To better understand the conservative nature of Black celebrities in our revolutionary now, I spoke to Cassie da Costa (New Yorker, Daily Beast and Vanity Fair).

Cassie pens the sharpest writing I’ve encountered on how most Black Celebrities in America too often work against the abolitionist demands of the Black Lives Matter Protests. Part 1 of our conversation is below.

Asia Art Tours: Despite any attempts to make superheros ‘woke’, their form remains that of the cop. A cop who enforces the traditional order of the colonial world, in other words, private property and capital. In this era of global protests, where we’re seeing individuals cosplay in protests as Spiderman and Captain America, do you think the manufacture and media of Superheros will change?

Cassie Da Costa: I don’t think it will change soon or very much. Superheroes are, financially and ideologically, the lifeblood of Hollywood. But it is possible that, in the narratives we receive, these Superheroes will begin to have different fundamental political interests, or that the villains they’re meant to keep at bay will start to take on more and more radical beliefs, particularly as we dive into a new kind of McCarthy era where antifa and even race scholars are being targeted as dangerous people by the government. We saw in Black Panther how the villain, played by Michael B. Jordan, believed in a militant approach to Black liberation. So many critiques of that film coming from the left pointed out that the villain in this film had the more generous politics; the hero, in fact, was upholding and protecting empire, and that was plain to see. I’m not sure if that will translate to protests, where people aren’t merely going to dawn a costume that espouses their specific set of beliefs, but one that perhaps communicates something to their adversaries: “No, I’m the good guy.”

At the same time, we even have people on the left handwringing about rioting, looting, militant non-electoral approaches to changing things. So, it’s not just the mainstream or status quo that is upholding the superhero myth, but even some of the people who believe themselves to be thoroughly critical of it. People’s politics often unwittingly reflect the fantasies media feeds to them, about what and who is worth protecting, for instance.

We saw in Black Panther how the villain, played by Michael B. Jordan, believed in a militant approach to Black liberation. So many critiques of that film coming from the left pointed out that the villain in this film had the more generous politics; the hero, in fact, was upholding and protecting empire, and that was plain to see.

Asia Art Tours: With the death of Chadwick Boseman, who truly seemed like a nice man, I wanted to do a brief retrospective on his character “Black Panther”. In an era of mass protest for black lives, why do you feel so many Americans (of all races) felt so connected to this character?

Cassie da Costa: Well, I think there are two levels to this. One is that we’ve already had Will Smith, this mostly family friendly, universally beloved entertainer and then we had Obama, who also served as this super-likeable Black figure to certainly not all, but a large swath of Americans—large enough, anyway. T’Challa, then, offers a palatable liberal vision of Black authority that has already been in the making through decades of mythologizing about the civil rights movement. How much whitewashing and romanticization of that era have we had to hear, in media, in textbooks, in films even including documentaries?

At John Lewis’s funeral, you have Bill Clinton slipping in a dig about Kwame Ture (formerly Stokely Carmichael); in that moment, he’s selling a false narrative that a lot of people will accept on its face, that Lewis and Ture were fundamentally opposed, the former a hero and the latter a villain. Of course, Lewis had respect for what his more militant brothers and sisters were trying to achieve, even though he came from a different tradition. Martin Luther King Jr. himself began to see more eye to eye with the socialists towards the end of his life (which really just should have been the middle of his life). No matter what you think about it, politicians and media have spun nonviolence into this kind of meek, solely electorally focused approach when it wasn’t. So, for a long time, the foundations of this character T’Challa have been built by a dominant narrative; why else would Marvel make this film? T’Challa is a mascot in the same way that MLK and even John Lewis were made into mascots, figures or symbols for the public to hold up as an uncomplicated mirror.

At the same time, people connect with the character because the particular kind of goodness they see in T’Challa feels connected to their hopes for their own goodness right now (and the same goes for MLK, Lewis, and Obama). If you don’t think too hard about the film’s underlying ideas, it offers a lot of comfort and perhaps even courage to people who may feel at a loss during an especially cynical, ugly time for the general population. Patriarchy is meant to be a comfort, and if you can see that kind of comfort in a Black man, then, the thinking probably goes, it means that you have access to the goodness that figure represents.

So, for a long time, the foundations of this character T’Challa have been built by a dominant narrative; why else would Marvel make this film? T’Challa is a mascot in the same way that MLK and even John Lewis were made into mascots, figures or symbols for the public to hold up as an uncomplicated mirror.

