At Asia Art Tours, one of our main priorities is complicating or interrogating the dominant stereotypes we see used by the travel industry to sell their destinations. For Japan this is the image of the Geisha or the ‘obedient’ and ‘polite’ Japanese woman. When those who live in Japan know that Japan historically has one of the most complex, loud and dynamic feminist movements in the world.

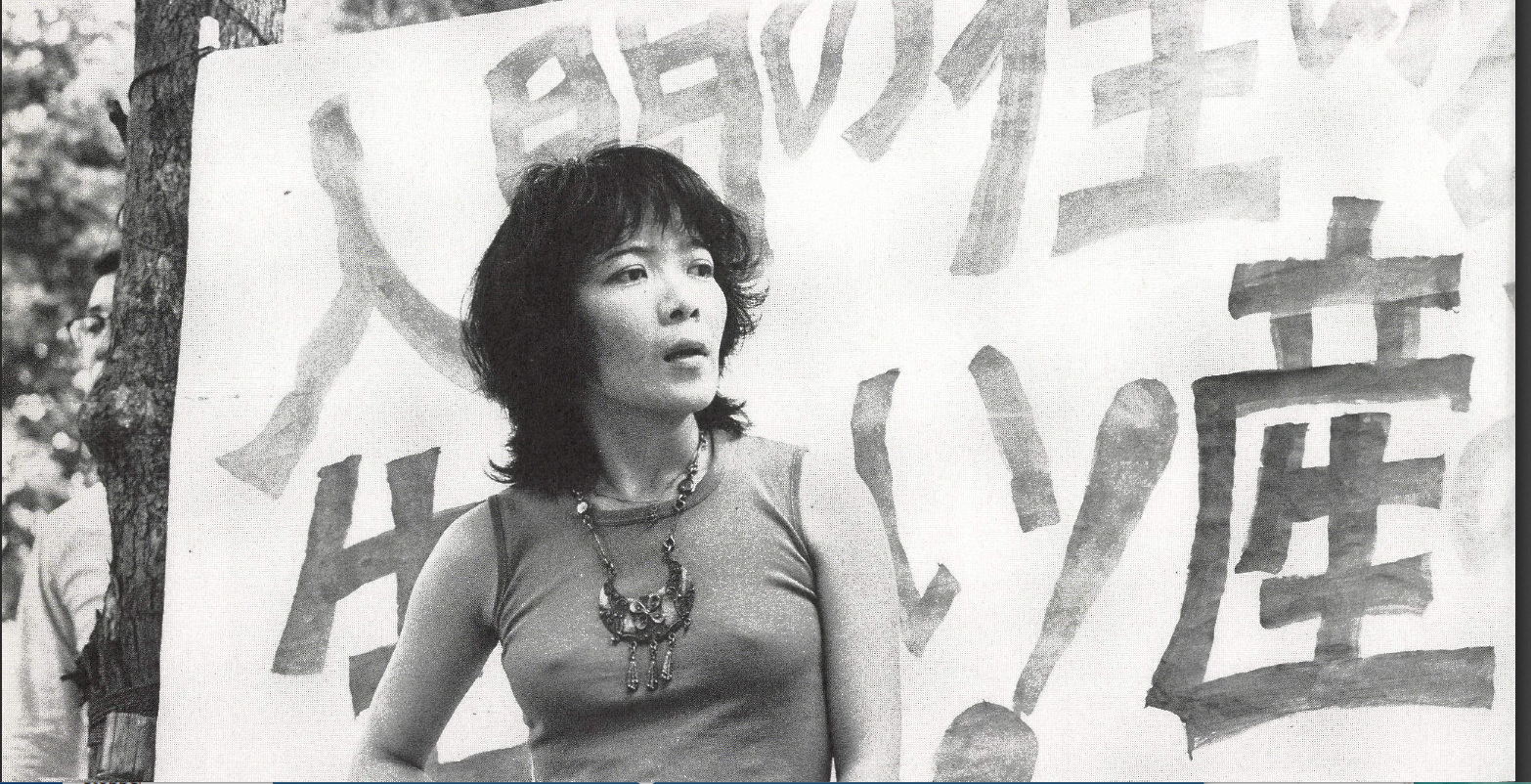

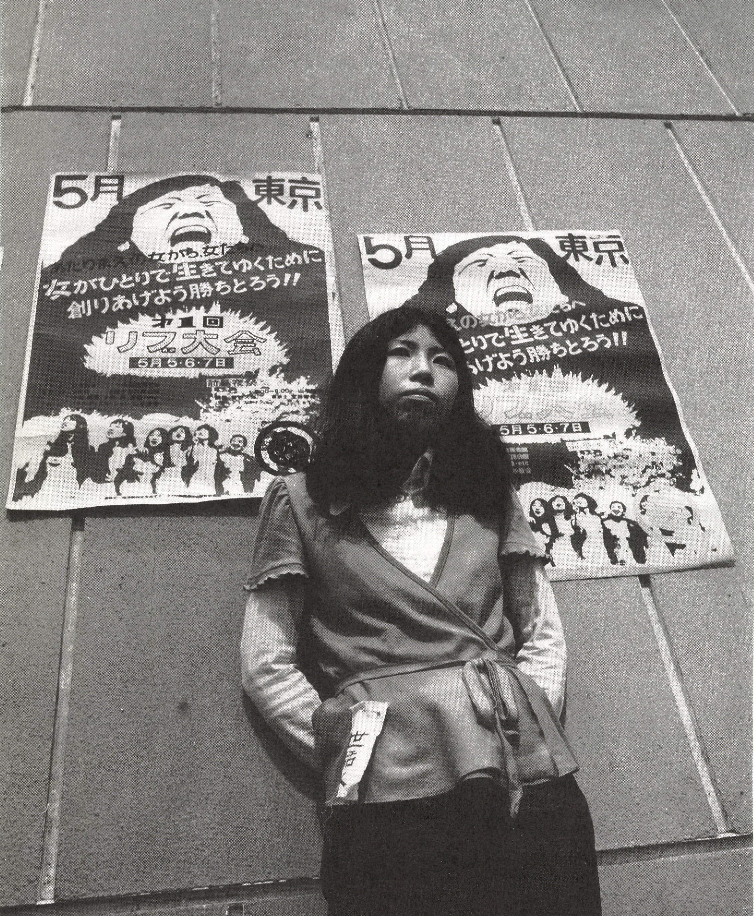

To dismiss and interrogate these stereotypes of Japan, Asia Art Tours was extremely fortunate to speak w. Dr. Setsu Shigematsu of UC-Riverside. Her book SCREAM FROM THE SHADOWS : THE WOMEN’S LIBERATION MOVEMENT IN JAPAN, is one of the finest texts on Japan’s long history of feminism and activism.

We spoke with Dr. Shigematsu at length about the history of feminism, how Japan and Western feminists diverged, and where the feminists of Japan stand today. For a travel company that highlights the strength and diversity of Japan’s women, please check out Asia Art Tours: Feminists of Japan Tour!

ASIA ART TOURS: To first center on yourself, could you tell us a bit about your background? Were there any personal experiences that led to your interests in Feminism?

SETSU SHIGEMATSU: I was born in Tokyo, but grew up in London, England and the x-burbs of Vancouver, British Columbia. My Japanese parents were progressive for their generation and although my mother didn’t call herself a feminist, the ways she described the gender inequality in Japanese society made me very conscious of it as a child growing up. I remember her describing old Japanese sayings like