Asia Art Tours was thrilled to interview comic book artist and author Joshua Luna. We had a wide-ranging interview on Race, Racism, Representation, Asian Identity and how his work explores these ideas.

Below you can find our conversation and links to Joshua’s work! I hope you enjoy our chat!

Asia Art Tours: Could you discuss your background to give us a brief snap-shot? Where did you grow up? And how did you get into the field of Comics?

Joshua Luna: I’m an American-born Filipino, but since my dad was in the Navy, I spent many of my formative years abroad—in Iceland, Sardinia, and Sicily (Italy)—before returning to Virginia permanently at age 15, when he retired and left us to start a new family.

I’ve been drawing and telling stories ever since I was old enough to hold a pencil, making homemade comics using stapled stacks of line art paper at an early age. I attended SCAD in Savannah, Georgia where I majored in Sequential Art, and after graduation I got my break in the comics industry with a blind submission of my first comic series, ULTRA, co-created with my brother Jonathan. Most blind submissions stay in the slush pile, so we were very lucky to get in that way. Soon after, CBS adapted ULTRA into a TV pilot, starring Lena Headey (as the protagonist) and Peter Dinklage, so that was another lucky break. For my first year or two as a professional, I thought navigating the industry was easy. But man, did I learn.

AAT: Were there other role-models who inspired you (or could help mentor you) as you entered the comic book industry? And what structural barriers have you personally had to deal with in the Comic Book industry?

You would think that breaking into the comic industry alongside my older brother would mean I’d have a natural source of mentorship and protection, but unfortunately, the opposite was true. A few weeks ago I came forward to talk about Jonathan’s emotional and physical abuse towards me that went on for over a decade while we worked together under the “Luna Brothers” name—to include cutting me out of profits and contracts, obfuscating credits, and trying to keep me trapped in a mortgage—but I haven’t talked about how hard it was (and is) to deal with the pressures of institutional racism while also dealing with being harmed by my own family, because honestly, it’s a lot, and there are many days where it’s hard to stay motivated to keep going.

How did you come up with AMERICANIZASIAN, and what struggles have you had with Image trying to publish the book?

After I parted ways with my brother, I wrote, drew, and published a solo comic book series, WHISPERS, and then started planning a new, unannounced series afterward. It was very ambitious and was going to take a long time to get ready for solicitation, but I wanted to somehow stay connected to readers in the interim.

