This is the first of a 3 part interview w. Dr. Sho Konishi of Oxford on his stunning work for Harvard University Press – Anarchist Modernity: Cooperatism and Japanese-Russian Intellectual Relations in Modern Japan. Dr. Konishi was kind enough to send me an engaging reply that goes above and beyond our normal interviews. It’s honest, intellectually engaging and I think provides a great supplement to his book.

The work had a profound impact for me on how I think about Nations, The State, Anarchism and what a revolutionary and internationalist future might look like. I read quite a bit and it is, without a doubt one of the finest works of scholarships I’ve ever read.

You can read part 1 below. Here are Part 2 and part 3

1. For scholars, I’m always interested if there were formative life experiences which led them to pursue their specific field of study. Were there any events or figures which led you to research collaboration and translation between Japanese and Russian Anarchists?

Your question about life experiences is an interesting one. Our memories of life experiences often lead us unconsciously to (re)examine our world in a particular way. We are usually unable and unwilling to recognize this tendency, so we create narratives that allow us to live within such invented narratives. We tell stories that conveniently makes sense afterward, and which continue to change over time as we ourselves change. Our autobiographical narratives would appear to be the most accurate, but they are possibly the most inaccurate form of narrative. We’re all very good at pretending as if we know what led to what… We’re natural storytellers for our own psychological well-being. I guess our death-bound subjectivity leads to such creativity. So to respond honestly to your question, ‘I do not know’ is probably the most accurate answer.

Having said that, I imagine that my interest in Russia and Japan may have had something to do with my unhappiness with formal schooling in Japan back in the 1980’s when I grew up. I have almost no memories of my school life in Japan – it’s like a big blank in my mind, as if it had never happened, probably because I hated it. It became stronger as elementary school progressed. I still remember clearly when I asked in Year 7, which is when children began studying English as a requirement, why we were studying only one foreign language and why that had to be English. I failed to understand why English language should have so much power over us. The teacher answered that that’s the language required to get into high school. I responded, ‘If I don’t go to high school, then I don’t need to learn it?’ His response was that I was a bad influence on my classmates. I was asked to leave the classroom and stand outside. I got beat up by the teachers and had to stand outside the classroom, but none of this served to help me understand – in fact just the opposite.

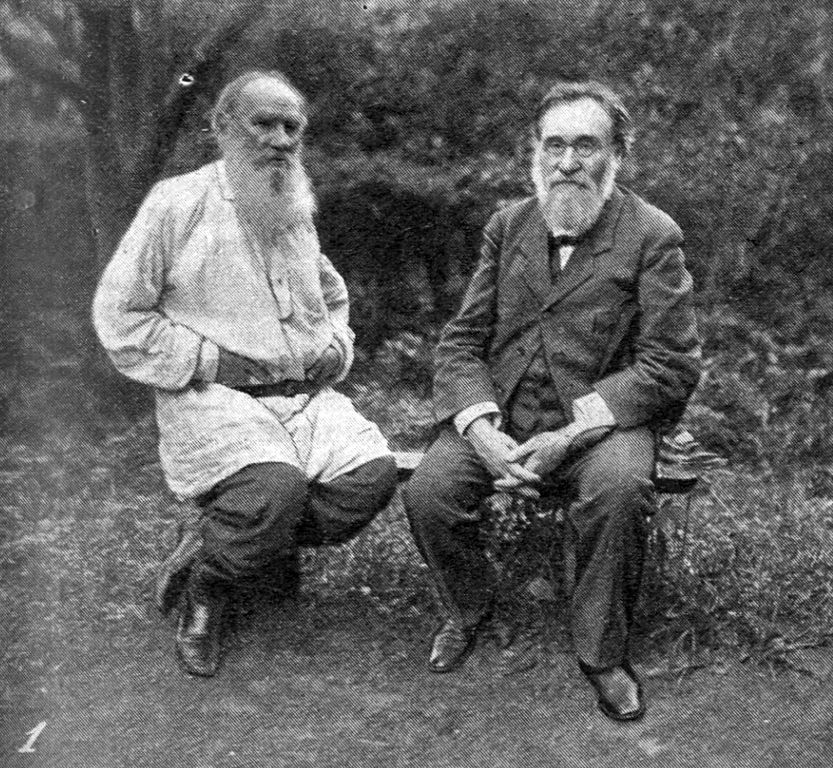

Tolstoy’s house and Museum in Russia

I began to realize that the problem was too large to solve in one classroom. Of course I threw away my English texts at the time. My schoolmates came to me with admiration and reverence for what I said and did – they agreed with me — yet they themselves did and changed nothing, fearful of saying anything and doing anything. It was as if nothing happened. The best students academically were the wisest, as they knew how to do well in such a system.

