As Armenian and Jewish founders of Asia Art Tours, we are keenly aware of the pain and suffering of Genocide. Right now, the genocide in Xinjiang is one of the most urgent crises the world must face.

To shine light on this mass atrocity, I spoke to the founder of the Xinjiang Victim Database, and Uyghur Pulse – Gene Bunin. Gene’s platforms are essential in documenting the Genocide of Xinjiang.

Asia Art Tours: For people who are unfamiliar with your work, could you discuss Uyghur Pulse, the Xinjiang Victims Database and Shabit.biz? What are the objectives of these projects? And what obstacles have you faced in trying to continue to bring attention to these issues?

Gene Bunin: The Xinjiang Victims Database is a multi-purpose web platform based at shahit.biz. Like the name suggests, it’s a database of victims linked to China’s northwestern Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region, which over the past 3-4 years has seen a drastic rise in the incarcerations of the largely Muslim, mostly Turkic ethnic minorities who live there – the Uyghur, Kazakh, Kyrgyz, Hui, Uzbek, Tatar, etc. What shahit.biz does is document these people in as much detail as possible, one by one and publicly. At the moment, we have close to 10000 people documented, the majority of whom are in concentration camps (the ones the media has covered thoroughly), jails, or police custody, with a smaller but significant portion in less coercive, softer detention forms (e.g., children whose parents have been detained, or people with residence abroad whose documents were confiscated and can’t leave).