Asia Art Tours: And in remembering Mr. Boseman, what conflict of narrative may emerge between how the Public wants to remember Mr. Boseman as a Black Activist, and how the Disney Corporation may try to control his memory as a Black Superhero?

Cassie da Costa: That’s a difficult question. My instinct is that there will not really be much of a conflict in narrative because, unwittingly, so much of the way the Black Activist has been deified in a segment of the media is dependent on corporatism. This is to say, what, today, is an activist? I’m not sure I would call Mr. Boseman one, and that’s not at all a criticism of him. I think he was a representative, and a wonderful actor, but I’m not sure if his good deeds, advocacy, or philanthropy would amount to any kind of anti-corporate activism, as such. But again, I think a lot of Black advocates have happily participated in corporatism. I think perhaps the only major counter to this right now might be how John Boyega has worked hard to contradict Disney’s marketing of him in the Star Wars films—his words offer a kind of roadmap for culture and entertainment writers to understand this kind of thing.

Obviously, though, once Disney has you in their clutches, particularly in the context of a premature and very private death, they’ll use their machinery to make money off of a simplification or distortion of your image. I’m sure the executives there were disappointed that Carrie Fisher lived at least long enough to write her own memoirs and to establish herself beyond the container of Princess Leia. Unfortunately, Boseman didn’t have that privilege, so we’ll see.

But again, I think a lot of Black advocates have happily participated in corporatism. I think perhaps the only major counter to this right now might be how John Boyega has worked hard to contradict Disney’s marketing of him in the Star Wars films—his words offer a kind of roadmap for culture and entertainment writers to understand this kind of thing.

Asia Art Tours: I think it’s very interesting that after Ryan Coogler directed Black Panther, his next project was the 60s era Biopic – ‘Judas and the Black Messiah’ of Real Life Black Panther, Fred Hampton. I wanted to ask if the screen depiction of Fred Hampton is counter-revolutionary in ways that might not be obvious but important to discuss?

Cassie da Costa: I don’t think it would be by definition but it’s very possible it will be in practice. It’s a big Hollywood production with famous actors and an industry-approved director. If Black Panther gives us any indication of what Coogler will do going forward, the film could very well end up overriding radical ideas with liberal praxis. Plus, the tendency of the biopic fiction film format to reify icon narratives (just look at the film’s title) is in itself counter-revolutionary. We’ll see.

What I was interested in, as a Black American critic, was not only the question of, is this project appropriation or not? Is this project capitalizing off of the continent or not? I was most interested in critical viewpoints on Black Is King as a work of art… did it actually offer something fresh formally, aesthetically?