That was the pattern of my everyday school years. So I quit and became a school dropout, drinking by myself in the park from the morning, while my peers were preparing for their exams. My confrontation with modern state education had started much earlier, almost as soon as I was asked to go to school, but I won’t go on about that here. This sort of experience, and countless more, probably influenced how I saw the world, and played a part in what I wrote decades later. I was quite seriously concerned about that country’s future.

My early interest in Esperanto language (not that I studied it then) had something to do with this, for example, in that Esperanto is a kind of linguistic solution to all sorts of discrimination.

My interest in Russia was formed in this same way, because Russia was always so hidden in Japanese education. In Japan they never talked about the Soviet Union in school back then, as if it did not exist, or as if it were something bad and scary to talk about. If English had celebrity status, Russian was the opposite. So I ended up doing my undergraduate education in Russia.

Similarly, the military in Japan is always hidden from public sight and scrutiny. ‘The military does not exist in Japan,’ they used to say. So I became interested in military affairs precisely because of that. Of course, the requirement to study English has a lot to do with a longer and broader global history and, more immediately, Japan’s defeat in the Asia-Pacific war. This intertwining of the hidden presence of the Japanese military with the all pervasiveness of English language probably also had something to do with my becoming a cadet at a military university in the US, where I trained in military affairs while learning Chinese and Russian languages— remnants of the Cold War. This university possessed a highly rated Russian language program, including the best summer Russian program at the time. I ended up representing the US military school in the Russian/Soviet city of Tula, a military industrial complex that had just opened to foreigners the year I came. So I was ‘the first foreigner from the West’ (as Russians used to labeled me then) to enter that city since it was closed during the Soviet period.

Funnily enough, nearby Tula is also the Russian writer Lev Tolstoi’s estate home. I first encountered Tolstoi, who was to become an important part of my book, while I was living in Tula as an undergraduate. But it was not through the front gate of the Tolstoi Museum that I encountered him, but through a back way, when my Russian friends and I went to ‘gulyat’, walk around aimlessly to smoke and joke, to rest, or to swim in the same pond that Tolstoi used to swim in. The water looked filthy, smelly and green, but nevertheless… That was my first real encounter with Tolstoi – imagining him swimming in that pond on the estate neighboring the city that decades later would become a Soviet military industrial complex. When we did go to the Tolstoi house and museum for no particular reason, I did notice that his house had preserved a surprising number of books and letters in Japanese, which made me curious. Also, I realized then that the microbiologist Ilya Mechnikov and other scientists befriended him, despite his embrace of a pastoral, simple life of manual labor. I became curious about these people who were from such different backgrounds and professions, and yet appeared to be networked in multiple ways to one another, directly or indirectly. So yes, my curiosity was there then. But frankly, at that time, just to make my body move was tiring at the end of the Soviet regime. Especially being the first foreigner ‘from the West’ as a first-year undergraduate, without any family or friend connections, with endless shortages of everything, my primary focus was finding food to survive however I could — not scholarship.

(Tolstoy and Mechnikov )

Before my university studies, I had also become homeless for a good while in a number of countries. While I slept on the street, I was still holding on to my 9th-year school completion certificate as if that was going to help me. But quite the contrary, the certificate was of no value at all. I didn’t realize it then. While I slept on the street, I had many encounters with other homeless, as well as certain ‘tribes’ of outcastes (whether ethnic, racial, immigrant, social, intellectual or otherwise) in various countries. In the US, some of these ‘teachers’, as I used to consider them, were often the disposable and hurting veterans of America’s various wars. Some of them told me about America’s de-institutionalization policy, which released patients, many of whom were vets, from mental and other hospitals onto the streets. I am not an Americanist or sociologist and have no idea what led to all this homelessness among folks with war injuries in both mind and body. I have no idea if what they told me was true either. This type of experience, nevertheless, also helped lead to my interest in the problem of seeing like a state, not only in Japan, but internationally, creating a global if not transnational ‘underground’ world. On the streets of New Zealand, I encountered people of various ethnic and national backgrounds. I was wanted to learn more about what tied certain Maoris to the Malaysians, and Indians to others underground, with various ethnic and religious backgrounds, who made themselves invisible and escaped such national labels.