a woman should walk three steps behind her husband and her telling me about the story of Madame Butterfly that she watched many times performed by Takarazuka. As a young teen, I thought Cio-cio’s suicide was completely absurd and the romanticized sexism of this story stuck with me. This consciousness grew, and after I learned about rebel Japanese women as an undergraduate in books like Reflections on the Way to the Gallows, which tells the stories of anarchist anti-imperialist Japanese women who were put to death by the state, this further piqued my curiosity. For my dissertation project, I wanted to research Japanese women revolutionaries and radical feminists of the era of the 1960s-1970s.

2. What specifically inspired your work “Scream from the Shadows?” Did you have any goals in mind when composing the text? And did you have a reader in mind for whom you were creating the book for?

I believe that it was necessary to counter Orientalism and its prevailing image of Japanese and “oriental” women and general ignorance about Japanese feminism. I wanted to make radical Japanese feminism not only legible to a wider audience, but also analyze and argue its relevance for 21 century politics. I was writing an academic book, but I wanted to do justice to the women of the movement, whom I came to know and befriend through my years of research.

3. For Scream from the Shadows… why did you choose to focus specifically on the feminism of the 1960s and 70s… and what historical or cultural context is important in understanding the thinking of the feminists that you studied (if it’s possible to answer such a broad question!)?

