Asia Art Tours recently visited Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia and spoke with renowned Photographer Ian Teh. The first images you’ll see (in sequence 1-8) are from Ian’s series, TRACES:darkclouds. Images 9-11 are from his series: Confluence. All captions are Mr. Teh’s.

Our discussion revolves around Ian’s work photographing climate change and carbon emissions. For more w. Ian, visit his site here: ianteh.com

Tailings from a steel plant. A retired truck driver from the area tells me, “Nothing made here stays heres. Our government has exported our blue skies to the West.” Wuhai, Inner Mongolia, China. 2010

Asia Art Tours: How did you first come into Photography, and was this encouraged by your family ? Did you have any formative experiences as a young man which led you to this profession?

Ian Teh: There were three key points that brought me to photography. The first was the dawning recognition in my 20s that photography could influence the world for the better. This was epitomised by my formative heroes like Eugene Smith, who documented communities devastated by industrial mercury poisoning in Minamata, Japan. He was instrumental in highlighting the issue and effecting positive change. The second was the idea that photography could be, in a philosophical sense, a way of life for the learning and enrichment of oneself. Cartier Bresson expressed this eloquently and his words were an inspiration to me for a long time, “To take photographs means to recognize—simultaneously and within a fraction of a second—both the fact itself and the rigorous organisation of visually perceived forms that give it meaning. It is putting one’s head, one’s eye, and one’s heart on the same axis.” At that time I was in search for a code to live by and this with its undertones of Zen (which I was also exploring via books) was intensely appealing. The third, was my physical and emotional response to photographs that moved me, it was similar to my reactions to drawings, my earliest obsession. A line expressed perfectly or a photograph imbued with atmosphere always felt the same — it hurt. The pain was an expression of longing to know intimately what it feels like to have been the creator of such beauty. As for familial encouragement, my father being a typical Asian parent was always worried about my life choices. On the other hand, my mother, despite coming from the same country was always much more outward looking and forward thinking, she wanted me to pursue earnestly what made me happy.

Friends I admired and respected, and people I met within the industry formed some of my most formative experiences. One such person was Neil Burgess, he had been a director at Magnum Photos in London; when I met him, he had just set out to be an independent agent representing photographers like Sebastio Salgado and Annie Leibovitz. He was generous with his time, spending a good couple of hours patiently looking through my college portfolio. He then showed me contact sheets from Salgado and Lebovitz, giants in photography even at that time. That first meeting and a subsequent one (after I made my first trip to China) over a year later when he was a director of the highly regarded Network Photo Agency, became conversations I would reflect on for many years after and in essence was a compass to help me navigate my practice and career. I don’t think he was ever really aware how much that meeting had meant to me at that time, but he helped me realise how much bigger the photography world was and at the same time highlighted some of the qualities I would need to develop to have a chance of succeeding. Most of what he said was in many ways just common sense but it wasn’t common to me at the time; he helped simplify in that moment the seemingly overwhelming task of getting started in a career of photography by helping me concentrate on the essentials.

Kuye River is a subsidiary to the Yellow River. 80 percent of the land in this region is made up of coal deposits. Due to overmining the water table has sunk and the river that was once full of water is now nearly dry. The city now wealthy from decades of coal mining now regularly suffers from water shortages. Yulin, Shaanxi, China. 2010

AAT: What are the challenges of being a working photographer, both in terms of real world (making money, growing your audience?) and ideals (How do you make sure that you get assignments for the stories you want to tell?)

Ian T: I started this career because of the ideals photography represented for me. The reality of being a working photographer means there is often a balancing act. However I would still emphasise that it is vital that most of what you do should be meaningful to you beyond just paying the rent. All of these small acts and decisions isn’t just our work history, it is a legacy that we build. And it works in both directions, meaning that the work we chose to do is also the kind of work that is most likely to find you back. A potential client is always going to choose you based on your past, so its always a good policy to do stuff that you care about.

A make shift screening machinery that is built at the bottom of a river bed that is now nearly dry due to overmining in the area. Industrious entrepreneurs have exploited this misfortune by digging up the rocks in the area and selling it for construction. Yulin, Shaanxi, China. 2010

AAT: How has your work changed your philosophy of the world? In particular how has your view of capitalism and its relation to the environment evolved over time?

Ian T: I have nothing against capitalism per say, but I prefer a more democratic and socially minded model of capitalism. I would also like capitalism to be truly accountable in the widest sense. It should include the often hidden costs to the environment, and the cost to retire or recycle a product once it has reached the end of its useful life so as to minimise its environmental impact. None of the goods we buy today is valued at its true cost. There’s a term for that type of accounting, its called: true cost accounting.