Ultimately, while homeless, I started speaking to God without an ‘o’ — not ‘God’ as a historical artifice, in the narrative sense, but Gxd without Being, without church, Bible, preacher, etc. It was just me and Gxd, always and everywhere, in an intimate relationship. I had lost utterance being alone there. I didn’t want to be a part of capitalist modernity (I didn’t call it as such then, it was more like ‘the money-centered empty culture of post-war Japan’ or some such expression I had), but to avoid being part of it had made me homeless. There was no one other than myself to justify my derailment. I felt then that if no one followed me, even if they agreed with me, then at least I should act alone. When you have no one else to talk to on the street, you naturally develop a conversation with Gxd about right and wrong. Without that experience, I probably couldn’t have thought about ‘anarchist religion’, a term that I invented, then discovered in historical reality, as a term to make sense of what was in fact there. Then I had to make sense of the space-time that had necessitated such an idea.

So this might have been an influence on my interests. It probably led me to be curious about the history of thought and practices that overturned the existing culture. My skepticism about any institutionalized knowledge that was in the interest of the state within the rigid departmentalization of modern institutions, and the accompanying politics of knowledge, all made me want to think outside them. Applying that to modern Japanese history many years later has at least partly led me to disclose anarchist modernity as a major cultural and intellectual current in Japan. All this is in hindsight of course. Until you asked me, I hadn’t thought about such links. But my attempt to create new approaches to study the history of modern Japan outside the fold of ‘West’-, Soviet- or Japan-centric historicity to make sense of the intellectual phenomena captured in my book, in hindsight had something to do with some of these ‘life experiences’.

(Dr. Konishi’s incredible book)

2. We’ll be discussing your incredible book today: Anarchist Modernity: Cooperatism and Japanese-Russian Intellectual Relations in Modern Japan

I notice throughout the book you highlight the impressive volume and diversity of places where cooperatist anarchism took root in Japan between 1860 and 1930: seminaries, hospitals, candy stores, farms, urban/rural poetry circles, prison camps and elite universities are just a few examples.

How were activists at that time able to transform multiple spaces (and communities) into sites of cooperatist anarchism? And what contemporary lessons does this offer for present-day individuals to also try and transform seemingly fixed (in meaning or function) spaces and communities?

Diversity and multiplicity are the very essence of anarchist thought itself, which reflects how these ideas develop out of the practical concerns of the everyday. That nature of multiplicity and everydayness in turn reflects on where and how they relate and communicate. Yes, space can be designated, fixed, and even controlled and managed by power, but what you think and do in these spaces at an undesignated time essentially determines the meaning of the space. Perhaps many of the actors didn’t intend to transform these places into something that they were not. It was in the process of putting their ideas into practice that came to give certain meanings to certain places.

For the most part, I don’t consider these spontaneous participants ‘activists’ per se. For instance, in the ‘people’s cafeteria’ Taishu Shokudo used by thousands of people in Tokyo at the time, customers were reminded with signs and other means that they were participating in the larger purpose of Sogofujo, mutual aid for global progress. Many of the actors I talk about would not even have identified themselves as ‘cooperatist anarchists’ per se. That’s probably why they were able to think and do what they did from outside the state-centric political sphere that revolved around civilization discourse. ‘Resistance’ was not a conceptual framework to fully make sense of their ideas. They had their own thought on progress that was simultaneous, but separate if not independent from Western civilization discourse — even as they lived with and often in it. It was beyond the modern bifurcation of colonizer and colonized. Theirs was a non-imperial thought that spread in a non-imperial way. That’s another reason why they couldn’t be identified then or now, through the investigations of neither the police at the time, nor many able historians’ many decades afterward. They were often just doing their everyday informal life practices that worked for them through mutual aid, with an ‘anarchist modern’ subjectivity that emphasized symbiosis with surrounding nature. They valued individual freedom and difference, mutual aid in time of crisis, as well as the beauty and virtue of conducting everyday life in everyday spaces. They saw and understood biological nature along the same lines. These ideas and practices circulated not only among public intellectuals, but also among ordinary folks, who believed that mutual aid was indeed the best function for survival even in the worst of times, times of pandemics, natural disaster, war and otherwise. It seemed that cooperation, not stark individualism and competition, was the most natural way of making their lives better.