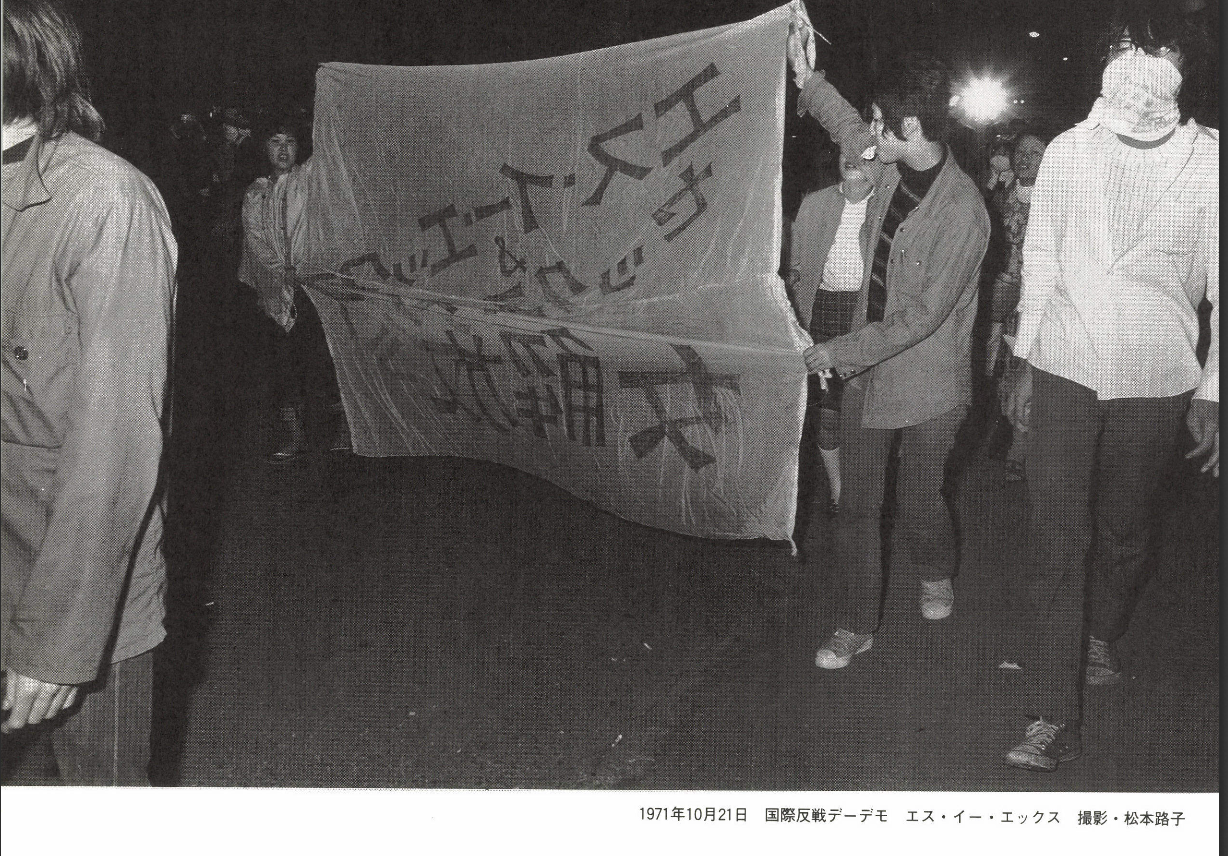

This period is important within the larger internationalist context of the global 1968. The movement arose as part of a worldwide uprising and movements from other countries and continents were cross-fertilizing each other. I write about how both domestic anti-Vietnam War movement and leftist student movements were the immediate context and how news about the U.S feminist movement, discourses of black power and the Black Panthers were also catalysts.

– In this vein… should we think of Uman Ribu as one branch of feminism of this time-period. Or AS the Japan Feminist movement, in its totality, of this time period?