Ian Teh: A cement plant on the grounds of a large steel factory on the outskirts of the city. Linfen, Shanxi, China. 2010

AAT: Can you tell us about your work in China? What drew you into documenting the use of coal, and does your work in China have any global implications in terms of climate change or the anthropocene?

Ian T: My work is about China as much as it is about every other country that continues to develop, especially when its using fossil fuels. It is about the price we pay to fulfil our material desires. And China is the biggest development story this century, achieving levels of industrialisation and development on a scale that the world has not witnessed before. It has lifted 800 million of its citizens out of poverty through economic reforms first put in place in 1978 by Deng Xiao Peng, but at the same time rampant development with lax environmental controls has taken a heavy toll on the environment and the health of the Chinese. Even today the impacts of that cost is still being felt and will continue for many years to come.

Today the most polluted cities in the world are in India, as China has slipped to second place after its efforts to clean up its practices domestically. When I started work on these issues in China I felt that the country was soon to reach its tipping point, where the true cost of its development will eventually come home to roost. I wanted my work to be a cause for reflection as to what it costs for us to live the life we desire. Whilst today, this has become an environmental reality we face in many parts of the world it is also encouraging to see a growing global movement challenging our politicians and industry to change our current course of living.

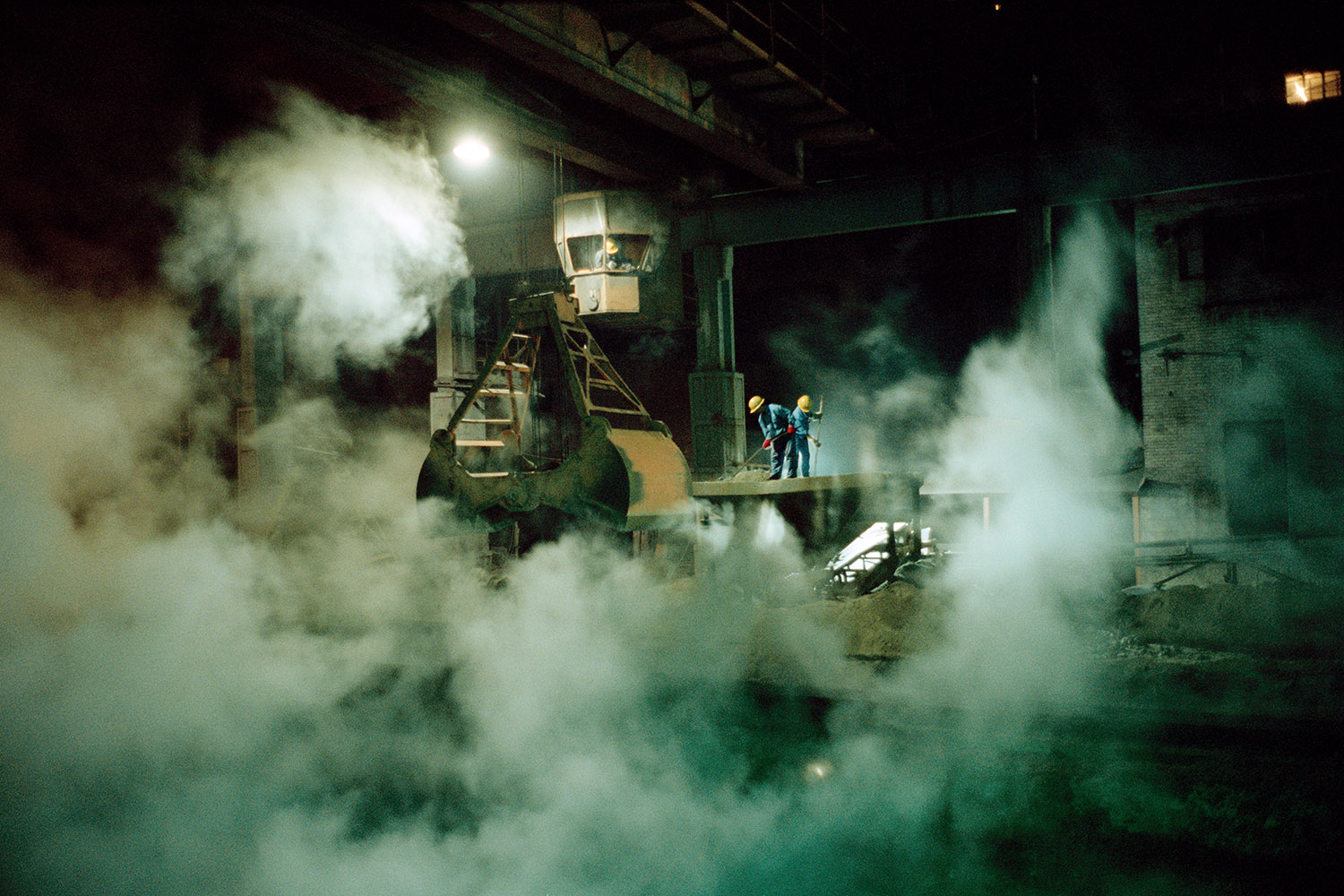

Workers at a steel plant working at a limestone pit. Steel is a common material used in range of products in everyday life and China is the number one producer of steel in the world with their production of steel presently on the increase. On a global context the manufacturing of steel, every hour of every day over 13,000 pounds of toxic chemicals are released into the air, water, and land, and dust particles and greenhouse gases are released into the atmosphere. Each hour, 70,000 pounds of total waste is generated, all of which requires treatment, recycling, or disposal (1996 figures). In 2006 China exceeded the US as the number one emitter of CO2. Tonghua, Jilin Province, China. 2006

AAT: For the images that you’ve captured on photography, what are some of the questions you want the audience to ask? And what are the questions driving you for future projects?

Ian T: My projects are often about dreams and the cost it takes to realise them. I want people to reflect on the way they live their lives, how what is happening afar, seemingly unrelated is actually really closely connected to us. As a global society this awareness has to be at the forefront of our minds first before we can truly be motivated to make the political changes needed for a more sustainable future. Climate change is one of the key challenges of today, and I shall continue to explore its many related issues within my work.

An employee from a coal mine plays pool late in the night after work. Many workers in the coal industry come from farming communities in the countryside, driven by poverty they leave their homes to seek jobs in the coal industry. Tai Yuan, Shanxi, China. 2006.