Through these spaces, knowledge circulated in a multi-directional manner. Not from Tokyo or London to the rest, from city to countryside, or from ‘above’ to ‘below’. It is important not to believe that the origin of knowledge as coming from the ‘state’. In general, the state is usually many steps behind the reality, as everyone knows from everyday experience. So to talk about space, we have to talk about the direction of the process of knowledge formation. For anarchist modernity specifically, this circulation was often in reverse flow, even as it flowed in a multi-directional manner: from the countryside to the city, from the civil war losers of the north to the ‘winners’ of the war in the south, from Japan or Russia in this case to the West, and so on.

Disrupting the dominant direction of the formation of knowledge can serve to denature the hierarchical structure of knowledge. Multi-directional and even reverse flows of knowledge have stripped the power embedded in the circuits designed to propagate the state’s ideology.

There was a practical necessity of using different spaces for various learning functions. While imperial universities in Japan closely followed state guidance, cooperatist anarchists needed unofficial learning places. Imperial universities after all were far outnumbered by these unofficial learning places.

Imperial universities like Tokyo Imperial University wouldn’t teach anarchist thought. But on the formal chessboards that they created, an anarchist form of chess with its own rules and strategies was being played. So although spaces like state-run universities were controlled, historians have failed to look at what students actually did in those spaces that were designated for Western modernity. At night, in the dormitory, completely different activities that uprooted and challenged what was being taught during the day were taking place.