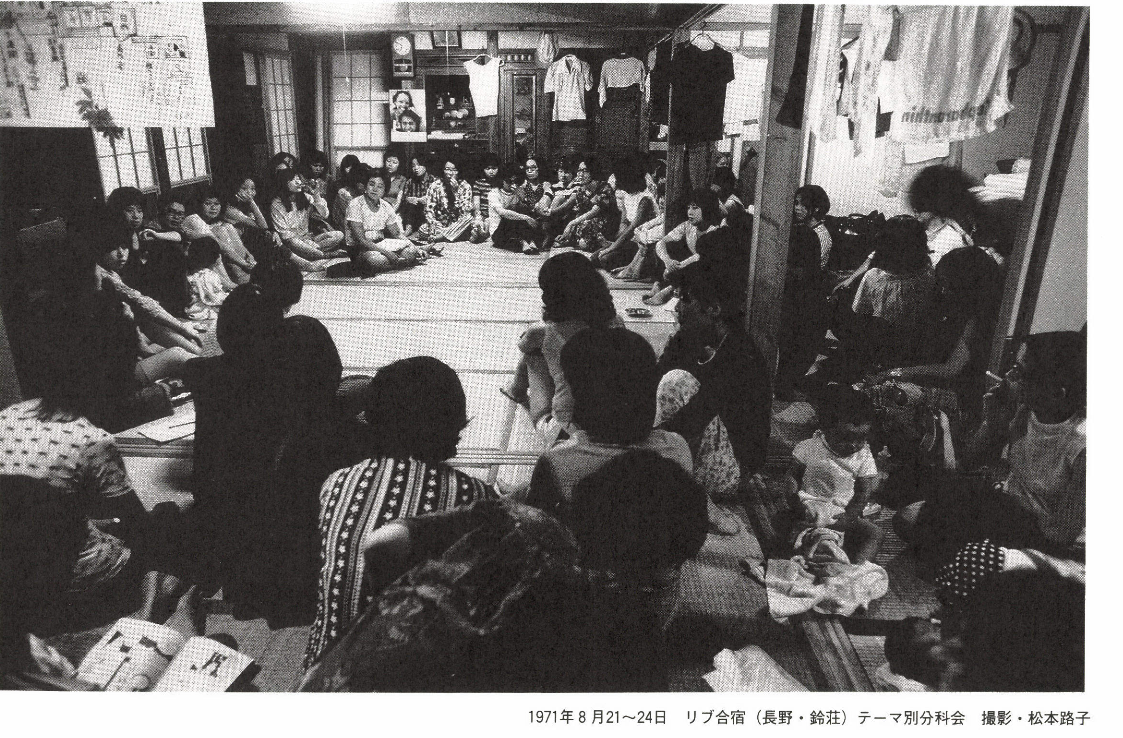

Uman ribu was specific to this time period and one very new branch of women’s liberation or Japanese feminism. Its activists were critically responding to the sexism in the male dominated student movement and New Left, and reacting critically to cultural shifts of the era such as “free sex.” But its activists also learned from the existing Japanese leftist women’s movement and understood that there needed to be a paradigm shift.

4. Again, broadly speaking, what are some of the stark differences between the Japanese feminists you studied, and their western counterparts? What would most stand out to a Western Feminist to their counterparts in Japan? (This can be in terms of their ideology, their demographics (MIDDLE CLASS) or their goals)

The demographics were similar–educated middle class women primarily in their 20s and young mothers. I think that one of the most significant differences between this movement called uman ribu was that in contrast to white liberal U.S. feminism, these activists didn’t center of the concept of “women’s rights” (kenri) or equality with men as its goal. In other words, it didn’t adhere to liberalism or liberal feminism which emphasizes individual rights.

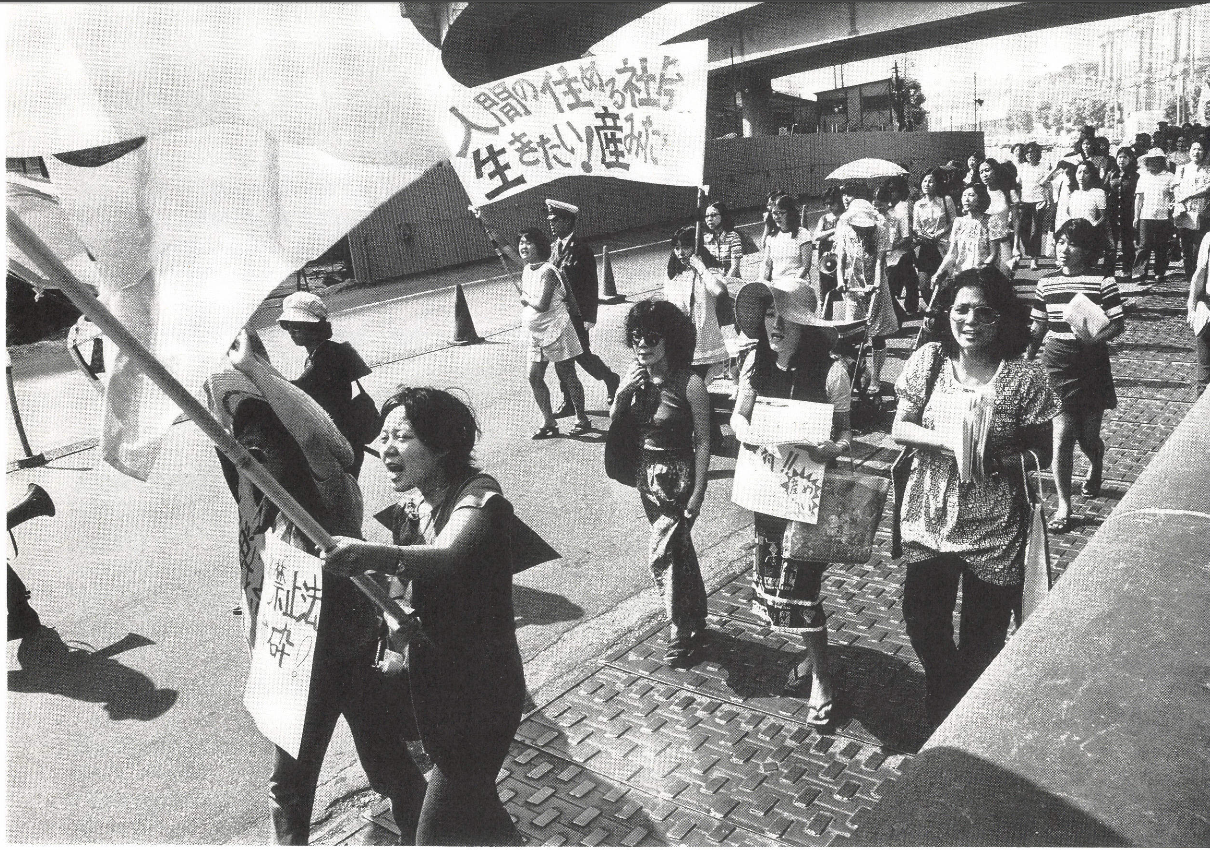

I describe the movement as radical feminist movement, not just because of the militant rhetoric of some of its activists – but because they were calling for a complete transformation of the socio-economic-cultural foundations of modern Japanese society: they were calling out capitalism and patriarchy and the family (ie) system and Japanese imperialism and all the ways in which these systems intersected to discriminate. Sex discrimination was one of their key concepts.