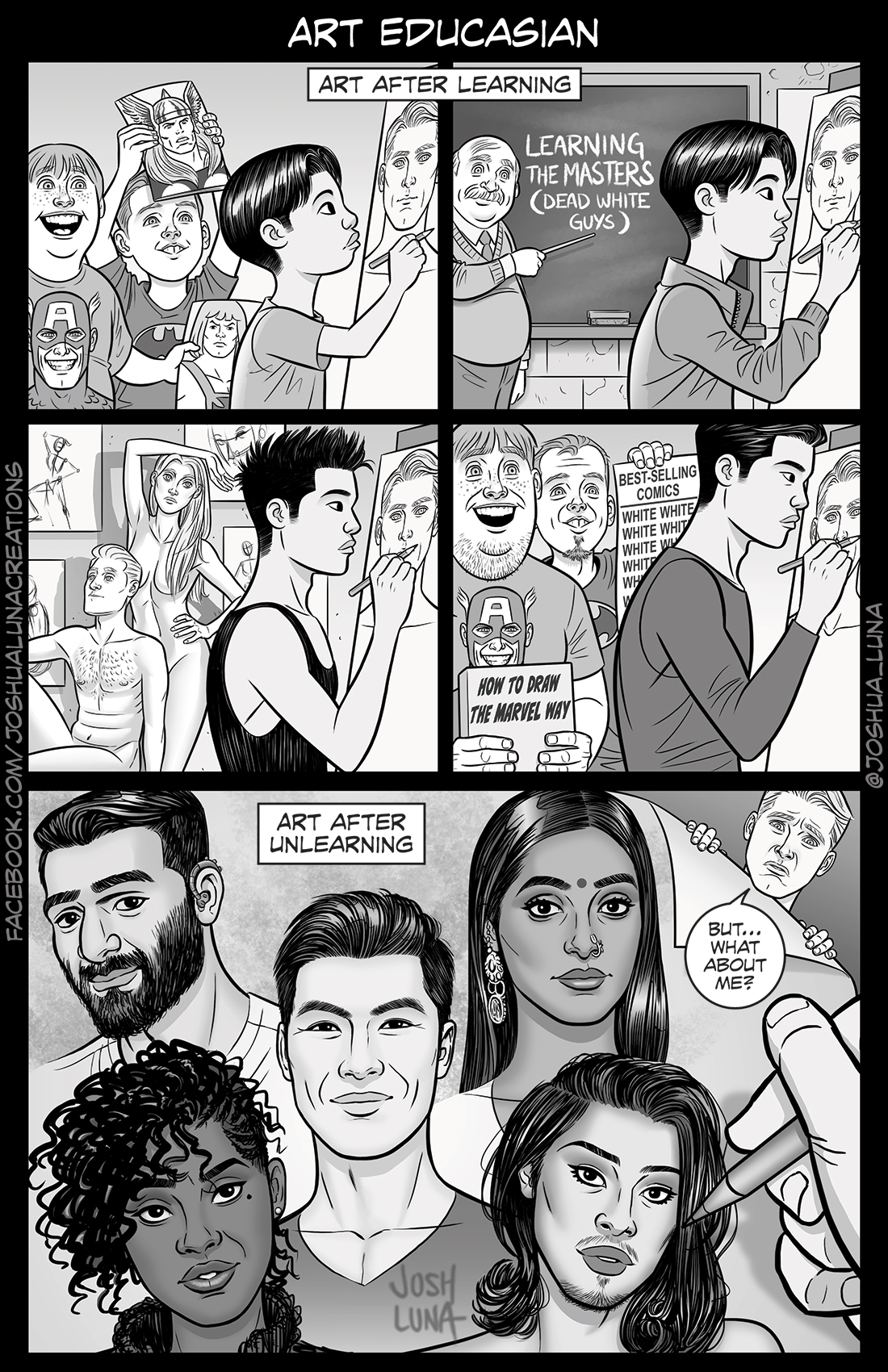

So, I started posting comic strips about my Asian/Filipino American identity and experiences every month. These strips were never meant to become a book at all, but they just took on a life of their own, organically growing into a communal therapeutic journey for me and others, as the comics resonated strongly with all kinds of people. When educators and other fans asked for a book collecting these strips so they could share them or teach them in classrooms, I realized I wanted to make this the priority project instead, so I decided to solicit it at Image as AMERICANIZASIAN: A Filipino American Comic Creator’s Awakening.

Unfortunately, despite having published with Image for 10+ years and having all of my previous projects enthusiastically greenlit with little editorial oversight or pushback, they not only rejected AMERICANIZASIAN, but did so in a way that made it clear that talking about race as honestly as I do was completely unwelcome at the company.

Why is the book so important to you that you’re willing engage with this struggle?

Although I’m proud of my previous works and am happy they resonated with so many people all around the world, I spent too many years of my career being erased, and wasn’t going to let it happen again. For the first time in my career, I wasn’t just pitching a story—I was pitching my own humanity. Fighting for this book’s right to exist and be published is an act of self-love.