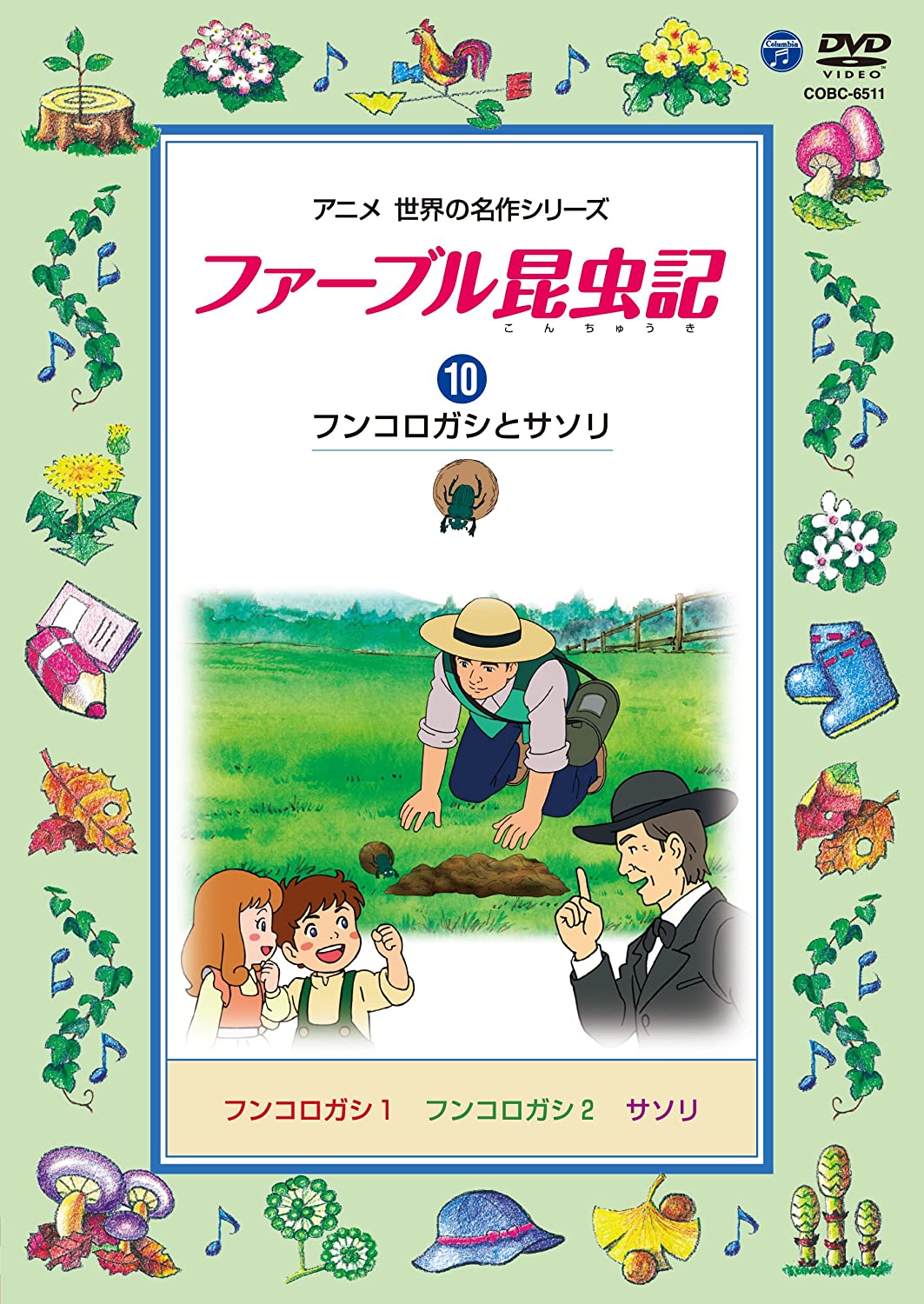

( Japanese Translator and Anarchist Osugi Sakae)

The seemingly mundane places where they developed their networks and the off-times when they practiced cooperatist anarchism have methodological implications. Your readers may understandably not be interested in research methodology per se. But it may be important to know that they acted outside our usual spheres of historical investigation, on the second floor of sweet shops, in hospitals, in people’s cafeterias, and in the evenings and weekends. They penetrated the interstices and passed through borders and other man-made barriers without discrimination, attaching themselves non-hierarchically to anyone along the way. As it spread, it transcended the states’ territorial borders, discarding class and occupational borders flexibly (although not so freely), and without discriminating gender, legal or financial power. And it did so through countless unexpected encounters and chance meetings. It acted a bit like an epidemic in this sense. The difference is that people in Japan did not fear or seek to avoid contraction. To encounter and absorb the ideas of cooperatist anarchism was to free oneself, to maximize one’s unique potential, and be given a place and opportunity to offer love and empathy in everyday life. What they encountered in cooperatist anarchism was often an articulation or an added value to their own existing cooperative practices. The ideas of cooperatist anarchist justified being active participants rather than backward, uncivilized and unvirtuous beings waiting to be directed by those with political, legal and financial power. In contemporary times (since that may be your readers’ foremost interest), it’s up to the reader to take different things from different aspects of the book to develop and apply as one wishes, like anarchist thought itself. But it does seem that we need such articulators occasionally who can give new meanings to people’s everyday practices. I hope the book has made a minor contribution to this end that will give new energy to ordinary folks and highlight their extraordinary potential through everyday practice, or to those who feel peripheralized in academia but who are working on incredibly innovative work.

Speaking of a lesson, sometimes the same person played dual roles in anarchist modernity, at different times of the day — like the Waseda University professor in the book who went out at night to join activities that contradicted what he was teaching at his university during the day. This may be another implication for us today in contemporary times, that you shouldn’t be afraid to do seemingly self-contradictory practices in this complex world. If you try too hard to unify everything in your life around a particular set of ideas, you could end up being homeless like me. If you feel like you are locked in, but you feel no other way to survive in this world, do something outside your ‘employed’ time that can be locked in by forces that you feel are outside your control. There are alternative times that belong to you, when you can create and belong to another temporality, and yet act in effective ways.

Paying attention to these odd places and times not only revealed how and where they were acting, but it also had methodological implications. A lesson for historians is to unlock these interlocked conceptions of historical knowledge production that connected sources, method, theory, and concept. This releases history from the fold of Western modernity, as well as currently popular ‘post-humanist’ positions that ironically often re-confirm modernity as a done deal.

