The sheer amount of lectures, books and podcasts coming from Left spaces can be daunting. Fortunately, a new generation of artists are presenting progressive ideas in engaging visual ways.

I spoke to Lizartistry on her work turning the words of the Left into visual aids and how art can help us visualize our revolutionary futures. I hope you enjoy our conversation and check out more of Lizartistry’s work!

Asia Art Tours: In numerous global protests and freedom struggles this year, visual art and culture has been extremely important. To start could you tell us a bit about your own project, and how you’ve been fueled or inspired by the revolutionary symbols that have emerged from global movements? (Three fingers, Milk Tea Alliance, Murals for George Floyd, Revolutionary graffiti)

Lizartistry: I’m still in the process of identifying what “my project” is. The short story though, is that I really enjoy “visually appealing” (for lack of a better term) notes, and started to make some of my own about topics that I found interesting. Being in the U.S., and probably other factors as well, the social movement imagery I’m most often exposed to are the portraits of victims of police shootings. Beautiful and powerful portraits of George Floyd and Breonna Taylor circulated widely last summer and were involved in what were some of the largest protests in the country’s history. I’ve felt a lot of inspiration from these images in the way they lift up specific people and their lives while helping to mobilize thousands of people to the streets. At the same time, there is something about the attention to someone’s life only after their death, as well as the focus on a single life, that I feel uneasy about.

It’s obviously not this simple; for example, the murals for George Floyd represent more than George Floyd’s life. But in any case, when I read an article about the protest art flooding the streets of Yangon, I felt so excited to see the generative imagery that reflected a growing, dynamic movement in real time. These weren’t just portraits of Aung San Suu Kyi (which are also out there and problematic for a number of reasons, perhaps most notably the ongoing genocide of Rohingya people). The three-finger salute doesn’t point to any single leader and instead represents the defiance and strength of the people. I started looking up protest art from Myanmar and this also led me to art that had come out of the protests in Hong Kong.

These illustrations featured protestors themselves, and not just one or two, but crowds of them. One of the most inspiring elements of the Hong Kong protests, in addition to the creativity of tactics, were the sheer numbers of people involved, and these images captured both! I don’t know how widely circulated these images were compared to Myanmar. But I would absolutely love to see symbolic or crowd imagery come to have more of a prominent space in movement art in the U.S. and this has inspired me to create some of my own, and in turn, producing “art” images has also started to influence how I illustrate graphic notes as well.

Someone might not be down with the idea of abolishing cops, but seeing an illustration of a community gardening, cooking, and eating together can be more inviting and approachable to start a conversation about what community safety might look like.

Asia Art Tours: To dig a bit further into the how and why of your project, could you discuss how you choose the topics that you illustrate? Is there a common theme(s) or philosophy(s) that you are trying to highlight? And how has your artistic process allowed you (or your audience) to find deeper connections to these texts and lectures?