4b. You have this wonderful passage in chapter 1 where you state-

The close ties to the government and investment in women’s roles as good housewives and wise mothers formed the basis of the interlocking relationship between the Japanese family and state capitalism that ūman ribu criticized as the reproductive unit of a discriminatory social system

Could you touch briefly upon this. What criticisms or insights did the Uman Ribu have as to Women’s Roles in the social reproduction of State Capitalism in Japan… And what aspects of this reproduction were they trying to change through their activism?

This question helps flesh out my previous comments, because, for example, rather than Japanese women seeking to be equal with their Japanese middle-class counterparts, they called Japanese salary men “slaves of the corporation.” This kind of militant discourse forwarded a powerful, fierce critique of patriarchal state capitalism, if not at times aiming for exaggerated rhetorical effect since Japanese men were not slaves in the sense of of chattel slavery, but they used such language to highlight their relative state of oppression and unfreedom. In other words, uman ribu activists called out this sex-based discrimination whereby men, not because they wanted to subordinate their lives to a corporation, but men were the paid labor force for Japanese capitalism and women were the key collaborators by being the unpaid domestic laborers who reproduced this system.

5. Is it important to understand the leaders of Uman Ribu? (figures such as Iijima Aiko and Tanaka Mitsu ) ? If so what were some of the central ideas of the leaders… and how were these followed (or at times opposed) by the followers of the Uman Ribu movement?

I understood Iijima Aiko as a forerunner to the uman ribu. She was a life-long socialist activist who eventually broke away from the socialist party. She was married to the man known as the father of Japanese Trotskyism, Ota Ryu, but left him stating she experienced “ the oppression of her sex” in her marriage. Iijima didn’t identify as uman ribu. The biggest distinction between Tanaka Mitsu, who has become the iconic figure of the uman ribu movement and Iijima had to do with their difference around sexual politics. Tanaka politicized sexuality like no other publically known Japanese feminist before her. Her discourse was unprecedented from the way she spoke about her own sexual abuse as a child to the ways she called out the chastity of Japanese housewives as being complicit with the rape and violation of comfort women. Tanaka was a charismatic woman and often times leaders of such paradigm shifting movements are formidable individuals whose discourse was striking and even shocking because they were willing to decry publically what most others wouldn’t dare to say.

Iijima didn’t center or emphasize sexuality in the way Tanaka did. Iijima was more concerned with critiquing Japanese society’s postwar prosperity as being complicit with the war efforts in Vietnam, whereas Tanaka was more concerned with liberating onna (woman) and the specificity of onna’s (woman’s) oppression as a sexualized subject. Tanaka and some of her activist friends went so far to work as hostesses and they did it with a kind of political consciousness to defy the good chaste woman/bad loose woman dichotomy that Japanese patriarchy imposes to divide and hierarchize women.

– And to center the Uman Ribu in the present, why do you think that their calls for anti-imperialist feminism, the notion of Japanese women as the victim-accomplice and recognizing Women’s role in the production of war… does not seem to be as prominent in modern feminist movements (in Japan, or elsewhere)? Especially as multiple wars are waging currently and Japan (via Article 9 and renewed Neo-nationalism) is aiming to once again have the ability to wage offensive or imperialist-motivated war.

This is a great question. But I think that it stems from the overemphasis on “women’s empowerment” versus understanding women’s complicity in state violence. Japanese feminists have a lot to offer in this regard because most have resisted representing women as innocent victims and been critical of the national-imperial power and class privilege in larger world systems.

Again, when we talk about feminisms, I think that its important to understand the contributions of feminisms of color and third world feminism and how their critiques have been much more intersectional with their critiques of the simultaneity of various axes of power. Increasing women police officers or women soldiers for imperialist war efforts was not the form of empowerment most feminists in Japan would advocate. These would be examples of greater complicity with state violence and demonstrate how equality with men should not be the main goal of feminism.

6. What was the Ribu’s critique of the housewife and what alternative models did they offer (I’m thinking of their construction of female-only communes)