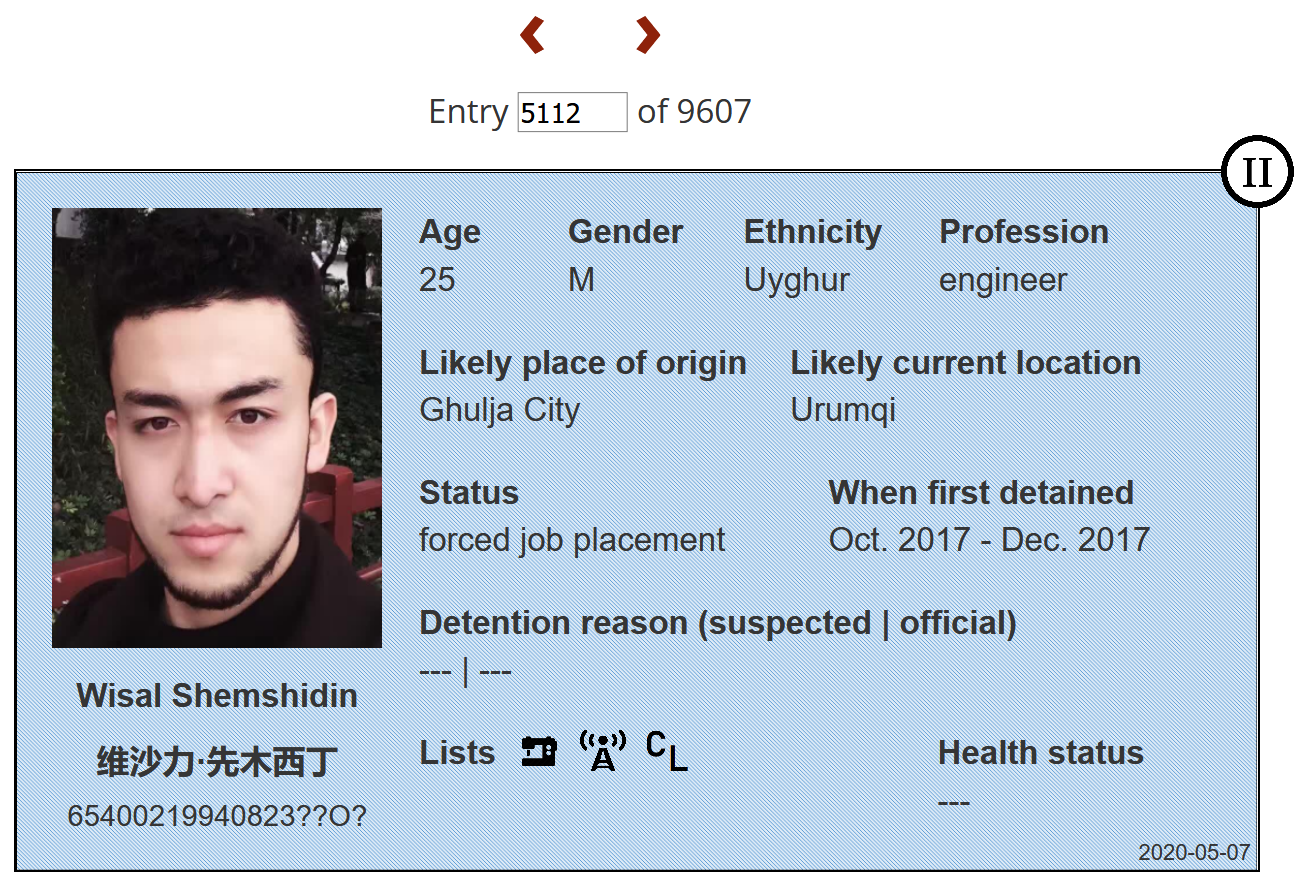

(Screenshot from the Xinjiang Victim Database – Entry 5112 – Wisal Shemshidin. Read more about his abduction and how it was verified here:https://www.shahit.biz/eng/viewentry.php?entryno=5112)

(Screenshot from the Xinjiang Victim Database – Entry 5112 – Wisal Shemshidin. Read more about his abduction and how it was verified here:https://www.shahit.biz/eng/viewentry.php?entryno=5112)

When this was launched in September 2018, the purpose was a bit abstract. A lot of people were starting to publicly speak up about their relatives back then, to the point where it was no longer possible to give media coverage to everyone who did (I was collaborating with media outlets at that time), and so some sort of repository where absolutely everyone could have their place was needed. There was, of course, the long-term documentation value – some people posted their stories on social media, got lots of attention, but were forgotten a week later.

There was also my personal conviction that more people needed to speak up, because we were all in this prisoner’s dilemma, where the Chinese authorities would almost certainly be in trouble if everyone – we’re talking thousands of people at least – spoke up together, but where getting everyone to do so was extremely difficult, as few wanted to be the first and most feared that they’d be the only ones, and that this would result in their relatives back home being punished. By creating a platform where you could see everyone else’s testimonies, we thus made it possible for people to overcome these doubts and fears to different extents (e.g., some people who might only speak up when hundreds of others have could do that once they saw our numbers).

Over the past two years, these goals have evolved. To some extent, we’ve become a very analytical platform, which is not really the goal but a very positive side-benefit, as you can use our data to study different patterns, trends, and nuances, and a lot of things become apparent that would not be apparent otherwise. Also, as that critical mass of people ready to speak up has been largely reached, we’ve shifted less from encouraging new submissions and focusing more on the victims we have – refining their entries, doing additional research on them, and rating them in terms of evidential value (i.e., what you could take to court). I guess you could say that we’ve shifted more towards quality over quantity. We also think of ourselves as a monitor, and strongly encourage the Chinese authorities to think of us this way also – if something happens to one of our documented victims, we will learn about it sooner or later, and the relevant parties will be held responsible. So, they should just keep that in mind when they torture-interrogate someone or give someone a 15-year sentence.

(An Example of a Uyghur Pulse Testimonial. Here Tumaris testifies for her father, Yalqun Rozi (shahit.biz/?f=yalqun-rozi), and asks for your help signing the change.org petition for him: https://www.change.org/p/pen-america-…. )

For Uyghur Pulse, I’ll be brief as it’s really a much smaller side-project. Basically, for people not super familiar with the issue – in 2018 and 2019, there was a group in Kazakhstan called “Atajurt” that was critical to getting this issue to the point where it is today. This was a grassroots non-registered organization of a few dozen Kazakhs who basically went around the country, often to villages, and encouraged people – often farmers, who were not cosmopolitan or tech-savvy – to speak up about their detained relatives in Xinjiang. They arranged interviews with international media, helped people write petitions to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, and helped people record thousands of video appeals, which they all made public on their YouTube channel. In short, they empowered a lot of people and, as it turned out, this helped create such a stir that – as we now know – concentration camp guards started going into cells in Xinjiang on around December 23-24, 2018 and asking who had connections to Kazakhstan, and then releasing these people. Hundreds, maybe thousands, even returned from Xinjiang to Kazakhstan. And this was a grassroots movement, without a lot of money and actually persecuted by their own government, who managed to help accomplish all this. It remains an unmatched success.