Their connections also interconnected people of all walks of life. They themselves didn’t measure people according to class, gender, race, specialization, nationality, etc. And they easily connected in their minds what we now distinguish as the social sciences, humanities and natural sciences. This may be yet another lesson for contemporary knowledge production in modern higher educational institutions that neatly separate specializations and create their own territory and legitimacy, deep in their own wells. In the intellectual landscape of the anthroposcene, we should reflect and connect the social sciences and humanities with the natural sciences.

Entomologist Jean Henri Fabre’s work on the Dung Beetle, translated originally by anarchist Osugi Sakae

There was nothing strange, then, about early twentieth-century geographers drawing ideas from biology, or the White Birch School of literary people promoting Ilya Mechnikov’s microbiology and immunity. Ilya Mechnikov saw cells as symbiotically functioning in the inner core of our bodies, which helped lead to the idea of symbiogenesis. Nor was it odd that the anarchist Osugi Sakae translated the entomologist Jean Henri Fabre’s studies of the ‘lowly’ dung beetle. Osugi’s translation has become not only the most popular biology book of all time, together with Darwin’s On the Origin of Species, but also a sort of Mother Goose for Japanese children. Osugi created a nickname for one of Fabre’s favorite objects of study, the dung beetle, as ‘funkorogashi’, or ‘dung ball roller’. The dung beetle became extremely popular among Japanese children and adults alike, and remains to be so, even today. As I pointed out in the book, the dung beetle long outlasted the imperial ideologies that banned it. However, in academia, no one ever talked about this popular intellectual phenomenon, while focusing instead on the imperial ideologies that banned it.

Other instances include the most famed primatologist of Japan, Imanishi Kinji, who was a student of the philosopher Nishida Kitaro and what I called ‘anarchist sciences’ in the book. Imanishi did not look at primates as ‘nature’ separated from us, ‘civilization/culture’. Instead, he began to seek culture in nature, how empathy worked among primates, for instance. And the anarchist ethnographer Lev Mechnikov, who was a mentor for the natural scientist and anarchist Peter Kropotkin. Anarchists in Japan actively connected the humanities, social sciences, biology, philosophy, entomology, literature, ecology/environmental studies, agriculture, and Gxd/religion. The very thought that interconnected all those people of all walks of life on the street, interconnected the various ‘disciplines’ in which they became interested. That’s why literary circles meeting in places like the second floor of sweet shop studied about anarchist science and biology, and how to practice agriculture. Esperanto meetings become circles to study about the ecology and environment, concerns that are still very much associated with Esperanto language today in Japan. Places like local hospitals developed into anarchist meeting and publishing spaces. These various conversions of space occurred very naturally and unproblematically.

Urban spaces also turned into critical transnational spaces transcending borders, where people and ideas of various origins met. During the great Kanto Earthquake of 1923, key anarchist figures Osugi Sakae and his partner Ito Noe were brutally murdered by police terrorism. However, it was the thought and the multitudes of human beings that they left behind, as much as what they wrote and translated, that have survived until now.

The presence in history of such activities and the absence in our historical knowledge (historiography) are telling. It shows the nature of how and why history is often written and how it governs the future.

Historians often have defined ‘activists’ as those who engaged in the state’s political language. By so doing, these political actors determine their position by speaking the language of the civilizational discourse of the West. According to this measure, Asian societies have ‘weak civil societies’. However, we need to look outside Western modern vocabularies of ‘activists’ who speak the language of conventional state politics. Such studies of the weakness of political activism in the Nonwest inevitably revolve around state-centric and thus West-centric political history.

I don’t have quantitative evidence for this, but the Kanto Earthquake of 1923 was probably a major impetus as well for the weakening of the anarchist movement, because, while we are used to thinking of the ‘end’ or ‘weakening’ of anarchism by the events of the Russian Revolution and the rise of Bolshevism and Marxism in Japan, it was the natural and spatial destruction of Tokyo as hubs for these intricately formed networks that really helped lead to the displacement of anarchism – at least temporarily. The earthquake forced smaller hubs like the Shirakaba School to move out of Tokyo, dissolving the cooperatist anarchist networks that had formed at a time when spatial proximity was still essential for network formation. The police murdered two key leaders of the anarchist movement in the destructive aftermath of the earthquake, Osugi and Ito Noe, together with their young nephew, but it was the spatial dissolution of the earthquake itself, the disintegration of Tokyo’s sites as hubs of cooperatist anarchist networks, that most negatively interrupted this movement.