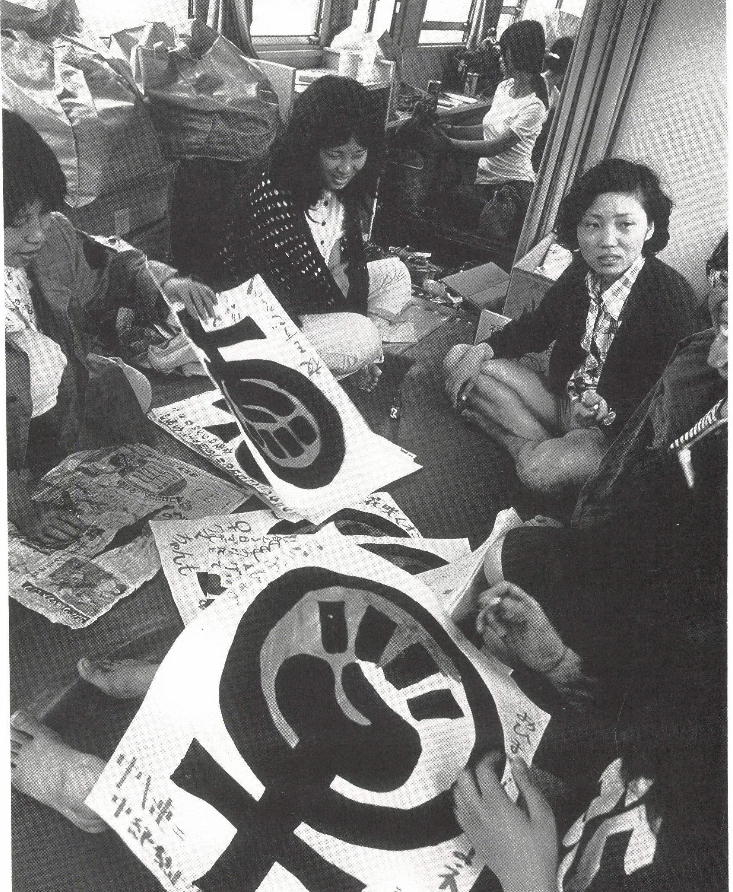

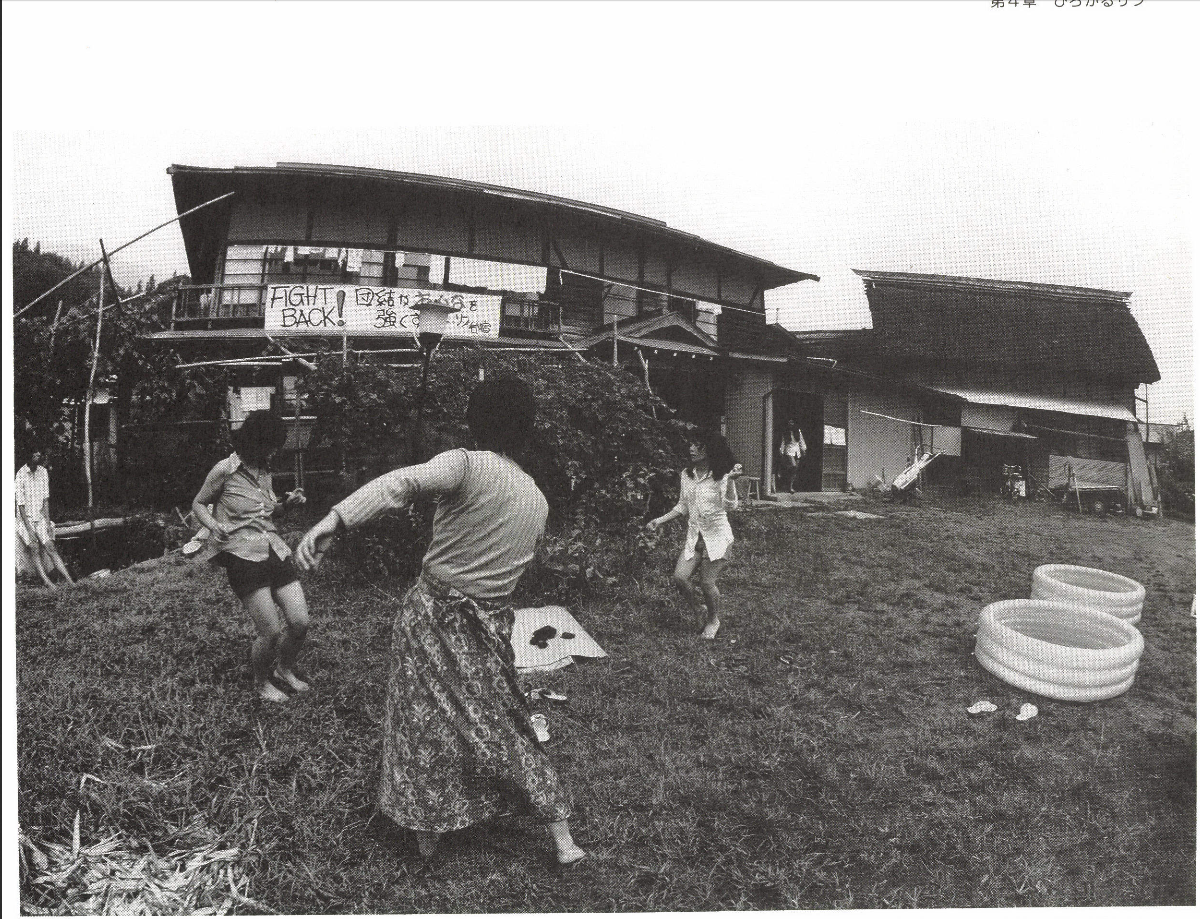

Ribu criticized the patriarchal ie (family) structure, which historically privileged the eldest son and centered on a male-head of household. Instead, some ribu women refused to marry, and had children, deliberately out of so-called wedlock and lived with other women in communes to raise them. Many ribu women refused to marry for political reasons. This was how they lived their politics in the day to day.

