To better understand how Racial Capitalism, Patriarchy and Blackness flows between Africa & the United States we were honored to speak with Dr. Jordanna Matlon. Her articles in Boston Review and her research in Côte d’Ivoire remain essential for understanding how to end the violent injustice of the world as it is.

Dr. Matlon was kind enough to join me in conversation on her work. All photos provided are from Dr. Matlon’s Fieldwork in Abidjan, Côte d’Ivoire

Asia Art Tours: Your article Racial Capitalism and the Crisis of Black Masculinity, studied global (late) capitalism and masculinity through fieldwork and interviews with men from Abidjan, Côte d’Ivoire’s informal sector in 2008.

I’d like to put this in dialogue with Acclaimed Scholar Achille Mbembe who said of the neoliberalism of this period: If a neo-liberal way out of the crisis has – so far – led to any renewal of growth, it is growth with unemployment … it is quite reasonable to hypothesize an end to a wage-employed African labor force.

Dr. Jordanna Matlon: I should begin by contextualizing my field site. What is known as the “crisis” in Abidjan as elsewhere in Africa began with structural adjustment in the 1980s. These austerity measures imposed by the Bretton Woods institutions effectively gutted inchoate state-funded social welfare systems. This is the starting point for much of the contemporary scholarship around urban informal economies and “youth” cultures. I say “youth” because it is a social, not a biological category, and refers also to men who lack the financial stability to be considered marriageable and hence to become social elders in their families and communities. The concept is of particular significance to my research examining masculinity and the unattainable breadwinning ideal, because underemployed men in Abidjan lacked work that would properly designate them as “men,” and instead they remained “youth.”

(Images of America, as seen by Abidjan. Photo Credit: Jordanna Matlon)

(Images of America, as seen by Abidjan. Photo Credit: Jordanna Matlon)

The crisis is another way of referring to neoliberalism, which is certainly the contemporary regime of racial capitalism. While former modalities of racial capitalism have incorporated Black people as undervalued, hyper-exploited laborers, in my article I argue that neoliberal domination manifests as exclusion: they are shut out of the formal workforce altogether. When I set out to study excluded men, however, I still needed to find men engaged in some form of economic activity. This is about context: the informal economy is what exists when there is neither “employment” nor a formal safety net. Rather than fall into a category of “unemployed,” you find people fending for themselves; otherwise they will die. The informal economy represented around 75% of work in Abidjan, which is frightening when you have a real sense of the extreme precariousness that entails. Survival in this economy depended on robust social networks, and how best one was able to position themselves within those networks.

Achille Mbembe’s observation from 2001 about growth with unemployment accurately predicted the African “renewal” in the new century – what many pundits have celebrated as Africa Rising. That narrative lauds both an emergent class of fabulously wealthy Afropolitans and a petty consumer class, the latter which has been dubiously termed the “fortune at the bottom of the pyramid” – but against the ignored backdrop of entrenched informality and all the insecurities this kind of work entails.

(A Vendor holding a Shoe. Photo Credit: Jordanna Matlon)

(A Vendor holding a Shoe. Photo Credit: Jordanna Matlon)

I should nevertheless note that there was not much of a formal economy before the crisis: this point is often missed in these conversations, and as such a narrow focus on neoliberalism obscures the more deeply entrenched political economy of racial capitalism. The division between formal and informal work began with colonialism. Wage-earning jobs within the colonial realm, predominantly in the civil service or with private companies that typically involved extraction of African resources abroad, were for a privileged few. Activities, productive or reproductive, that came before colonialism and which had not been captured by the colonial economy were denigrated as non-modern, regardless of how essential or prevalent they were; market activities are a prime example of this.

I must add the descriptor feminine as well – women were shut out from the new wage economy, and women’s activities were lumped into the non-modern category. Upon independence, all these non-modern activities fell under the definition of an informal economy. These are the jobs that remain when global capital retreats from employing African labor. What has changed, then, is less the demise of a robust formal economy than the expectation, or hope, that a wage labor economy to facilitate breadwinning – the kind of work envisioned in a gendered, developmental narrative of progress – would appear.

Thus the precarity of the African labor force is indicative not just of neoliberalism but of the colonial influence on African economies: first by producing this bifurcated world of wages or not; and second, by creating a normative framework that stigmatizes the majority of men shut out from “good jobs” and hence breadwinning masculinity. In the book I am currently finishing up, A Man among Other Men: The Long Crisis of Black Masculinity in Racial Capitalism, I step away from talking about neoliberalism at all to emphasize racial capitalism in the longue durée.