My goal in starting Uyghur Pulse was to try and replicate what they had done for the Kazakhs in Kazakhstan, but internationally for the Uyghurs. Unlike the Kazakhs, the Uyghurs don’t have their own country or a place in the world where they could easily get together and speak up – they’re just sort of scattered everywhere. However, we live in the age of the internet and the education level of the typical Uyghur abroad is far higher than that of the typical Kazakh farmer. So, in that sense, Uyghur Pulse was an experiment to replicate the video testimonies that Atajurt really pioneered – to have Uyghurs from all over the world submit videos for their relatives and to have them all put up on a single YouTube channel. The modus operandi is that we collect a monthly batch of 50-100, throw them all on YouTube, and then post them on Twitter/Facebook daily, to create a “pulse”. The individual videos don’t need to be groundbreaking and they don’t even need to be good (though of course that helps) – the main purpose is to create this background noise of real people speaking that just doesn’t go away and keeps this issue “alive”. And to get more and more people to join, of course.

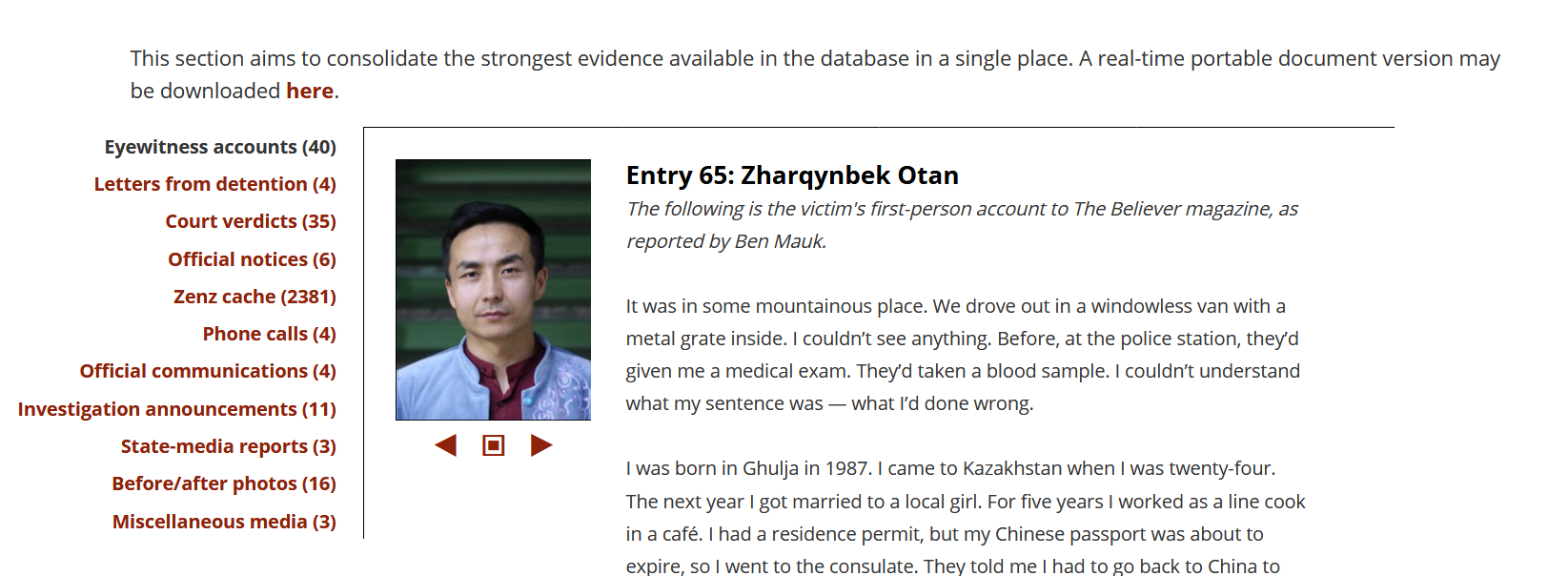

(Screenshot of the ‘Primary Evidence’ section of the Xinjiang Victim’s Database: https://www.shahit.biz/eng/#evidence)