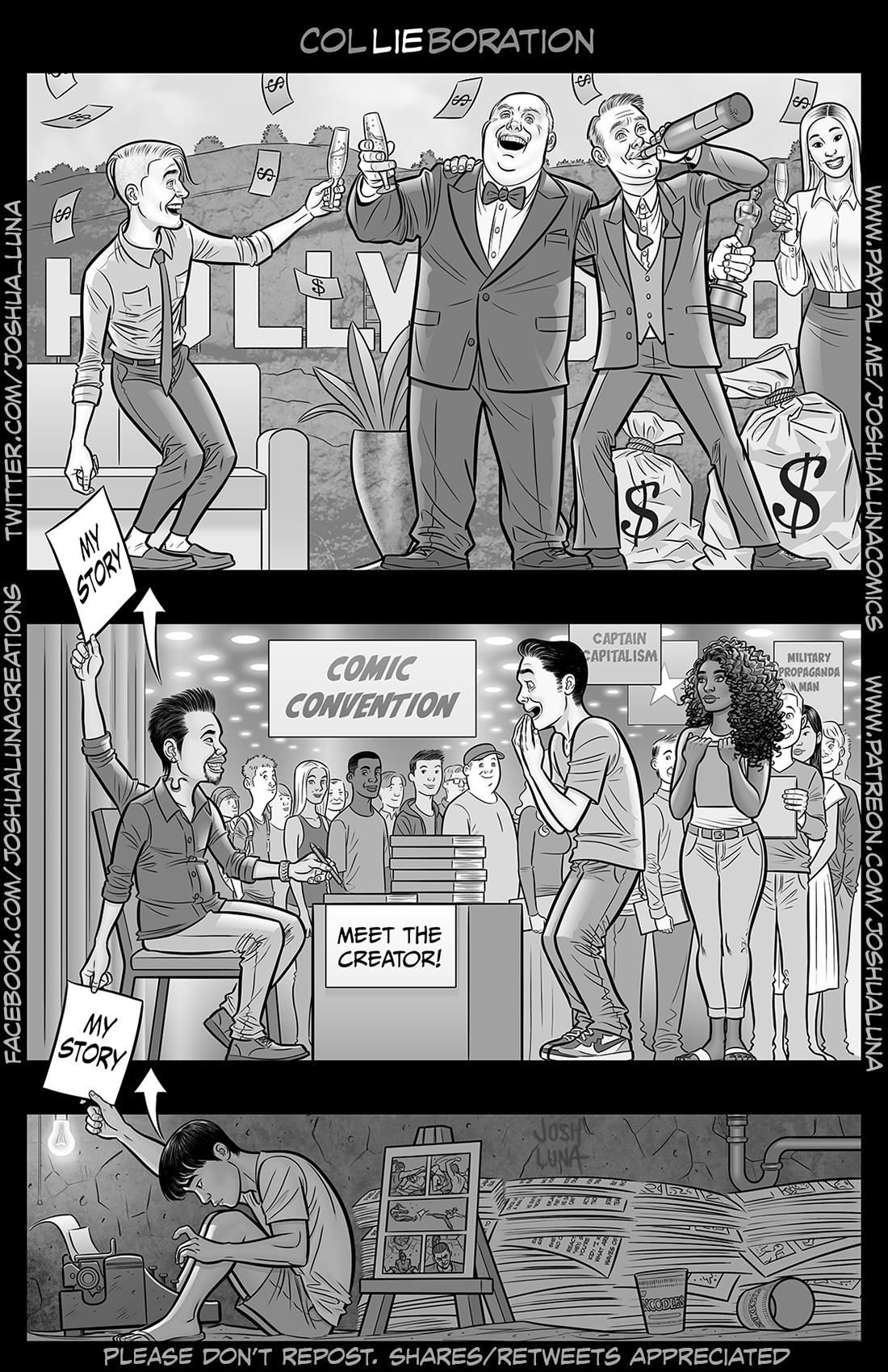

Specifically to Filipinx artists, how do major brands (DC and elsewhere) exploit the labor of Filipinx for their own ends in the Comic Book Industry? And how can they (and all exploited laborers in the industry) fight back?

The systemic erasure of Filipinx voices in comics means that the exploitation of Filipinx is a well-kept secret, which usually takes on two forms: 1) Filipinx are hired only as overworked, underpaid creatives (typically foreign, not domestic, and typically artists, not writers) who toil away on white-centered stories that erase us, or 2) in the rare instances where Filipinx stories are told, non-Filipinx (white or POC) are put at the forefront of telling them.

The only way to fight back is to publicly draw attention to these practices and speak up against them (which brings up the topic of unions or guilds in comics, but that’s a whole other conversation with its own complications), but there are consequences to this as a creator, as my experience shows—you will most likely be fired, replaced, or blacklisted.