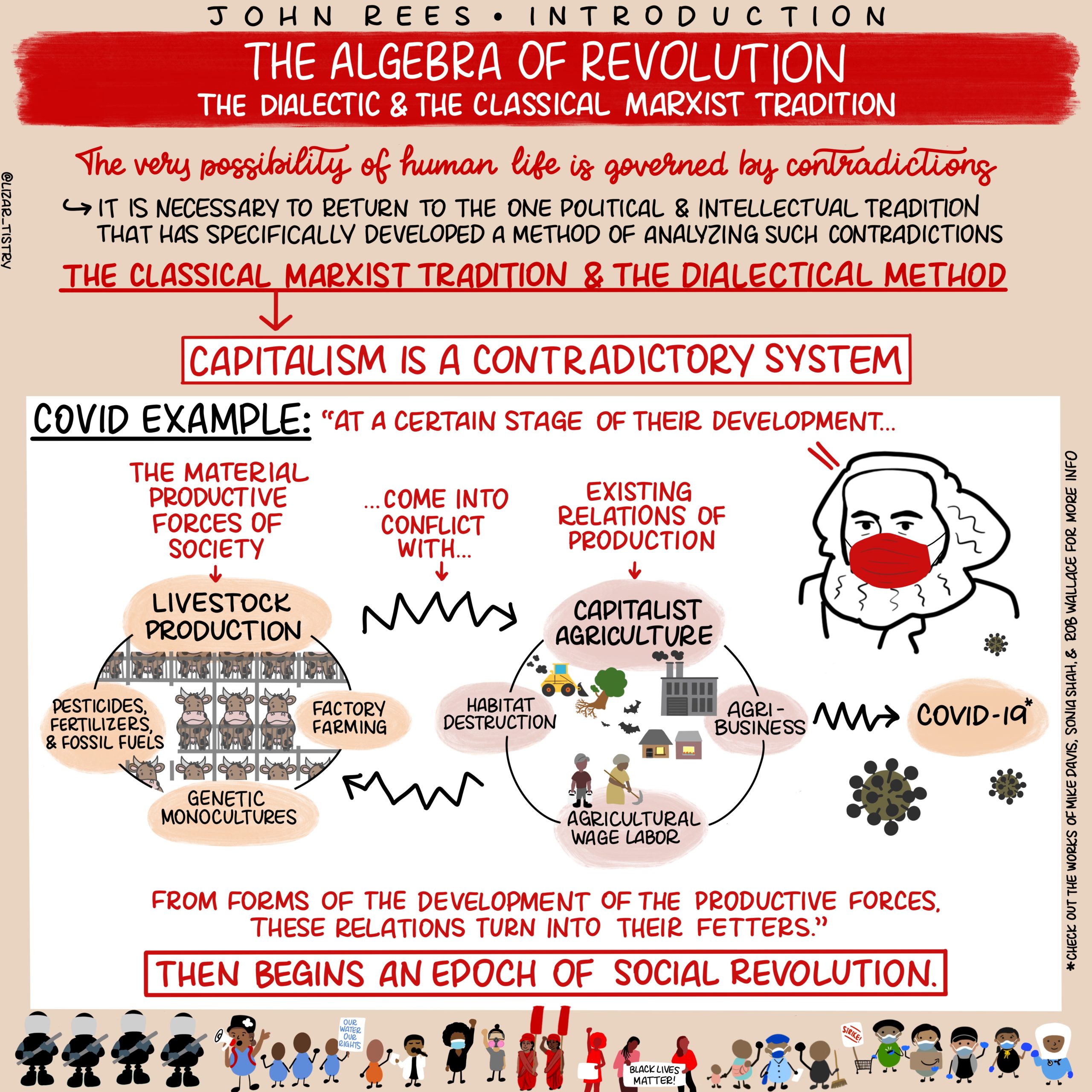

Lizartistry: I would love to do more images about Marxist theory and application. I find that every time I read or have a conversation about it, I learn to see the world in an increasingly more nuanced and dynamic way that feels really beautiful. I’ve done a few of these images, but, as I’ve learned from Marx’s dialectics, art isn’t just the product but the process, and process is made up of relationships. I began creating graphic notes partially as a way to still interact with this material, while feeling zero capacity to engage offline. Engaging in an artistic practice though has really opened up space for me to seek out relationships with people again because otherwise the process feels dry, static, and lonely, even inauthentic. It’s slow, but I can feel it happening.

Something I hope I’ve been at least somewhat successful at is sharing a wide range of topics, although admittedly from a narrow set of perspectives, which are international, abolitionist, and/or socialist. This is based on my frustration in seeing how “socialist” and “social” movements often operate so separately and sometimes even antagonistically (though not always!), and wanting to bridge them. Unfortunately, I haven’t been able to hone any sort of strategy around this, but I’m hoping that as I continue to build relationships with people, this will start to come together more fully. It all feels abstract and new still, but very exciting too!

I would love to do more images about Marxist theory and application. I find that every time I read or have a conversation about it, I learn to see the world in an increasingly more nuanced and dynamic way that feels really beautiful. I’ve done a few of these images, but, as I’ve learned from Marx’s dialectics, art isn’t just the product but the process, and process is made up of relationships.

Asia Art Tours: Left critique is necessary, but often has to address massive and amorphous concepts (such as: Neoliberalism, global capitalism, nationalism, Climate Change, ethnosupremacy). I think this is partly why many leftists gravitate towards singular enemies they can visualize (Bezos, Epstein, Gates, Trump, Biden) and struggle speaking with nuance on more abstract topics.

When you picture the ‘enemies’ we must defeat, how do you see illustration as giving ‘flesh’ to the brilliant theories, critiques and ideologies that you cover? How does illustration help us better ‘see’ beyond the wicked individuals involved in these ‘evil’ structures, and help flesh out the structures themselves?