(Anarchist Ito Noe)

Many scholars search for feminism in Japanese history among figures who were part of anarchist modernity, like the above-mentioned anarchist Ito Noe. In their search for feminism, though, with almost no exception, scholars focus on suffrage as the measure and keyword of feminism and women’s history. However important this type of scholarship may have been and continue to be, it’s worth being cautious here as well. Once we make the Western version of suffrage-based feminism our measure and lens for examining Japanese ‘women’s’ history, then we miss a huge number of female historical actors who were very important, sometimes vital actors. These women were at the forefront of some of the most distinctive cultural and political movements in modern Japan. The history of environmentalism in Japan, for instance, cannot be discussed without consideration of the influential anti-pollution activism initiated, organized and led by ordinary Japanese housewives in the 1950s. The places where these ordinary housewives studied and practiced were their homes and backyards. Yet the fact that involvement in the national politics of the state was never a part of the women’s interest or ambition should not be considered a weakness. Our reliance on suffrage and conventional political participation as a social scientific yardstick of Western modernity has caused us to miss too many important female actors in Japanese history in the first place. Today, I imagine we could learn something new from the practice of these ordinary housewives that would allow us to change our very understanding of ‘democracy’, ‘civil society’ and ‘politics’ by looking at these least likely heroes of history.

One of my former DPhil students, Anna Schrade, has looked into ordinary housewives encountering mass pollution in the industrialization of Japan, during its economic expansion in the immediate postwar. These ordinary women initiated and conducted extraordinary scientific studies by collaborating with scientists. They gathered evidence from and studied their mundane everyday surroundings to demonstrate inhumane pollution levels. They collected dust and tested the air and water around them under the motto of sogo fujo, mutual aid, when the government and the corporations weren’t acting. Their counter network to state and capitalist modernity spread horizontally, transcending age, occupational and class differences. Indeed, those differences were the key to the success of their counter network. They also made their own amateur documentary of the local pollution that was eventually shown nationwide on the national broadcasting channel. Spontaneously organized and networked on the grassroots level, these women were very much an example of anarchist democracy in postwar Japan that made fundamental differences in their own lives. The implications of producing a historical account of their activities are not small. Until now, we have looked at the global 1960s and ‘70s, by focusing on male elites initiating an environmental movement, with an assumption that knowledge spread from ‘above’ to ‘below’. We are finding exactly the opposite; that we have overlooked the housewives of the ‘40s and ‘50s, women who didn’t believe in or simply didn’t give a damn about voting. The media and then elite male intellectuals followed these women’s initiation of postwar environmentalism only much later. Only then did some elites begin to join when it was already safe to do so, because it had become acceptable to talk about these things in the 1970s. Our historical accounts have only paid attention to these elites. At a time when the men were employed by the polluting industries and often fully contributing to environmental disaster, their wives were acting the other way around in the same household, by going against the polluting activities of their own husbands and their employers’ — without any violence. Women throughout the world should be encouraged to act without the state, and anarchist modernity has shown just how much one they have made difference, and will continue to be so.

Speaking of space, when counter networks form against domination, segregation, and power, what shape do they take? Here we can take a cue from nature on the molecular level and from the ancient art of basket weaving. Bamboo weaving practices are being looked at by Jo McCallum as a contact point between humans and nature. We can view effective and long lasting networks as kagome, a pattern used in Japanese bamboo weaving. The method of bamboo weaving takes into account the natural form, grain, and coloring of each individual piece in the weave, making the baskets strong and yet pliable. Physicists have used the term kagome as a name for a particular formation of lattice discovered as occurring naturally on the molecular level. Kagome lattices now form the basis for cutting-edge research in highly conductive manmade materials likely to be useful for the quantum computers of the future. We can similarly view the development of strong, pliable and highly conductive social networks by using the metaphor of kagome.

Part 2 and 3 of the interview are published: Part 2 and part 3. For Dr. Konishi’s incredible scholarship, please see his book Anarchist Modernity: Cooperatism and Japanese-Russian Intellectual Relations in Modern Japan by Harvard University Press