AAT: When you make photography how do you determine who the audience is? Do you have an audience in mind? And are there any tensions in the world of photography between trying to cultivate a large following online, and the small world of elite (wealthy, upper-class) buyers for prints or owners of galleries?

Ian T: My primary concern is usually the story and the issues I’m interested in. I don’t necessarily ‘determine’ my audience but I am aware of the kind of audience I am attempting to engage. Collectors of my work are often long time followers of my work. Sometimes there are collectors who choose my work after having seen a particular image published. At other times there are institutions and museums who acquire my work in part because of the nature of the issues I am engaged with. I think, for me, it’s probably best to concentrate on the things I can control: my objectives and my creative approach.

Worker in a small coal mine. China is the largest coal user in the world, it also claims the most unenviable record, that of the highest number of coal miners with lung problems. Black lung disease is the result of the lungs being coated with coal dust as miners work at the coal-face hacking out the coal, or elsewhere shifting the lumps of coal or mining waste. The name, black lung, comes from the distinctive blue-black marbling of the lung from the coal dust accumulation. This disease occurs mostly in those who mine hard coal (anthracite), but also occurs among those mining soft coals and graphite. After about ten to twenty years of exposure, symptoms to set in and it may be aggravated by silica (causing silicosis) mixed with the coal. Shanxi, China. 2006.

AAT: For projects like that of investigating coal in China, what are the technical/artistic challenges of trying to tell a story based on process/current events in a static (unchanging) medium like photography? if the story is ongoing/evolving, how can a photograph capture this process and its after-effects?

Ian T: The creative challenge for me is to inject something other than the reporting of a story. Often that comes about from deciding what my intentions are creatively. For my series Dark Clouds, my purpose wasn’t just to document the working conditions of workers within the industry. My perception and interpretation of the subject was fundamental to how I would eventually portray my subject. I saw a dream of a nation, not only the state’s ambition for global recognition, but the individual dreams of the many migrant workers who helped build today’s China. They were cogs, and their desire for a better life meant leaving poorly paid farming jobs for better paid but often more dangerous industrial jobs.

This transaction and motivation, mixed together with an abundance of coal helped propel the country forward. The immense scale of this nationwide operation was turning the countryside and its towns into some of the richest and sadly the filthiest. The cost was the environment and the people’s health, and it was these interconnected themes that occupied me. Creatively that meant I would translate these ideas and realities into an impressionistic set of images; choosing to photograph these laboured industrial scenes as a dark dream, heavy with a sense of the full impending costs still to be paid.