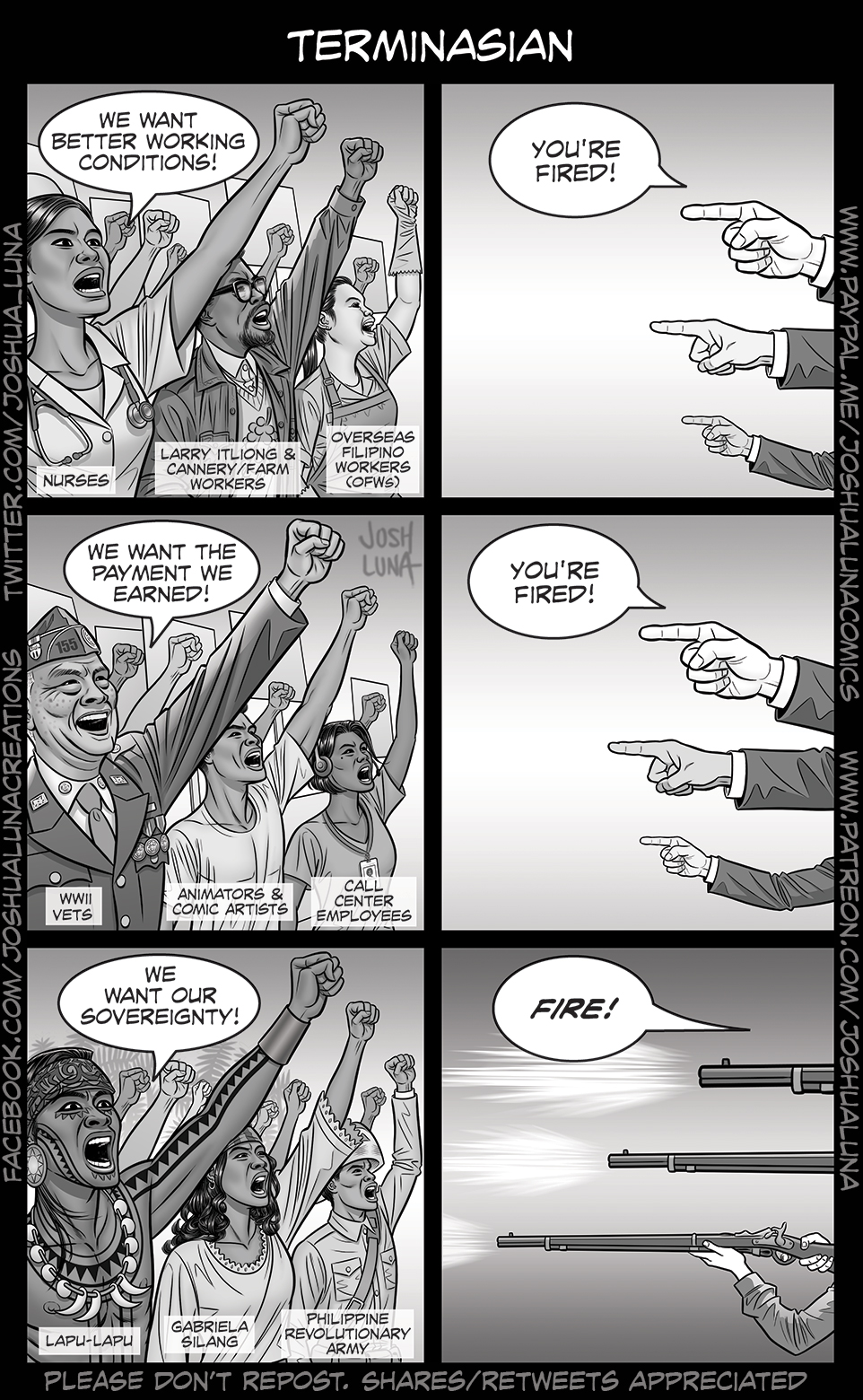

Using your strip TERMINASIAN as an example, could you discuss how this exploitation is just one link in a brutal Imperialist chain that stretches far back into history?

History has shown that Filipinx are viewed as either “little brown brothers” who need to be civilized out of our supposed savagery, or a yellow/brown peril that needs to be neutralized. Either way, we are not seen as human, and haven’t been for hundreds of years, thanks to colonization by both the Spanish and Americans. We’re constantly at the whim of an occupying oppressive force—even now—and our land and labor continue to be extracted and exploited because they’re seen as the ongoing spoils of war.

