant, including leaders within the IWGB, the union also began to mobilize around the rights of couriers and other ‘gig’ economy workers. London Renters’ Union are also currently organizing a rent strike campaign, and have been providing essential support to tenants who are being forcibly evicted out of the homes.

As to whether these groups will continue to exist post-COVID19, I think it’s important to remember that many of these groups and networks have always existed––for marginalized people who have never been able to rely on the state, community has always been a lifeline. So my answer is that those groups that have always existed, will continue to exist, and provide the resources for survival that they have always done, for the communities they have always served.

As for those mutual aid networks that have formed with no clear political orientation or vision, for them to transform and be sustained beyond this current moment, their members will need to articulate what a future that is centered on community care will look like––while also acknowledging which communities are the most in need of care due to race, class, gender, and ability, in an ethic of solidarity rather than charity. We have seen challenges to this already, through the involvement of councils and local government in mutual aid groups, that may lead undocumented, homeless, and other marginalized people, especially people of colour, to avoid them for fear of arrest, detention, or deportation.

(Mask Circuit Volunteers, Kay & Hanna delivering 1450 masks to food banks, mutual aid projects & care homes in Camden, Hackney, Bethnal Green, & Homerton).

While praising your project, I do want to highlight that in a better and more just world, your project should not need to exist. What has forming these mutual aid networks taught you about the neoliberal governance in the UK/US and globally that seems designed to deliberately fail for the most vulnerable (and to increase the pool of risk for the many at the behest of the few)?

We agree that in an ideal world, our project should not have to exist. In a world where political communities continue to be organized in units of nation-states, and where the state is seen as the holder of the monopoly of coercive power as well as the provider of security and fulfiller of basic needs, it should be the state that is creating the conditions for safe and health living for its citizens. Even practically, it would be a lot cheaper for governments to go direct to suppliers to purchase bulk quantities of masks, or to mobilize resources to produce masks in the country itself.

However, as we know from the work of anti-racist activists and thinkers, especially Black Feminist and anti-colonial writers, the Western model of the nation-state has always been premised on a particular mode of exclusion that was created in order to colonize, subjugate, exploit, expropriate, and control Black and indigenous people and other people of colour. If these very people and communities were already excluded in the founding logic of states, it is a fanciful illusion to think that the state would ever be able to provide safety to them.

Indeed, what we see from the UK’s response to the coronavirus outbreak is that the government has never strayed from its original, much-criticized ‘herd immunity’ policy: it is simply that the people who are dying for the good of the wider public are those who are already at closer proximity to death by virtue of their racialized and class position, and thus there is no need to give that phenomenon a pseudo-scientific name. Black men and women are nearly twice as likely to die with coronavirus as white people in England and Wales. Compared with the rate among people of the same sex and age in England and Wales, men working in ‘low-skilled’ occupations, such as security guards, had the highest rate of death involving COVID-19, followed by people working in social care––occupations which are disproportionately taken up by BME people, especially Black people. The business of death is going on as usual in Britain. All the more so now, when the government is prematurely easing lockdown measures, essentially forcing people to go back to work “if they cannot work from home”, without any safety equipment, evincing its fundamental prioritization of profit over human life.

(These masks were delivered to Revivify CIC, an organization delivering meals and food parcels to local vulnerable and isolated residents in Croydon. Please support this vital work here: revivifycommunity.co.uk/donate-money)

In the UK, anti-racist activists have been organizing in mutual aid networks for decades, as a response to the rollout of austerity policies under Margaret Thatcher that saw a significant depletion of community resources, especially those servicing the most marginalized and precarious people in society.

In this tradition, at the start of the pandemic, some daikon* members, who are also volunteers in the Mask Circuit, collaborated with a group of abolitionist organizations such as Community Action Against Prison Expansion (CAPE), Haringey Anti-Raids, Lesbians & Gays Support the Migrants (LGSM), Sisters Uncut, SOAS Detainee Support, Unis Resist Border Controls (URBC), and Wet’suwet’en Solidarity UK to write a collective statement entitled “The state will not save us, only we can save us’: a collective response to Covid-19”. In it, we grappled with the need to interact with, while also resist, the incursions of the state––words which remain true to what we think today:

In light of government inaction, many are calling for exceptional measures, framing this moment as one of “crisis” requiring urgent action and attention. It is true that we need urgent action, but we also must recognise that the very idea of ‘exception’ obscures the reality that the people that our government is effectively willing to let die have always lived in precarious conditions, subject to the vicissitudes of an economic system designed to place profit and power above people’s lives. Not only does the logic of “crisis” exceptionalise, it creates an opportunity for the state to consolidate power – increase surveillance, restrict freedom of movement – in the name of addressing the “crisis”. Indeed, it was recently announced that police and immigration officials will be granted emergency powers to detain people suspected of having Covid-19. If we have learnt anything from the ongoing racist surveillance and criminalisation of Muslims and other racialised communities under the “War on Terror”, we know that we must be vigilant against the intensification of police and border violence in the name of a racialised “War on Disease”.

When we call for the state to act to prevent death as a matter of urgency, then, we do so with the knowledge that the underlying crisis is ongoing, and with the hope that any actions taken now will reverberate beyond this seemingly “exceptional” moment. And when we emphasise the urgency of “quarantines” and physical distancing, we do so as a method of collective care that reduces the very real risk to the most vulnerable, whilst resisting a parallel expansion of state coercion and surveillance.

One of the best articles I read this year, discussed the transnational supply chains of Hong Kong Protesters. How ordinary people in other countries moved by the protests, formed networks and chains of mutual aid to help support the movement within Hong Kong. How can we build other circuits of mutual aid to bypass the global supply chains of Capitalism? And how should we be building more transnational links for the protests that will likely reemerge post Covid-19?

I think the key is to start with identifying a practical aim––whether that is transporting masks, or trying to build a common thread of understanding between different groups––and to start building from there. Too often organizing starts off with ideology, and attempts to find its practical foundations from there; I would say that more important is the doing and the thinking together.

(These masks were delivered to Street Kitchens and the Museum of Homelessness. These groups work in solidarity with the homeless community, providing daily outreaches with food, clothing and info in the UK)

Lastly, Does Diaspora and the politics of Diaspora offer another strand of activism and framework for organizing entirely? Another way to build connections and mutual aid with one another that defies borders and boundaries?

I think the key to organizing is not to fixate on the identity aspect of ‘displacement’, but to look for similarities in histories and struggles, on which to focus our organizing.

For more, check out the Hong Kong to UK: Mask Circuit