(Photo Credit: Jordanna Matlon)

(Photo Credit: Jordanna Matlon)

Asia Art Tours: From your studies in Côte d’Ivoire , could you explain who the vendors are and within the neoliberalism that they preached, why did they see their own personal class salvation, within economic systems that would lead to the destruction of Côte d’Ivoire’s (and Africa’s) labor force?

– Then could you describe the Vendors? Why did they continue to revere a capitalism that forced them into a life of the ‘precariat’ unable to perform the gendered function of the ‘breadwinner’, rather than embrace revolution against the patriarchal capitalism that demanded they be breadwinners in the first place?

Jordanna Matlon: I studied two groups of men in Abidjan, whom I selected based on their remunerative activities: orators and mobile street vendors. These groups were significant because they were very public symbols of crisis in Côte d’Ivoire – orators of the political crisis, and vendors of the economic crisis. Orators were political propagandists for then-President Laurent Gbagbo and gave speeches at a venue in Abidjan’s well-heeled center nicknamed the “Sorbonne.” They did not make much doing this, but it was enough to survive, and crucially, their service to the Gbagbo regime entrenched them within its patronage network. In the long-term, they hoped this network would help them, as they described it, “finance future entrepreneurial projects.”

Mobile street vendors sold anything they could in the middle of traffic and were truly at the bottom of Abidjan’s social and economic hierarchy. They experienced the state as a predatory institution, as police targeted for their “illegal” vending, seized their goods, and occasionally jailed them. So while both groups contended with the stigma of informality, the former’s relationship to the state was critical to helping them survive and even garner some status. Vendors on the other hand acknowledged that there was no dignity in their work, and looked to activities like music and sports that had propelled Black men to fame throughout the world while also carving out status among their peer groups through sartorial performances and petty consumerism.

(A vendor wearing international Icon and Commodity, Michael Jordan. Photo Credit: Jordanna Matlon)

(A vendor wearing international Icon and Commodity, Michael Jordan. Photo Credit: Jordanna Matlon)

Observing that orators and vendors espoused identities as future entrepreneurs and anticipatory consumers, I connected this to the strategies Black men elsewhere use to express agency outside of the breadwinner model, particularly in the United States, a country that Abidjanais men seized on as an idealized hegemon in contrast to the Franco-Ivoirian neocolonial relationship. And just like the diminished possibilities in Abidjan that produced these alternative imaginaries, identities formed by brands and dreaming of becoming the next LeBron James or Jay-Z in the United States must be situated in the reality that schools in Black neighborhoods are pipelines to prison as much as to well-paying, 9-to-5 jobs – and in that sense, a model of success predicated on one is no more improbable than the other.

Moreover, one garners far more attention in the public imaginary of Black male potentiality. I argue that this is a function of Black masculinity in the long crisis of racial capitalism for two key reasons. First, celebrity entrepreneurship has an established history of earning financial rewards and renown for Black men when traditional breadwinning avenues have been closed. Second, the slave economy initiated a relationship between commodification and the Black body, either as a commodity itself or by denied access to commodities: the right to dress a certain way, the ability to afford certain consumer goods. So these entrepreneurial and consumer identities, while celebrated in the flexible, neoliberal, every-man-to-himself economy, have an enduring legacy for Black men’s differential incorporation in racial capitalism. Within neoliberalism we see Black men – in the United States, across Africa – idealize these identities and depict them as solutions to their precarity. But these have only ever been successful strategies for the few, and were in fact historically a product of Black men’s structural exclusion, with resonances that extend into the present.

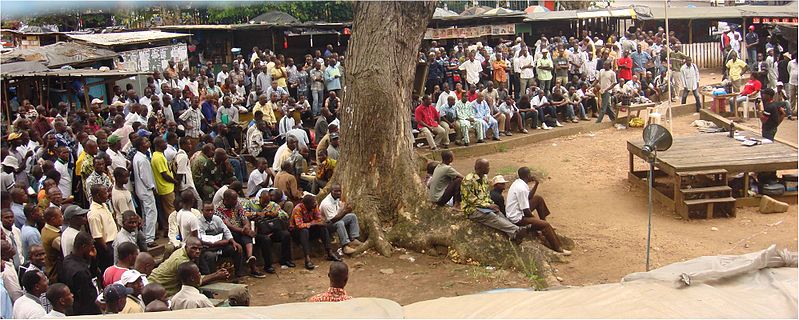

(Orators gathering to discuss politics. Photo Credit: Wikicommons)