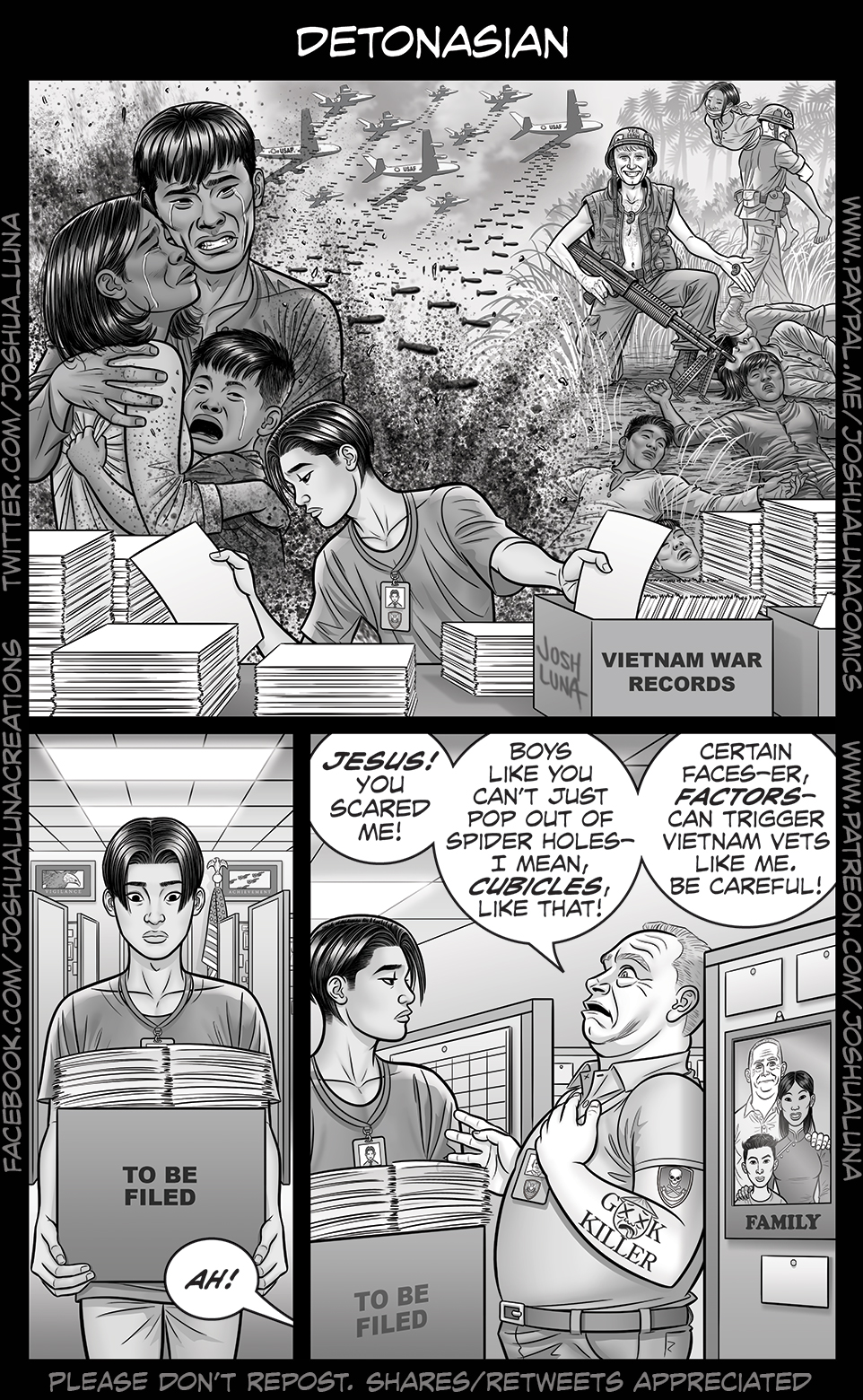

Regarding the strip DETONASIAN could you discuss how as a teenager, filing Vietnam war records made such a deep imprint on your personal beliefs and convictions?

This experience was one of the many reasons I felt the pressure to politically identify as American only for years, not Asian or Asian American. At that age, however, I couldn’t articulate any of these complex feelings—all I knew was that I was supposed to empathize with dead white American soldiers more than innocent Vietnamese civilians who had been murdered. I knew that if I had any empathy for “the enemy,” my allegiance would be in question, and I’d become the enemy too—even though I’m Filipino, not Vietnamese. So much of being Asian American is about being taught to internalize the white supremacist messaging that says Asianness is inherently villainous and deserving of violence.