– what was the violence done to the Japanese Woman to hold her in this role as housewife … and what was the violence the Ribu wanted Japanese Women to unleash (For example, their campaigns in supporting women who murdered their husbands and children?)

The violence done to Japanese women to coerce them into this role operates as hegemony does in ways that obscure the very continuum of coercion and choice or lack thereof, these socio-cultural institutions that reproduce the gender normativity within families and schools in effect police people into their requisite gender roles. These processes are typically not recognized as violence but I think that the emergence of feminist and LGBTQ movements have made this form of social violence evident and demonstrates how it confines people versus allowing for gender liberation outside of the heteronormative binary.

Kogoroshi onna (mothers who killed their children) was a phenomena that uman ribu activists sought to reframe by highlighting the extreme form of alienation some women experienced from this kind of social-norming-as violence; these women rebelled against these norms and would even kill their own babies and children. I think that by highlighting their solidarity with such women, these activists were not condoning or praising such violence but were ready to acknowledge the potential violent power that each woman possessed but repressed until she was pushed to unleash it.

7. What legacies or imprints from the Ribu can we see within modern Japanese feminist discourse on sex, agency, and identity?

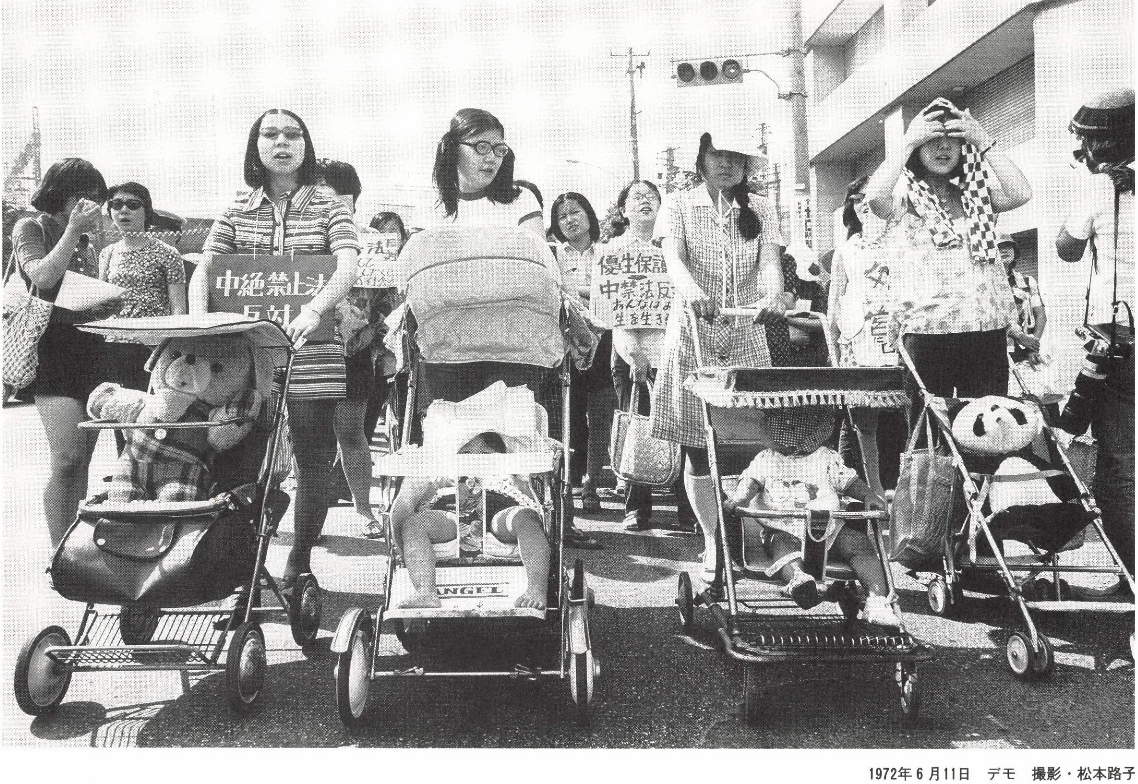

Japanese feminists have not emphasized the “right” to abortion, but the idea that we want to create a society where women want to give birth. In this kind of slogan, there was not a rejection of motherhood and women’s reproductive sexuality, but they wanted to create conditions whereby women could fulfill an authentic desire to fulfill these procreative capacities verses a social prescription that every woman must follow; they rejected the state imposed prescription of good housewife-wise mother (ryosai kenbo) which the state dictated women conform to.

8. I’m wondering if you could tease upon and elaborate on this quote and any contemporary relevance you think it may have for modern feminists or modern Neoliberalism.

Here it is clear that ribu women argued that the responsibility for child killing was not to be individualized—singling out an “individual before the law”—but was to be placed collectively on a society that makes a woman kill her child.