Flames shoot out of a coking plant as coal is being burnt to create coke. Much of the machinery in these plants are old and that do not have new technologies fitted to lower the levels of pollution coming from these plants. Coking plant. A recent study from the World Bank found out that 750,000 die prematurely in China each year, mainly from air pollution in large cities. China’s emissions had not been expected to overtake those from the US, formerly the biggest polluter, for several years but according to figures released recently in 2007 by the Netherlands Environmental Assessment Agency, which advises the Dutch government, soaring demand for coal to generate electricity and a surge in heavy industries such as steel and cement production has helped to push China’s recorded emissions for 2006 beyond those of the US. However per capita China is still far behind the US and Europe with each person averaging a carbon footpint of 4 tons a year. Benxi, China. 2007

AAT: Do you see photography as benefiting from social media that emphasizes image and sharing? Or do you worry that by having so many images available to us (On Instagram, FB, Twitter) that it makes it impossible to focus on the most important stories, or the stories told by experts?

Ian T: I think its a mixed bag of advantages and disadvantages. There are definitely advantages to sharing the work on social media, as a way to draw an audience to the actual published story online or in print. It is also a way to stay actively connected with followers of your work.

Ships Passing. Straits of Malacca.The Straits of Malacca is a narrow, 805 km stretch of water between Peninsular Malaysia and the Indonesian island of Sumatra. From an economic perspective, it is one of the most important shipping lanes in the world. Historically, this strategic position brought trade and foreign influences that fundamentally determined Malaysia’s history. The strait is the main shipping channel between the Indian Ocean and the Pacific Ocean, linking major Asian economies such as India, China, Japan and South Korea. One-quarter of the world’s traded goods including oil, are shipped through these waters.$$$

AAT: Lastly, what future projects are you looking forward to investigating and what message if any would you like to emphasize about your past work?

Coastline. Straits of Malacca, Malaysia.Malaysia’s ethnic and cultural makeup is largely due to several centuries of migration resulting from its uniquely important position as a maritime trading hub. Hindu and Buddhist cultures imported from India dominated early Malaysian history for centuries. Although Muslims passed through Malaysia as early as the 10th century, it was not until the 14th and 15th centuries that Islam first established itself on the Malay Peninsula. The adoption of Islam by the 15th century saw the rise of a number of sultanates. Trade with China and India during this period saw the first Chinese and Indians settling and adopting aspects of the Malay culture into their own. The descendants of these early ancestors are today’s Baba-Nyonya and Chetti community.The Portuguese were the first European colonial powers to establish themselves in Malaysia in 1511, followed by the Dutch. However, it was the British who ultimately secured their hegemony across the territory. The Anglo-Dutch Treaty of 1824 defined the boundaries between British Malaya and the Netherlands East Indies which then became Indonesia. A fourth phase of influence was the immigration of Chinese and Indian workers to meet the needs of the colonial economy created by the British in the Malay Peninsula and Borneo.$$$

Ian T: For the foreseeable future, I will continue to engage with stories that relate to the environment and China. I’m currently working on my long term series on the Yellow River, Traces: Landscapes in Transition in the Yellow River Basin. They are panoramic photographs of landscapes undergoing forces that affect it, but are rarely apparent to the eye, because perhaps, strangely we tend to view landscapes as static. The timeline of how land changes is different from how we as humans perceive those changes. The transformation of the Yellow River is not just a product of recent economic reform. By exploring the Yellow River’s place in Chinese culture and history and China’s emergence as a major economic power, I seek resonance with romantic notions of the past and present. The search is for a gentle beauty, but also for muted signs of a landscape in throes of transition. It is the dissonance between these bucolic yet ambivalent scenes, set against historical, economic and scientific narratives accompanying them that I find significant. Through these explorations I hope to connect viewers to the front lines of climate change, where the environmental crisis underway, isn’t always easy to see.

Westport. Port Klang, Selangor, Malaysia.

Port Klang is the main gateway by sea into Malaysia. Colonially known as Port Swettenham, it is the largest port in the country. It is located about 6 kilometres southwest of the town of Klang, and 38 kilometres southwest of Kuala Lumpur.$$$

Ian Teh’s work has been published internationally in magazines such as National Geographic, The New Yorker, Bloomberg Businessweek and Granta. Since 2013, he has exhibited as well as conducted masterclasses at Obscura Festival of Photography, Malaysia’s foremost photo festival. He is a tutor at Cambodia’s Angkor Photo Festival since 2014.