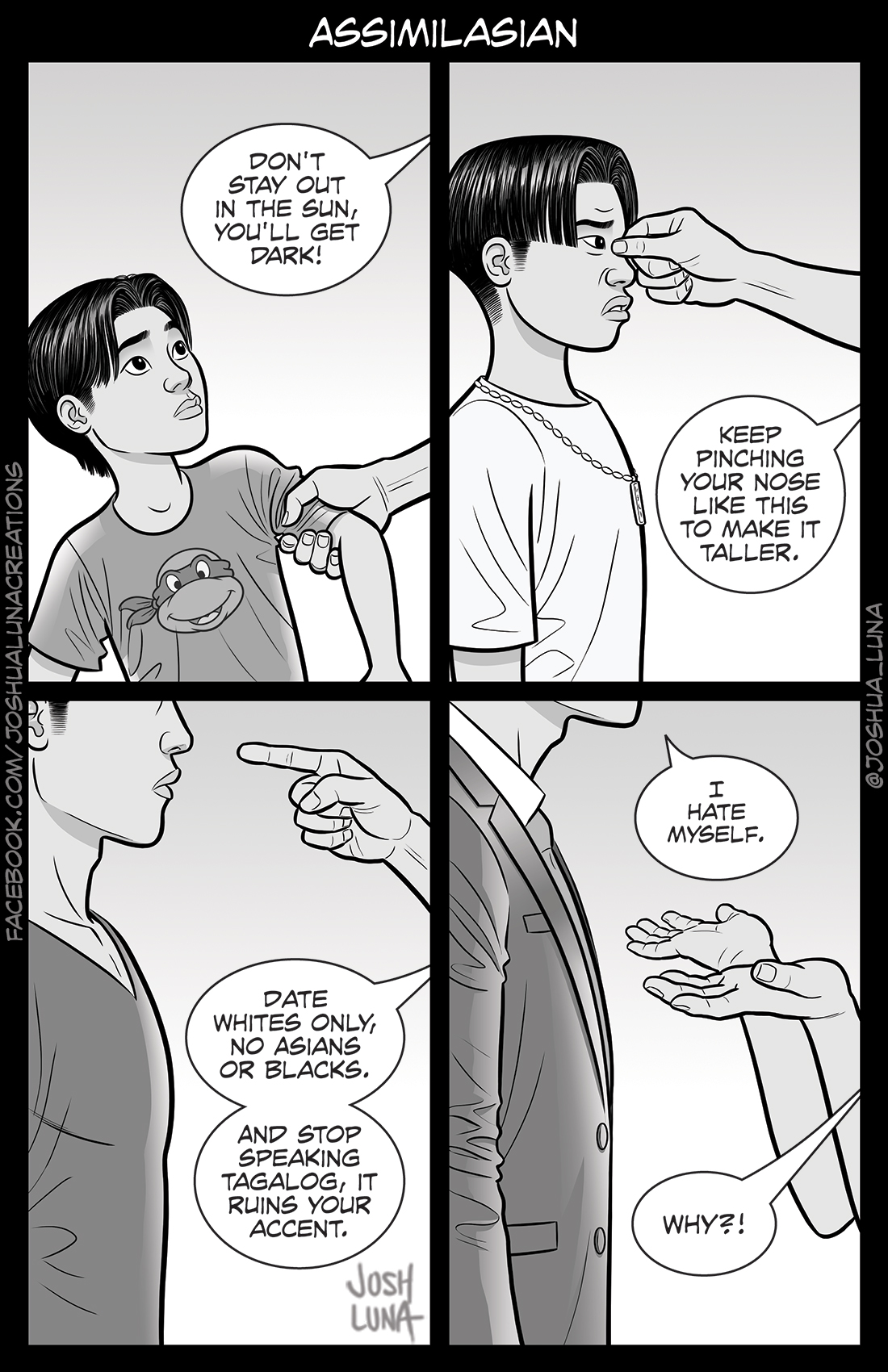

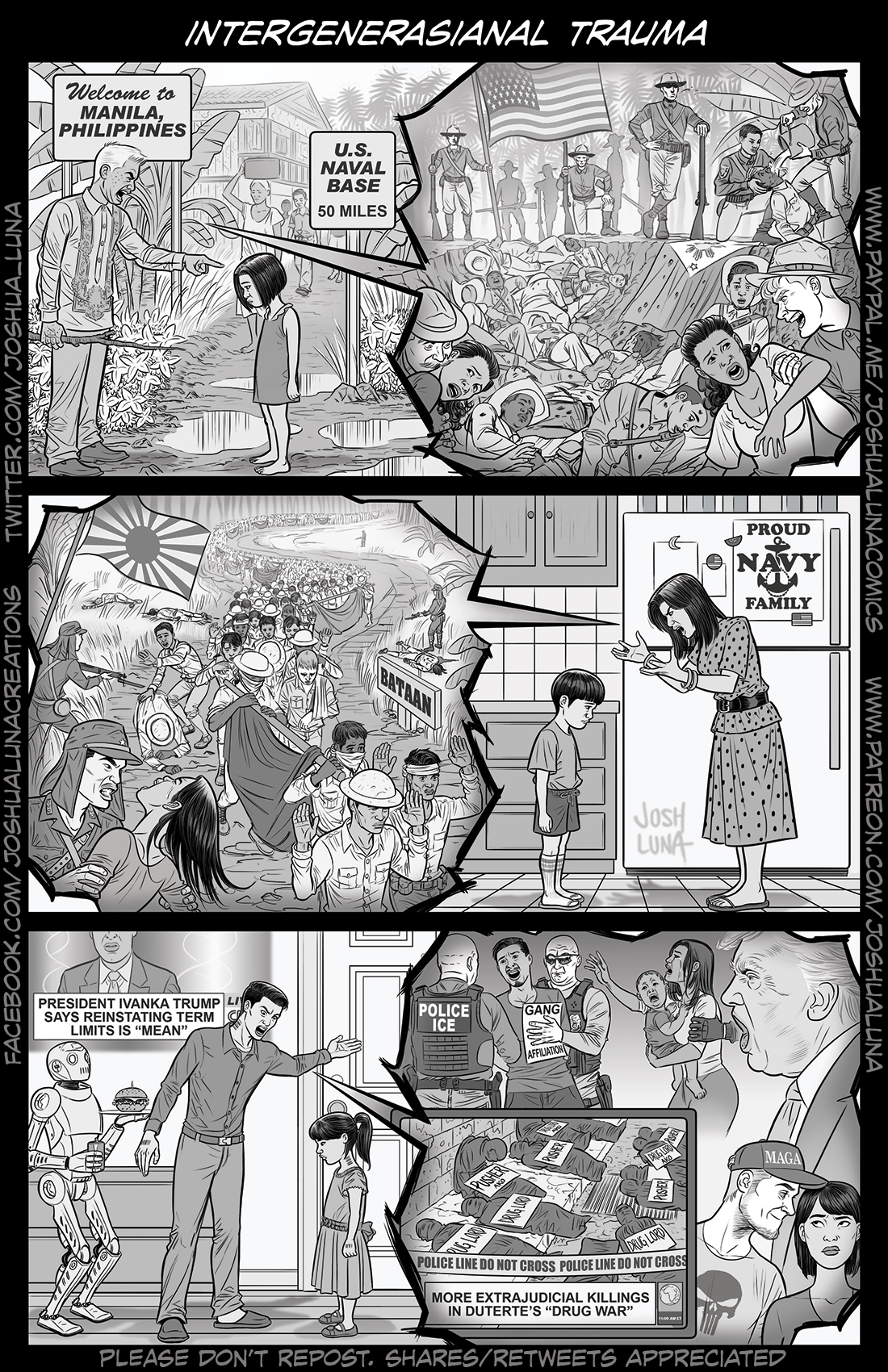

You have two strips titled INTERGENERASIANAL TRAUMA // ASSIMILASIAN Could you explain how trauma passes down and mutates from generation to generation (or specifically, for Filipinx)?

The myth of the American Dream has convinced many of us diasporic Asians that the trauma of colonization and war is something that stays in our ancestral lands, and that we’re automatically privileged over our immigrant parents just by being in the U.S. But the trauma follows our parents here, often because it goes untreated, and is then passed down through both epigenetic inheritance and learned behaviors—such as repressing emotions, poor communication and conflict resolution, verbal, emotional, and/or physical abuse, and ignoring or downplaying experiences of American racism in order to assimilate.

How do you intend to have your work help break this cycle of trauma?

Through making these comics, I’ve learned that healing from racism isn’t just an individual process but a communal one, and needs community dialogue—which means speaking honestly about our experiences with each other instead of pretending they aren’t happening. It is my hope that my work can bring healing to many by encouraging that dialogue, however difficult it might be to do so.