I think that we can understand this first quote to be a proto-feminist abolitionist approach to harm and wrongdoing. That its imperative to pursue the root of why and how harm is done. Rather than emphasizing individual responsibility as our neoliberal present-day society would have us focus on, I think that umn ribu shifts our perspective and analysis to the system that creates such oppressive and alienating conditions that would cause a woman to kill her own children.

9. Could you tease out the networks of support and solidarity between the URA and the Ribu movements? Why did they as feminists seek out solidarity with women of the URA who were otherwise vilified by Japanese Media and society?

9. Could you tease out the networks of support and solidarity between the URA and the Ribu movements? Why did they as feminists seek out solidarity with women of the URA who were otherwise vilified by Japanese Media and society?

Tanaka Mitsu and ribu activists had various affiliations with members of the Japanese Red Army and what became the United Red Army (not to be conflated with the international wing of the Japanese Red Army). There was a direct relational connection because Nagata Hiroko invited Tanaka and her ribu group to join the United Red Army in their training camp in the mountains. Given this invitation to merge, Tanaka wisely declined.

In addition to this specific historical-relational connection, there was also the philosophical and political dimensions of what was at stake in declaring solidarity with the women of the United Red Army. The philosophical and discursive intervention that Tanaka Mitsu made at this time in the early 1970s was that she (or any person) could be a Nagata Hiroko – that is a woman who sought to outdo other men and thereby impress others in a competitive society. Tanaka’s response sought to caution against the tendency to other others and think of oneself as fully capable of being the “bad guy,” the villain or criminal, and that such differences are largely contingent upon one’s life circumstance. She wasn’t promoting relativism in ethics, but she pushed for understanding the actions of the other.

The political aspect of this solidarity with the women of the United Red Army (URA) was also crucial because the state was using the URA as a means to vilify all leftist activism as dangerous and violent, magnifying the impact of a case of killing 12 activists (in an internal purge) as a reason to scare Japanese society away from accepting leftist activity as a legitimate. The URA was the ideal way to dismiss and delegitimize leftist activism by misogynistically blaming a woman for the militant and lethal violence that had already been symptomatic of the male-dominated culture of the New Left.

10. What lessons do you think the Ribu movement still has to teach the Modern Feminist movements in Japan?

10. What lessons do you think the Ribu movement still has to teach the Modern Feminist movements in Japan?

Their overall refusal to rely on or trust the Japanese state.

– What lessons does it have for international feminist movements?

– the importance of transnational solidarity and reflecting on how one’s relative privilege is based on these longer legacies entangled with imperialism, colonialism and racism.

– And in your own opinion, how can feminist movements better build international solidarity, both with feminist organizations globally, but also with leftist movements globally?

This is ideal, and necessary, but from my experience, its typically becomes circumvented by material constraints (24 hours in the day), lack of resources, but in today’s digital age, I think that communications among movements can take place quickly (even instantly) but trust and solidarity built on trust-and-action requires that slow(er)test of time- to be proven as sustainable, and ultimately, we want to build sustainable movements. Along these lines, I think that Women for Genuine Security provide a great model of a long term sustainable transnational feminist movement model.

11. And as an optional PS… the Uman Ribu were deeply committed to centering disabled activists and aware of how women’s appearance was often used to mute the validity of their words (both by the media, men and even other feminists).

The movement was fortunate to have Yonezu Tomoko as a central figure and as someone who was disabled from spinal cord paralysis her non-normative figure was a way to get visual attention, but the media always tried to manipulate images of her to mock the movement. Uman ribu’s understanding of how capitalism values the productive body to generate profit was connected to their analysis of the importance of valuing life and being outside of this value system of beauty and capital.

What messages or critiques would the Ribu have about beauty both in their time and its place in modern feminism or as a ‘dual- prison’ (Locking in and locking out) for women attempting to change society.

Ribu women on the whole rejected such trappings while creating their own new feminist aesthetics and redefining women’s beauty and strength. Their organizing of “Witch Concerts” in 1973-1974 would be an example of this kind of feminist arts and aesthetics. I think that feminists are always attempting to redefine and resignify what beauty means as part of a perpetual struggle against the locking in-locking out dynamic you describe. I suppose figures such as Ariana Miyamoto and Ikumi Yoshimatsu are among a new generation of women who participate in what are assumed to be anti-feminist practices such as beauty contests but attempt to use those platforms to challenge longstanding norms of Japanese racial identity and the male-domination in the entertainment industry respectively. This new generation of women challenge racialized notions of Japaneseness and expose the male supremacy and gendered violence within the entertainment industry which needs to be exposed. My concern is that we need to have a critique of neoliberal feminism(s) that celebrity feminism can often be complicit with so it would be interesting to dialogue among different generations of feminists to consider how anti-imperialism and anti-capitalism can continue to infuse contemporary feminisms in Japan.

For more on Setsu Shigematsu, please see her book here.

For more questions on Feminism, Japan, Stereotypes and travel, feel free to reach us at Matt@asiaarttours.com