(Screenshot of the ‘Primary Evidence’ section of the Xinjiang Victim’s Database: https://www.shahit.biz/eng/#evidence)

All that said, people are risk averse by nature, and this has probably been the most difficult challenge in all of this. What I always try to get across to people – both people from Xinjiang and foreign nationals – is that the situation has changed radically from 2-3 years ago. Speaking about a victim and making their story public has, as shown over and over again, been much more likely to help them than make things worse. That probably wasn’t true some years ago, but today I feel like being quiet is just silly – the ice has been broken in a very major way and the Chinese authorities seem to know that local intimidation is unlikely to work and may just end up bringing even more negative attention. This is one of the things that we’ve discovered in doing all this, and so it still drives me nuts when people whose relatives are interned choose to remain silent or those who had been outspoken before suddenly vanish because their relatives have been taken out of incarceration and placed under some form of house arrest or local surveillance. Speaking for one’s relatives is low-cost, powerful, and non-political, so more people really should do it.

The other difficulty has been data sharing. As a rule, we make all of our data public and encourage others to do the same. Unfortunately, I cannot say the same for certain scholars and media outlets, who in recent years have obtained incredibly valuable information but do not share – neither with us nor with the interested community at large. This is harmful on a purely mechanical level, as it limits the tools available to us and the others working on this issue, sometimes very significantly.

AAT: We always respect those who ‘do the work’ in their advocacy, which means learning the language and centering themselves in local knowledge and people. For individuals interested in your projects could you discuss a bit about both how personally have centered yourself in this cause through your language learning, centering yourself in local research and so on?

GB: I got involved with Xinjiang very accidentally, as a traveler, and then spent a year there for fun (2008-2009). As I was into languages at the time, I started learning Uyghur. After the July 5 incident in 2009 – for which I was, for better or worse, not present – I decided, perhaps naively, to contribute to this oppressed ethnic group by creating language resources for other outsiders who wanted to learn their language. That started a decade-long book project that is still not done and is currently on hold, with everything that’s happening.

(Children in Kashgar, looking out at looming buildings , pre-genocide. Photo Credit- Gene Bunin)

That being said, I was never super political and generally tried to “play it safe”. I didn’t pursue conversations with locals about the political repressions – more likely, I avoided them – and I tried to maintain a balanced opinion of the Chinese government (attributing their poor policy decisions to stupidity as opposed to misguided totalitarian intent). I can’t say that I formed a ton of close relationships either – in part because I feared that the language book I was working on might be seen as sensitive someday and that this would get people I knew in trouble. Instead, I took a very “bit torrent” approach to learning the language, where I would have very many superficial relationships and very many simple discussions, learning the language from the masses without getting too, too close to any specific person. (In retrospect, given what I’m doing today, I’m actually very glad that I did this – though now I earn to be able to return to the region one day and have the kind of heart-to-heart discussions that I’d previously avoid.)

2017 forced a lot of people to change course though, and when you live there – inside that police-state pressure cooker, where people you know disappear and people you knew start acting weird – it becomes very difficult to take it all in without suffering some sort of trauma. Sadly, the only thing I did for a long time was talk and write about it, and it was only in late 2018 that I really went full-time. It would have been good if I started shahit.biz a year earlier – although, at the same time, few of us really understood how serious this was all going to be then (that started to happen in 2018).

(Pigeons in front of Kashgar’s Id Kah Mosque, pre-genocide. Photo Credit – Gene Bunin)

AAT: and for those who may want to seed or start projects in the same vein as yours, could you discuss both the level of verification and the verification process you use for any and all information you post to your projects? What does it mean in terms of time and effort to ‘do the work’ to ensure accuracy?

GB: The basic caveat that I always put forward is that no testimony is fact, and that their strength is essentially in their numbers. To that extent, I invite people to turn on their analytical thinking and look for those patterns that appear over and over and over, and to then start to see those as an indication of a factual phenomenon.