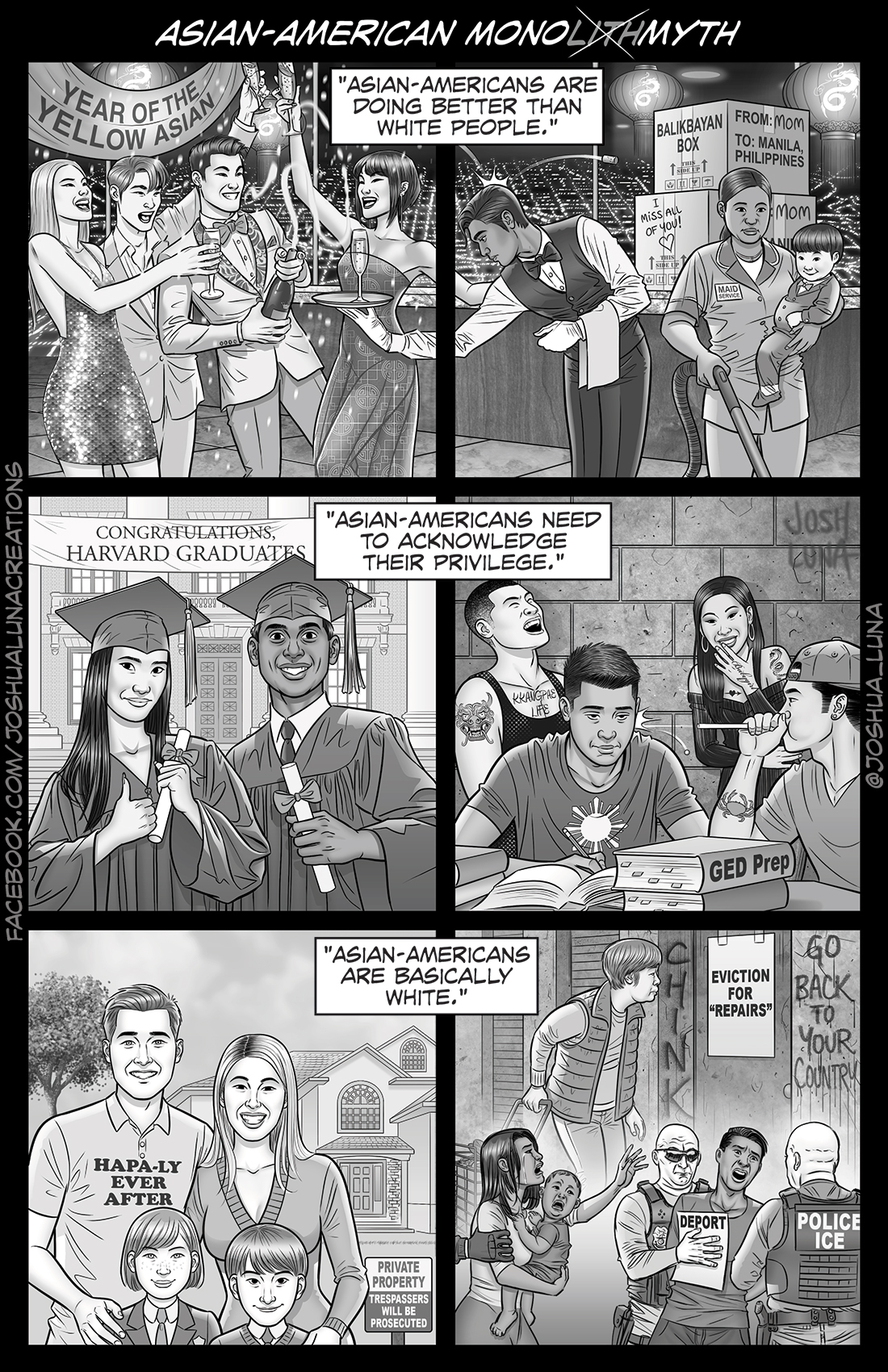

My favorite strip of yours is the ASIAN-AMERICAN MONOLITHMYTH. Could you discuss what is the myth of the Asian Model Minority? How do we see it perpetuated through American Culture? Why is it so harmful? And what can we do to shatter the myth entirely?

The Model Minority myth is a falsehood created by white supremacy that projects non-racial privileges like class, education, etc. onto Asianness to imply that Asians are inherently privileged due to our race, and therefore don’t suffer from white supremacy. It is used as a wedge not only against other communities of color, but as a wedge within our own community, erasing the most marginalized amongst us—which includes poor or less educated Asians, undocumented Asians, dark-skinned Asians, and Southeast Asians.

The reason why the myth and other forms of anti-Asian racism are so hard to dismantle is because white supremacy rewards Asian Americans who internalize this messaging with power so they can help keep the system intact, and these complicit Asians get defensive or even aggressive when it’s pointed out. For instance, when I talked about a particular form of internalized racism in my comic RECONCILIASIAN, I was harassed by a group of Asian Americans on Twitter who knowingly spread false rumors about me in POC spaces for over a year to try to de-platform me and destroy my livelihood—just because of that one comic. I remember you recently asked a prominent East Asian figure on Twitter why they weren’t promoting or supporting me (when they had in the past), and this is why—because they are personal friends with several of the people who either participated in the harassment or encouraged it, and have been recruited into helping my harassers prevent me from being featured by any major Asian American platform, particularly East Asian-controlled. They are furious that I didn’t toe their party line of pretending this form of internalized racism doesn’t cause real harm, and that I defended myself from their harassment. I was supposed to pledge fealty to them or go away, but since I’ve done neither, they’re pulling the levers of power they have in Asian spaces to shut me out.

So although uprooting the Model Minority myth is a worthy goal, we have a long, long way to go in learning to fight the system and not each other.

You had mentioned how MULAN had a great impact on you. I’m wondering if you could talk about this movie, what was its personal impact?

Growing up, I rarely saw Asian faces on screen, either live or drawn—especially ones that made me feel proud to be Asian—so when I saw MULAN as a 17-year-old aspiring comic book writer and artist, I felt both seen and inspired. MULAN encouraged me to draw Asian faces and write Asian narratives in my homemade comic books all throughout high school. This preference for Asian protagonists was unfortunately trained out of me in art school at SCAD (a training which then took years to undo), but the impression MULAN left never fully left me.

How can we both be furious at Disney (or any company’s) capitalist practices, while still finding hope or strength in their products?

It is very Stockholm Syndrome-esque, but unfortunately, I think that is the plight of diasporic Asians and other people of color. For better or worse, this is our home, and these corporate monopolies have a material effect on our lives and how we are seen and treated whether we like it or not. So personally, I think it’s important to be invested in those depictions and fight for authentic, positive representation as best we can, even while working simultaneously to fight capitalism and dismantle creative monopolies.

To conclude with a speculative question… what cultural forms do you think exist, if we’re able to continue pushing back on capitalism, racism, sexism and imperialism… what notions of utopia do you think exist beyond that horizon, that AMERICANIZASIAN is perhaps one small step towards?

Even though most of the feedback for my comics is positive, I’m getting a lot of quiet but powerful and damaging institutional pushback from both white-dominated comic spaces and East Asian-dominated activist spaces who see me speaking truth to power in my content as an existential threat to their status quo. So ideally, I want to see a world where creators of color like me have a safe space to speak truthfully about our experiences—whether that’s in comics or elsewhere—and I want to be one of the people who not only get to enjoy that space, but also help build it, so that others have an easier time than me.

If you’d like to support or learn more about Joshua, you can donate or check out the following links!

Patreon: https://www.patreon.com/joshualuna

Paypal: https://www.paypal.me/JoshuaLunaComics

For Joshua’s Social Media Presence, please head here!

Joshua’s Twitter: https://twitter.com/Joshua_Luna

Joshua’s Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/joshualunacreations

Joshua’s Tumblr: https://joshualunacreations.tumblr.com

Joshua’s Website: www.joshualuna.com