Lizartistry: I definitely struggle with how to depict amorphous and abstract concepts in my graphic notes, and even more so, the dialectical relationships between them and their material conditions. Infographics are very mechanistic, classifying and ordering things for easier readability. Simplifying complex ideas is great to make them more accessible, but there eventually needs to be deeper analysis. On the other hand, I think that illustration can be really powerful in depicting the complexity of ideas.

I know very little about art and art history, but Diego Rivera immediately comes to mind as an example of this. My partner has a print of “Man at the Crossroads” in our living room. The mural centers around an industrial worker, flanked by capitalism, or “The Frontier of Material Development” on one side, and socialism, or “The Frontier of Ethical Evolution” on the other. I think the imagery does an incredible job of giving “flesh” to an anti-capitalist critique. But what is even more exciting to me is the history of the painting itself and the controversy around its production, from the Rockefellers commissioning Rivera to paint it in the first place, to Rivera and his crew refusing to remove Lenin’s face from the mural, to the protests and boycotts that emerged in solidarity with their refusal. The history to me shows the complex relationship between content and production in art, and, most importantly in my opinion, the ways this can manifest itself in collective struggle.

I felt so excited to see the generative imagery that reflected a growing, dynamic movement in real time. These weren’t just portraits of Aung San Suu Kyi (which are also out there and problematic for a number of reasons, perhaps most notably the ongoing genocide of Rohingya people). The three-finger salute doesn’t point to any single leader and instead represents the defiance and strength of the people.

Asia Art Tours: On the other hand, how do you see illustration helping us better visualize our (anarchist, abolitionist, socialist) utopias? And how does it allow us to do so in a way that words alone cannot? How does illustration (yours or generally speaking) better help us see the blueprints we need to save the world? (or build a new one?)

Lizartistry: The graphic notes I create have a lot of words, so I don’t think they’re a good example. But generally speaking, I think that abolitionist art, such as @kahyangni, @itsmonicatrinidad, and @jessxsnow, offers beautiful visualizations of collective safety and liberation. What feels most powerful for me, as I mentioned above, is the art that depicts the movement moments happening in real time, and here I’m thinking again of the art that has come out of and depicts on-the-ground struggles in Hong Kong and Myanmar. Some of the art from Hong Kong includes both beautiful representations of protest while also incorporating the “We are water” concept with depictions of fluidity and water itself.

From abolitionist art to crowd art depicting street protests, I think this imagery can be very powerful in mobilizing people around our struggles, which is important when thinking about building mass movements. Someone might not be down with the idea of abolishing cops, but seeing an illustration of a community gardening, cooking, and eating together can be more inviting and approachable to start a conversation about what community safety might look like.

Abolitionist praxis provides a lot of easily accessible avenues for people to start deconstructing toxic ideologies in their personal lives, from engaging in transformative justice processes to starting mutual aid projects, and I think this is part of what makes it so appealing.

Asia Art Tours: To conclude, Edward Ongweso Jr. discussed with me how all these toxic ideologies (in particular White Supremacy and Capitalism) have ‘poisoned our imaginations’. We’ve talked quite a bit about creating educational materials through illustration for leftism. But you and I are just humble writers and artists with infinitesimal budgets compared to the trillions of dollars capitalists, corporations and governments can pour into their toxic ideologies.

How do we resist the visual propaganda of these toxic ideologies? How do we ‘detox’ our imagination to try again and see the world (and the world we want to build) with our own eyes?

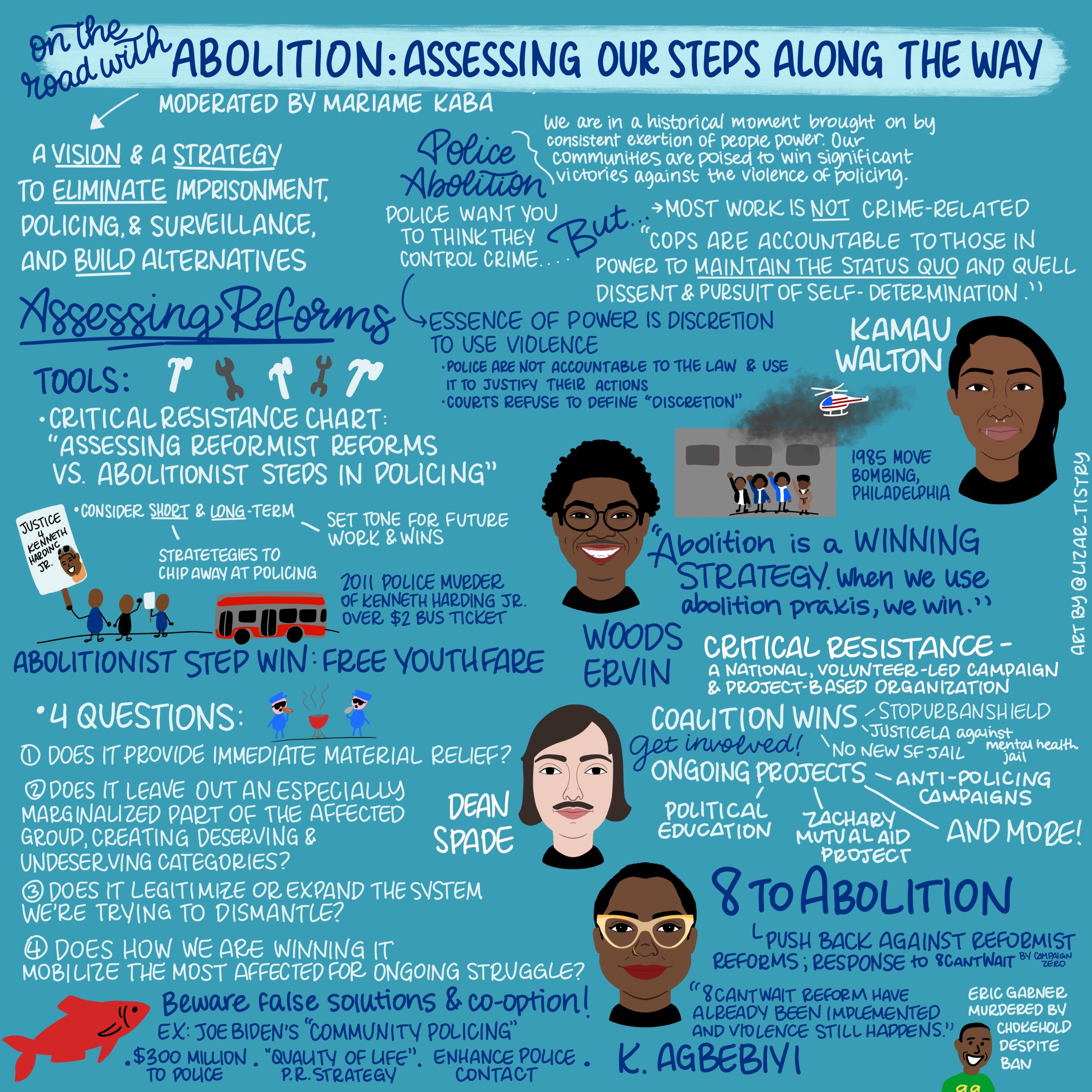

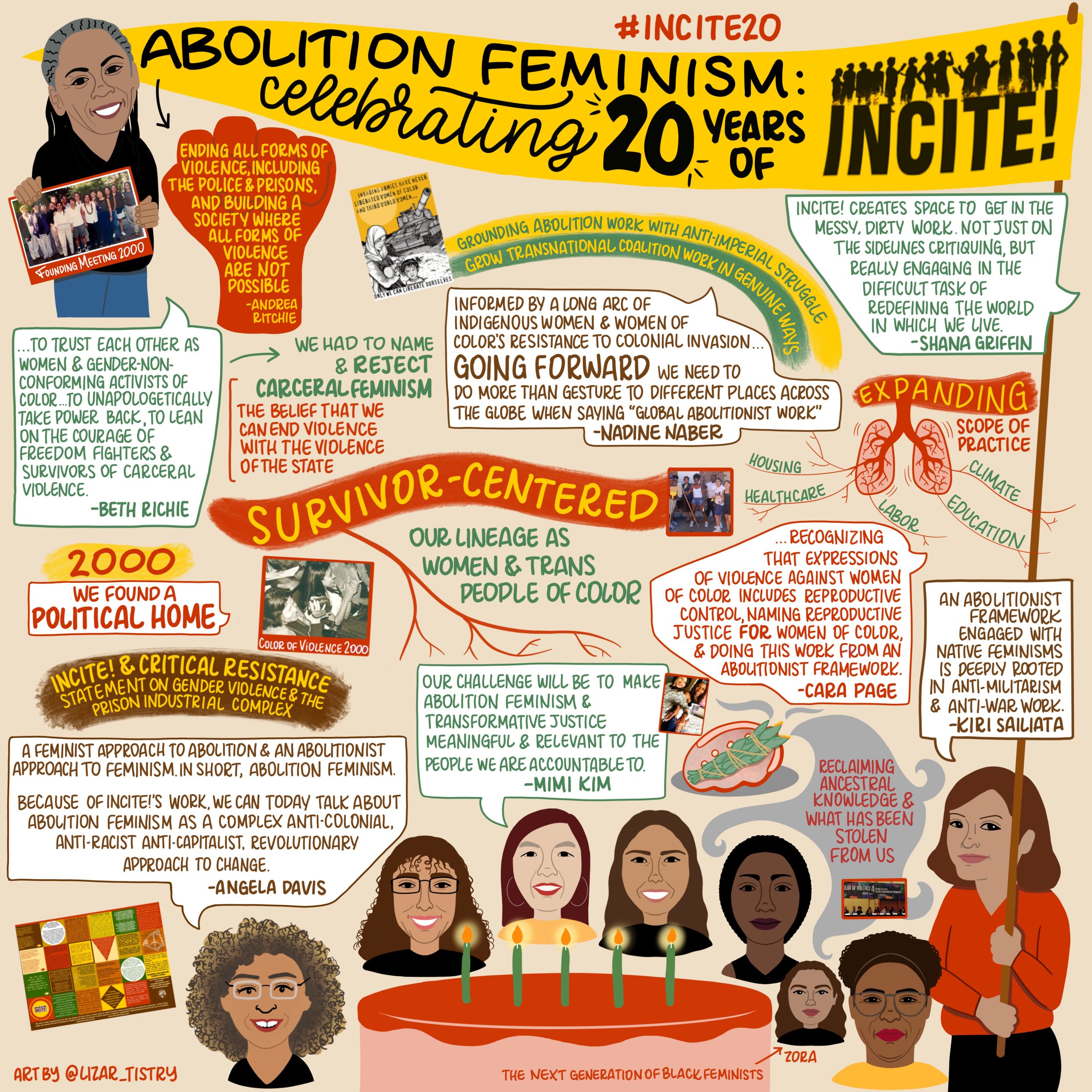

Lizartistry: I think educational materials can play an important role in struggle, but need to be part of a larger strategy. In terms of considering “toxic ideologies,” and I apologize because my answer is very U.S.-centric, but I think that there is a lot to learn from how abolitionist organizers, especially Black feminists, laid the groundwork so that when the George Floyd protests rose up last summer, thousands if not millions of people rallied behind #DefundThePolice. Abolitionist praxis provides a lot of easily accessible avenues for people to start deconstructing toxic ideologies in their personal lives, from engaging in transformative justice processes to starting mutual aid projects, and I think this is part of what makes it so appealing. Educational materials, like Critical Resistance’s updated “Reformist Reforms vs. Abolitionist Reforms” guide, can be invaluable resources.

At the same time, I think abolition has its limits. We saw this when many of the same people shouting to “Defund the Police” in the streets last summer, were also the same people demanding the conviction of George Floyd’s killer cop and increased hate crime legislation. These are contradictions that abolition recognizes and holds, but for which it does not seem to have a convincing solution. I agree with abolitionists who respond to this by saying that it makes no sense to expect a solution when our communities receive next to nothing in resources and funding. But then how do we actually take power and control of the resources and funding that are stolen from us, beyond building pockets of community control and safety with the little we’re left with? This goes back to a larger strategy that I think has to emphasize, if not center, how the working class has a unique and pivotal role in seizing power given the material conditions of production under capitalism. While class struggle offers a revolutionary strategy, in my opinion, it still needs the sort of space offered by abolition that builds transformative, accountable relationships, as well as our capacities to navigate arising contradictions between the toxic ideologies we’ve internalized and the dreams for which we’re fighting.

Black feminist socialists have led the way in expanding the horizons of this overlap, and the Combahee River Collective’s statement stands out as an example although maybe not explicitly abolitionist. But it was also written at a time when the labor movement was a lot stronger and before neoliberalism co-opted so much of its innovative and radical language and concepts, such as “identity politics” and “solidarity.” Today I think there’s a new opportunity to learn from the black radical feminist tradition in its original socialist framework and the abolitionist feminists continuing this tradition. In terms of how we do this, I think Edward Ongweso Jr. said it really well in your podcast – constant engagement.

All images are provided courtesy of the artist, do not share images without permission. For more w. Lizartistry, be sure to check out her Instagram: Instagram.com/lizar_tistry/