However, we have been working to do a bit better than this, which has become possible thanks to more resources, more experience, and more people providing information. Starting from early 2020, we have had a “quality” system in place, which takes a number of (essentially objective) criteria and puts them all together into a rating to reflect the “strength” of a given entry in our database. One of the things that usually makes the difference between an entry being “average” (Tier 2) and an entry being “strong” (Tier 1) is the presence of independent corroboration. In other words, a source other than friends/relatives abroad who are speaking for a given victim and who – in the age of social media – cannot really be seen as independent.

In most cases, independent corroboration means getting something from the Chinese side, which may be a court verdict, an arrest notice, or the victim’s presence in a leaked document. Radio Free Asia’s Uyghur service – and Shohret Hoshur specifically – have been instrumental in this also, thanks to their recorded phone calls to local government/police offices, in which they manage to get the local authorities to confirm that such-and-such a person has disappeared or was detained. In some cases, we obtain partial corroboration – about a person’s identity but not their detention – such as finding the online listing for a given victim’s mobile-phone shop (after their relative abroad testified for them and mentioned that they ran a mobile-phone shop). Sometimes, there are certain official databases or records that we may have partial access to and which we can search by the victim’s Chinese ID number, which then allows us to confirm a given person’s identity and/or situation. For a small number of (usually high-profile) victims, there may be official confirmation via Chinese diplomats or even Chinese state media, in which they confirm the arrest and detention but state that the person is a real criminal, which in some cases is obviously ludicrous. A particular case that comes to mind is that of Erkin Tursun, who was deemed a “Top 10” journalist for his region in 2017 and in the spring of 2018 was suddenly given 20 years for “terrorism” and “harboring criminals” (as stated by the Chinese authorities in both the state media and in an official communication to the UN).

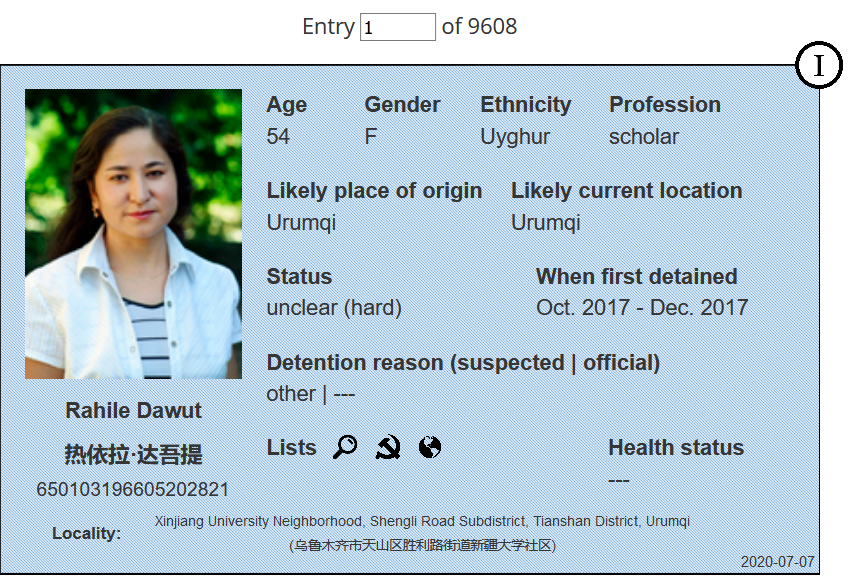

(Entry Number 1 in the Xinjiang Victim Database, the famed scholar Rahile Dawut. Disappeared December 2017 – https://www.shahit.biz/eng/viewentry.php?entryno=1)

Realistically, the number of victims which we can get independent corroboration for is quite small (probably no more than 5%), but taken together still makes for a very sizeable document. For people who are using our database and don’t know what’s trustworthy and what isn’t, we simply recommend to look at the rating in the corner of the victim’s card at the top of the page (if there is one, as not all have been rated). A “I” means that it’s a strong testimony and should be given a lot of weight, “II” means that it’s very likely reliable but lacking in detail/corroboration, while “III” you may avoid – unless you’re looking for simple things like age or gender. Of course, these are general guidelines and people are, again, encouraged to read and analyze themselves.