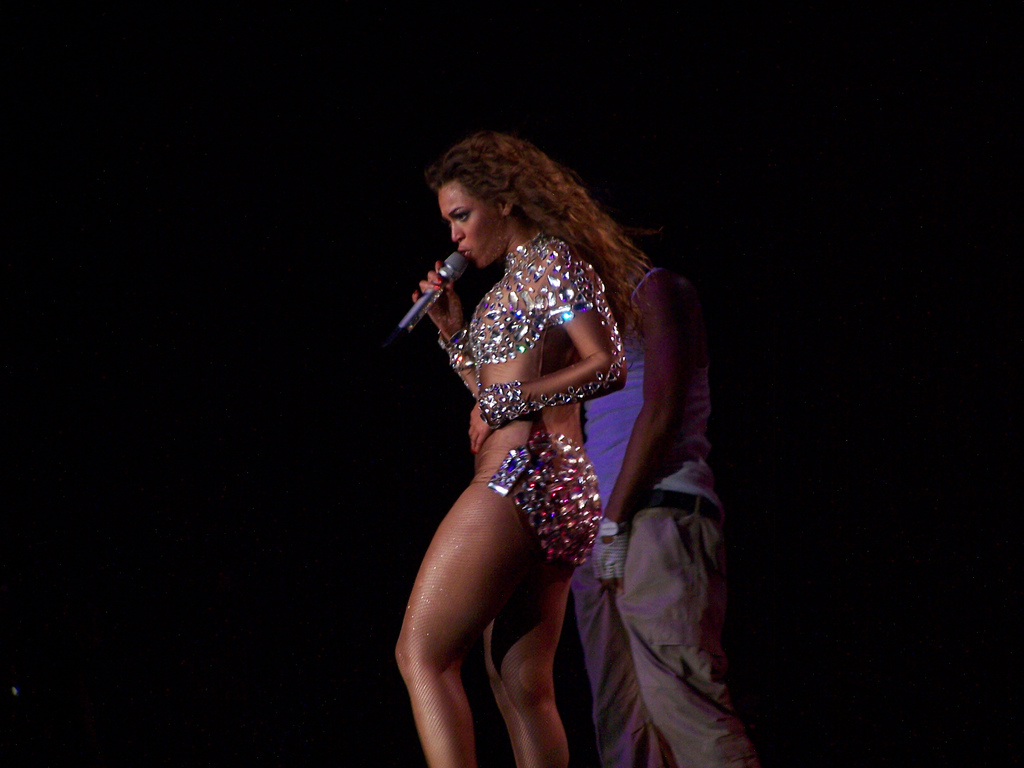

Asia Art Tours: Lastly, I wanted to touch upon Beyonce. You wrote a fascinating column asking why ‘no one is willing to criticize Beyonce’, and in particular her affinity for hierarchy, wealth and deeming herself royalty? I wanted to ask, in the broadest possible way, do you think we should be criticizing Beyonce? And if so, what conclusions did you arrive (either in your column or upon further reflection) as to why she receives no criticism?

Cassie da Costa: Obviously, Beyoncé has received more scrutiny in the past and, as I mentioned in the column, Rachel Kaadzi Ghansah published a profile of her fans, the Beyhive, in NPR years ago that was also critical of the star. In my column, I’m pointing out an increasing trend of passivity towards her, collectively in American criticism, that I think is a result of her incredible power in the industry and how it’s kind of built around this representational politics. It’s very hard for writers without the backing of major outlets (that hire very little, and don’t necessarily pay freelancers very well) to say anything sharply critical of her without feeling like they’re either exposing themselves to online harassment or damaging their potential to get coveted jobs in the industry. And then those writers who already work for the major outlets, of which I am about to be one, it seems that a lot of their criticism is heavily qualified, careful. That’s fine—there’s plenty of room for that sort of work; but I was lamenting that this environment has the effect of making more mischievous voices rarer to find.

I saw some criticism of the piece that pointed out the African writers had been very critical of Black Is King, though in the piece I’m very clear that I’m talking about American reviewing. This is key because while Beyonce stages the project as an African one, and on the continent, she is an American artist and very much a product of this country’s Black culture(s). I’m not surprised that more African writers would write more frankly about the project and would (perhaps, though I don’t actually know) feel less fearful of doing so. There are certainly very different cultures around criticism in most places outside the U.S. (I draw a comparison to the U.K. in the column, via a column written by Clive James). But what I was interested in, as a Black American critic, was not only the question of, is this project appropriation or not? Is this project capitalizing off of the continent or not? (Worthy questions that African as well as American commentators discussed thoughtfully before and after the video was released.) I was most interested in critical viewpoints on Black Is King as a work of art… did it actually offer something fresh formally, aesthetically? A lot of what I read skirted around this question to instead do close readings. I don’t think this approach to first round reviewing (versus codas or academic texts) is common with artists of lesser stature in the industry.

A notable exception is Armond White, a Black and gay and, in many ways, conservative critic who is actually a lot of fun to read even if you disagree with the core of his politics (which I do). His review of the project (which came out after I filed) was scathing, though very honest for him. It’s obvious to anyone who has read his work that he wasn’t panning Black Is King for clicks or controversy, but because it really was an assault to his senses and worldview. I’m sure he wasn’t the only Black American critic who felt this way (in fact I know it), and in many ways the media industry—particularly prestige media—is failing the public by rewarding evenhandedness over and above verve. And this, again, isn’t to criticize writers who dig deep and publish very thought-through analyses that don’t seem to bring the hammer down on either end; it is to say that, surely, there isn’t a consensus that Black Is King was the best thing ever (and as someone who reviews a lot of movies I know that even when things are 100% fresh on Rotten Tomatoes or whatever, there are critics who hated the film), so why aren’t we hearing about it? I offer some of my own ideas about why in the column about why this happens—for Beyonce specifically and sometimes in general—but I ultimately think it comes down to how compelling representational politics can be, not only to the greater public or to writers but to those in power.

For more of Cassie’s work, follow her on Twitter or in her new role at Vanity Fair. Part 2 pf our conversation w. Cassie will be out in the next month!