(Orators gathering to discuss politics. Photo Credit: Wikicommons)

Asia Art Tours: You then explore masculinity via the frameworks of Raewyn Connell’s Hegemonic vs. Complicit Masculinity. You write: ‘Complicit masculinity affirms that masculine agency is located within capitalism so that, to borrow from Margaret Thatcher, there is no alternative to being a real man that is not rooted foremost in this relationship to capitalism despite one’s own marginal position.’

For much of modern history, women were forced to seek partners based on ‘bread-winning’ due to their exclusion from capitalism. However we now have a world with more women in the labor force than ever and where the economist Branko Milanovic has discussed the stark co-rise of income inequality and ‘assortative’ coupling based on elite class backgrounds as the main ‘romantic’ consideration .

For the subjects of your study (‘orators and vendors’), how might their complicit masculinity differ from a Princeton econ grad who marries her Goldman Sachs-bound beau? As we move higher in the income bracket between both partners, do we also move from ‘complicit ‘masculinity’ to ‘complicit social reproduction’ where both partners are fully aware of the class implications of their romance?

(A vendor selling commodities, with the commodified image of women behind him. Photo Credit: Jordanna Matlon)

(A vendor selling commodities, with the commodified image of women behind him. Photo Credit: Jordanna Matlon)

Both men and women define the criteria for what constitutes a “real man.” The social context in Abidjan and across much of urban Africa combined the European capitalist notion of man-as-breadwinner with a precolonial African notion of man-as-husband and father. Since colonialism, access to the wage economy has therefore mediated access to marriageability and “legitimate” fatherhood, without which men were not “real men.” This was and is as much a self-imposed norm among men as a serious factor that makes men without good jobs undesirable to women.

Men without formal work would likely be more attractive partners if Europeans had not so effectively entrenched the ideal of a gendered wage economy in their colonies. Breadwinning was a colonial invention in Africa. Prior to this, African men and women both contributed “productive” labor to the family unit. The colonial economy explicitly excluded women from new, wage-earning jobs, and stigmatized working African women as backwards and as a sign that African men were lazy. A painful irony is that Euro-America has reached substantial ideological parity at least – gender income inequality is still very real – while many formerly colonized societies are stubbornly committed to gendered norms around production and reproduction.

I should also emphasize that the orators and vendors, barely getting by in Abidjan’s informal economy, lived in a very different world from the Princeton econ grad and Goldman Sachs couple you describe above. For people seeking partners at this bottom rung of the economy, it is not a matter of status so much as survival. It would be a bit harsh to depict survivalist imperatives as “complicit social reproduction.”

(Photo Credit: Jordanna Matlon)

(Photo Credit: Jordanna Matlon)

But the point to underscore here is that the global political economic order under racial capitalism led to calculations that accord value to partners based on their financial worth, while leaving Black men consistently unable to meet those expectations. The experiences of men in African urban informal economies illuminate a predicament shared by Black men around the world.

Asia Art Tours: One of my favorite quotes comes from the Japanese writer Osamu Dazai – “Man was born for love and revolution”. In the context of your article’s framing and the tasks it inspires, what does masculinity look like if we can move beyond the hegemony of patriarchy? Is it possible to move beyond this hegemony under capitalism? In other words, what does love look like after revolution?

Jordanna Matlon: The hegemony of patriarchy in capitalism sets marginalized men up to fail, and it achieves this precisely because gender norms establish incredibly powerful boundaries around social conceptions of total personhood. The stakes of masculinity are then very high, while the built-in inequality of capitalism ensures that these masculine ideals cannot be achieved by all men. The task is then to destabilize the heteronormative terms of value and their attachments to what constitutes productive and reproductive labor. What possibilities for inclusion might there be, for example, if “responsible” fatherhood involved the provision of care rather than narrowly encompassing the provision of material resources? Yet when meeting basic needs is not assured, it is difficult to disaggregate materiality from care at all. The conditions to do so would indeed be revolutionary.

(Photo Credit: Jordanna Matlon)

(Photo Credit: Jordanna Matlon)

For more w. Dr. Matlon, please check out her research and main website here: https://jordannamatlon.com/