In terms of time and effort, I’m glad to say that this system is largely automatic and has generally worked very well so far, to the point where I don’t see any reason to tune it. So, if you design it well, it shouldn’t be too bad, although something that can take time for us is sourcing the information, as some entries are built from 10-15 sources and require some careful reading to dissect where the information came from. Of course, actually getting the independent corroboration is a different beast, and that’s either a lot of work (as it is for Radio Free Asia) or passive luck (as it is more for us). At the moment, we mostly operate passively, taking information as it becomes available, though we also do have a dedicated person whose job is purely to search the Chinese internet for the victims’ Chinese names, which sometimes yields very valuable results.

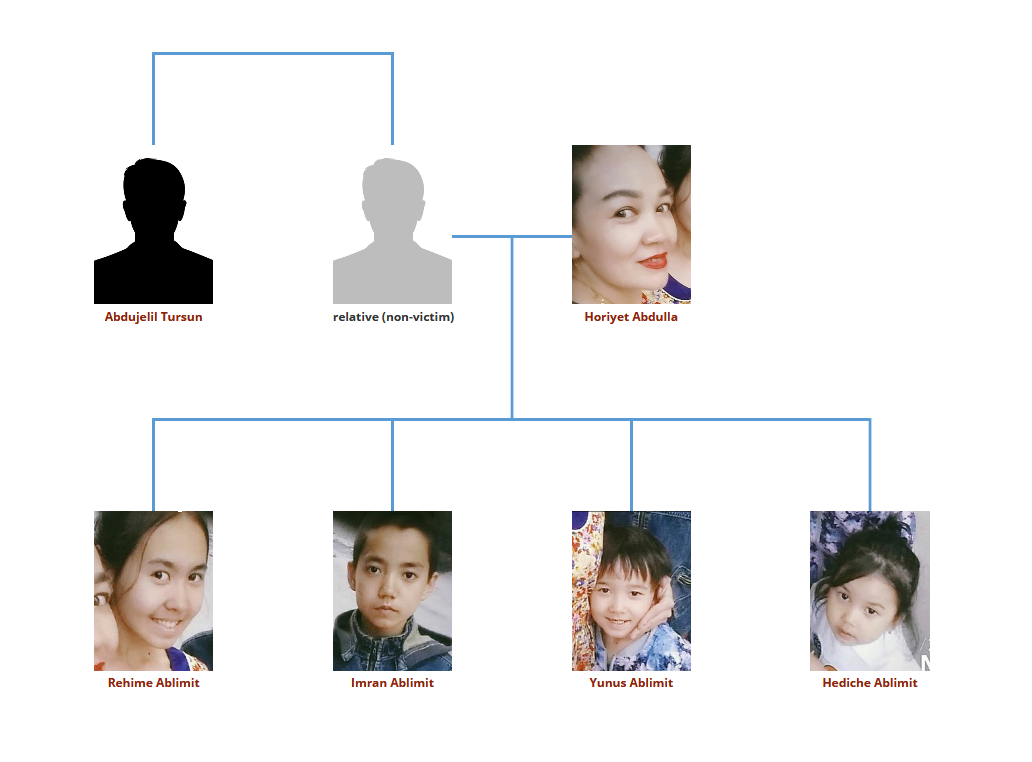

(The victims of China’s Genocide in Xinjiang often are entire families. Here Xinjiang Victim Database has diagrammed the tragedy of Abdujelil Tursun’s family: https://www.shahit.biz/eng/viewentry.php?entryno=5334)

AAT: Your projects are powerful, but in a way it makes me sad that you had to take these responsibilities on in lieu of governments or international bodies. Could you tell me what is it about why there is such deafening silence from global governments when it comes to Xinjiang? Why is it falling on journalists, citizens and organizers such as yourself to tell this story?

GB: Probably the key reason is the relative obscurity of the region, as it’s only in the past 1-2 years that more people have even learned what “Xinjiang” is, who lives there, and why life there isn’t always great. I think this is obvious when you compare it to Hong Kong, where the international reaction has been louder and much more swift. Personally, I think it’s too idealistic to expect governments and international bodies to just come in and “save the day” anywhere, really, and it falls on the regular people to force them to do so. China’s massive(ly cruel) social engineering campaigns affect very many, and this is the flip side to all of this – there is a lot of human capital that can be thrown at governments to do something about it because a lot of people care. Contrary to a lot of people, I’m actually pleasantly surprised by the amount of attention and action that this issue has received internationally, given the self-centered world we live in. I did not really expect this 2-3 years ago.

In general, I wouldn’t really advise anyone to rely on governments to solve these issues on their own. There needs to be a ton of grassroots and similar pressure.

Of course, this is where I can also say a lot of by-now cliché things about Chinese soft power and how it effectively buys silence on an issue that it itself probably knows is heinous. I won’t because it’s been said plenty, but naturally this is a big factor also, as it slows down the global awareness of the issue and makes it easier for many to ignore/deny it.

(Anthropologist and Writer Darren Byler reads the appeal letter of Bagdat Akin (shahit.biz/?f=bagdat-akin), a Kazakh student at the Al-Azhar University in Egypt, who was detained and sentenced to 14 years for “terrorism” upon returning to Xinjiang.)

AAT: Likewise there have been many reports on how corporations have profited from the forced labor of Uyghurs, Kazakhs, and other Turkic ethnic minority groups in the region. Do you have a sense from these testimonials about how either China-based or international corporations are profiting from the forced internment of Xinjiang’s peoples? If so are there ways that international consumers can boycott or otherwise oppose the actions of these corporations?

GB: Forced labor isn’t really something the testimonies have been incredibly useful for documenting – I mean, there are hundreds that talk about some sort of forced labor but the details are usually very weak, especially with regard to how they’re tied to international corporations, as this is not something most relatives testifying for people in Xinjiang would really know (or care to share, perhaps). A few eyewitness accounts talk about it, but most of these have been covered by mainstream media. It’s clear that it happens and that the scale is significant, if not massive, but we are probably not your best source for dissecting the actual chains. A point that I think is overlooked is the fact that prison labor is pretty standard all over China – Xinjiang included – and that most of the victims with prison terms are very likely contributing to that now. And this is hundreds of thousands of mostly innocent people, whose court verdict makes their labor no less forced than those being sent from camps to factories, say. There, it would be easier to dig in and investigate since the prisons are more official and established, and the companies that operate out of them are listed here and there.

International consumers can almost certainly protest and boycott, and should. Putting pressure on a company outside of China is significantly easier than putting pressure on China, and should be done. There has already been at least one successful case with Badger Sportswear, who agreed to pay 300000 dollars to organizations working on the Xinjiang issue following an investigation that showed how its stuff was originating from a camp-factory in Hotan. A project I was coordinating – helping ex-detainees in Kazakhstan get medical aid – got some of that money, which should help illustrate that the benefits can be quite concrete. So yes, certainly, please pressure these companies.

(A Food Vendor in Kashgar, pre-genocide. Photo Credit – Gene Bunin)

AAT: Lastly, what principles can we build both now and for future generations to stop the genocide of Xinjiang and ensure that something like this never happens again?

GB: I think the fact that we live in an information age where news of a local authority abusing their power can reach someone on the other side of the planet in a matter of minutes and elicit a reaction is definitely something, and while there’s much negative to be said about where phones and the internet are taking us as human society, it is also an incredibly powerful tool, and one that dictatorships fear greatly (and thus strive to suppress).

From this angle, documentation is incredibly valuable, because the authoritarian mechanisms that do these horrible things to people still do – at the end of the day – try to make it look like they play by the rules. This is a benefit of globalization. So, naming and shaming goes quite a long way, I think. Even if it can’t protect everyone, it greatly lowers the incentives for those who are doing these things to do them, as there will likely be a judgment day in the future – not in a dramatic sense, as some people are already preparing lawsuits. It seems obvious to me that more than a handful of people in Xinjiang’s security organs must have had such thoughts already.

In more pragmatic terms, if we want to stop people from starting genocides, the most effective way – apart from a balanced and humanitarian education, which takes many generations to sink in – is to make it risky and expensive. Whence the need for transparency and accountability.

(Gene Bunin – Founder of Xinjiang Victim Database, with Atajurt. Assisting Bikamal Kaken’s appeal for her husband, Adilgazy Muqai, recently confirmed as sentenced to 9 years.)

For more, please head to the Xinjiang Victim Database. Help support their cause with funding. Help share the voices of the voiceless. Help stop the genocide of Xinjiang: