I spoke to Karen Cheung, essayist and author of The Impossible City: A Hong Kong Memoir, on Mental Health & Post- NSL Life in Hong Kong.

You can find our conversation below!

Asia Art Tours: Our conversation will be centered around Mental Health & Hong Kong. In researching your memoir, I came across the following statistic:

Although fees are very low, the normal wait to get an appointment (for Hong Kong’s mental health system) is more than two years. Over 300,000 people are in Hong Kong’s public mental health system with only 400 psychiatrists in the territory.

During the Hong Kong Protests, was mental health care something available to protesters? Or did mental health care become another site of ‘mutual aid’ in Hong Kong?

Karen Cheung: There certainly wasn’t an official campaign to promote mental wellbeing on the part of the government during the protests, but mental healthcare was still available, generally speaking. Residents could queue at the public hospital and hope for an appointment with a psychiatrist, but it might only come in the next couple of weeks, even years, given how overloaded the system is.

There were a lot of mutual aid initiatives—social media accounts that offered to listen to protesters who wanted to rant, or grassroots initiatives that arranged social workers to those who needed help; I interviewed some of them for The Impossible City. There’s pros and cons with this; in mutual aid, if the people offering help aren’t professionals, the situation could get out of hand (for instance, an untrained professional may not know what to do when someone talks about harming themselves at three in the morning). Obviously, they also can’t prescribe medication, which more severe cases—psychosis triggered by PTSD, for instance—would require.

Still, thank god those services existed; there was such a huge surge of Hong Kong residents in need of mental health care that there was no way the existing system of psychiatrists, social workers, and therapists would be able to handle them all. They at least filled the gap for those who might not need immediate medical attention, but just wanted to feel a little less alone—and hopefully that would be enough, at least for the time being, to prevent them from developing more full-fledged conditions.

There was such a huge surge of Hong Kong residents in need of mental health care that there was no way the existing system of psychiatrists, social workers, and therapists would be able to handle them all.

The Banyan Tree of Blake Park. Residents of David Trench Rehabilitation Centre could gaze at the park to find peace amidst Hong Kong’s overcrowded mental health facilities. PHOTO CREDIT: Wikipedia

The Banyan Tree of Blake Park. Residents of David Trench Rehabilitation Centre could gaze at the park to find peace amidst Hong Kong’s overcrowded mental health facilities. PHOTO CREDIT: Wikipedia

Asia Art Tours: With Hong Kong’s newly enforced Natural Security Law (NSL) how has mental health care been impacted? Can I talk to my therapist about the reasons I may want to commit suicide (my friend is in jail!) ? Can I honestly discuss why i’m so fucking angry (I live in a police state!) ?

What does mental health look like in Hong Kong where it may feel terrifying to express what one really thinks?

Karen Cheung: A huge problem with the mental health situation now, which I also highlighted in the book, is that trust within society is fundamentally broken. People are careful, even with friends, colleagues, and family members, with regards to who they confide to, and this means we’d be less open and honest with even mental health professionals. On forums, there are threads where people would ask for recommendations for specifically “yellow” (pro-protest) psychiatrists, and the pool itself is already so limited in the first place.

Then there’s the class divide—mental healthcare is expensive, and if you can only afford to go to a government psychiatrist, you’d likely not mention the real reasons behind why you’re experiencing depression or self-harm.

I’m always worried about badmouthing the public mental health system too much, because I’m concerned it’ll deter people from seeking help, but the truth is I stopped going because I had been sexually harassed by a fellow patient in the public outpatient clinic. The staff not only did not do anything to help, but were very condescending when I asked where they were. It’s always been plagued with an array of problems even before NSL.

Last year, I signed up for online counselling services, which provided me with an American therapist. It wasn’t cheap, but at least I could talk about protests and my anxieties relating to the political situation without the fear of someone reporting me. The downside is that it’s so hard to explain what’s happening in Hong Kong to an outsider that it took up a lot of the hour or half-hour allocated for the session—eventually I gave up and sought for help with a therapist here that I’ve now grown to trust.

Trust within society is fundamentally broken. . . On forums, there are threads where people would ask for recommendations for specifically “yellow” (pro-protest) psychiatrists, and the pool itself is already so limited in the first place.

Hong Kong Police, beating young people during the 2020 democracy protests. PHOTO CREDIT: Wikipedia

Hong Kong Police, beating young people during the 2020 democracy protests. PHOTO CREDIT: Wikipedia

Asia Art Tours: On Hong Kong’s Sai Wan 西環 Western District you write:

On weekday mornings at the cargo dock, ships unload their freight and trucks drive in to tow the goods away, but from late afternoon the technically-off bounds pier transformed into a utopian space where all the suffocating rules governing publicness in Hong Kong no longer applied.

It is one of the few waterfronts in the city not bounded by railings, no security guards to pull back anyone who just wanted to see the sea. Residents rode their bikes, smoked weed next to ship containers graffitied with obscenities, and cast their fishing rods into the water. We let our dogs off the leash.

Having written about many of Hong Kong’s neighborhoods, what about Sai Wan allowed it to both break rules and remain ‘illegible to authorities?

Karen Cheung: Sai Wan is a strange place. Apart from all the markers of British colonial legacy that I mentioned in the book—from the name of some neighborhoods within Sai Wan itself to even the word praya, meaning the waterfront—the district is also, for Hong Kong people, synonymous with the China Liaison Office, the political representative of the Communist Party in Hong Kong. That’s because the headquarters for these mainland officials in charge of the city’s affairs are in Sai Wan itself—and so sometimes Hong Kong people would say ‘西環治港’, which can be literally translated as Western District/Sai Wan governing Hong Kong, to mean that the Hong Kong government is carrying out the orders of the central government in China (rather than being so-called ‘autonomous’). It’s a district that is by default loaded with political meaning to begin with, and so most of the major protests in that area, during and pre-2019, has been in around the vicinity of that building.

The cargo pier, which is about ten minutes away from the office, has always symbolised, at least for me, some sort of utopic space that isn’t really supposed to exist in Hong Kong. Most public spaces in the city are governed by these bureaucratic rules of what is or isn’t allowed in parks; the cargo pier wasn’t even intended for public access in the first place, it’s for cargo workers to unload freight during the day.

And yet, residents of the area found their way in, and it was a space by the water where they could let loose after a long day at work, take a stroll with their dogs, hang out till the sun comes up. You have to get in through this small, side entrance where a sign tells you it’s for the Marine Department, and not the general public, but that didn’t stop people from turning it into an anarchist playground of sorts. There weren’t really security guards or cops roaming around telling you what you weren’t allowed to do, as is the case with most public spaces—of which we’re in dire need in the first place, given the size of our apartments.

And eventually, like most good things, it was closed off to the public. Part of the reason why it was closed, at least according to some reports, is that as popularity of the pier grew, the users of the pier also became undisciplined and were disrespectful of the structures belonging to the cargo workers. I think it’s a shame that it closed, and in a healthy society these issues should have been left for residents to discuss and work out on their own rather than outright banning access, it could have been a good lesson in what it means for people in a place to negotiate and learn to accommodate others who share that space with them. Only, of course, like the rest of Hong Kong, it just became another case study of, ‘OK, you misbehaved, so now you don’t deserve to have this place anymore, we’re taking it away from you.’

There weren’t really security guards or cops roaming around telling you what you weren’t allowed to do, as is the case with most public spaces—of which we’re in dire need in the first place, given the size of our apartments. Eventually, like most good things, it was closed off to the public.

Locals enjoying the San Wai Port. PHOTO CREDIT: Wikipedia

Locals enjoying the San Wai Port. PHOTO CREDIT: Wikipedia

Asia Art Tours: Has Sai Wan gone from illegible to legible or ‘semi-legible’ via surveillance & state violence? (Large dogs are leashed but small dogs still roam free, the weed is now clove cigarettes?)

Karen Cheung:It’s really hard to say right now what ‘mischief’ there can be left at all, after both the national security law and the social distancing guidelines imposed in the midst of the pandemic. These daily, small acts of exertions of freedom—they’re completely impossible when currently, even gatherings of more than two people in a public space are banned.

Another type of these spaces operating largely outside of the confines of the state, which is also in the book, is the warehouses for underground music shows; they’re still around, but obviously the pandemic made it difficult to do any gigs. I think we’ll get a better sense, after the pandemic (if it ever ends) of what’s left, what spaces still has potential for this type of not-explicitly-political resistance.

I think we’ll get a better sense, after the pandemic (if it ever ends) of what’s left, what spaces still has potential for this type of not-explicitly-political resistance.

The XXX underground Music Venue. PHOTO CREDIT: Blog.Dubstep

The XXX underground Music Venue. PHOTO CREDIT: Blog.Dubstep

Asia Art Tours:You mention in your book that when you left the international schooling system and went to public school in Hong Kong you became a ‘local’. Could you explain how, in Hong Kong’s elitist international schools, the term ‘local’ was used as an insult?

Karen Cheung: There isn’t really a consensus as to what “local” means. Like “Hong Konger,” it has no stable definition and is, like all identity-markers, a construct. You can read “Hong Konger” in an affirmative sense, take it as a term to mean the sense of community you share with the people around you; you can also, if, say, you’re a person who has felt like you are unable to belong to the city, give it a paranoid reading and believe that it’s real intention is to exclude you. (And that could be completely valid—especially if you’re someone who grew up as a minority population in Hong Kong / aren’t ethnically Chinese).

There are legal ways you can construe this, such as our nationality laws; I ran into an old flatmate recently, and the first thing she said to me was, “Hey, so I’m officially Chinese now,” and we both just stood there laughing for a minute, because she’s a Bengali Hong Konger—she had to naturalise for citizenship. In the specific context of the book, “local” was used on me, and my public school classmates, in the mid-2000s as an insult that suggested we were not worldly, not belonging to the upper-middle class, the global elite.

But it’s still used by expats as a synonym for “the Hong Kong people,” almost as though they’re acknowledging the different worlds that they live in within the same city; the locals don’t call themselves locals; they’re just existing. It’s a very othering term in a sense, and because of that more negative character traits are attributed to being “local” than positive ones; it’s not something to aspire to. Localism is something else entirely—it’s more about the question of whether there is a distinct enough culture to set Hong Kong apart from China.

I’ve always tried to frame these questions, at least for myself, in terms of belonging and community rather than “identity” or within ideological lines, especially when “left” and “right” has taken on so many varying meanings across the history of the city. If “local” is helpful insofar as it allows you to seek out a community that keeps you grounded amidst a prolonged resistance against the state, then maybe it’s still worth having around. If you can’t think of it as anything but a way to group people together under a set of characteristics in a way that’s lacking in nuance, then maybe not.

The ultimate goal should be to actively expand this category so that people who want to claim this label would be able to do so—it should be a term that encourages, rather than discourages, belonging.

“Local”, it’s still used by expats as a synonym for “the Hong Kong people,” almost as though they’re acknowledging the different worlds that they live in within the same city; the locals don’t call themselves locals; they’re just existing.

Harrow International School, one of Hong Kong’s many training sites for the offspring of the global ruling class. PHOTO CREDIT: Wikipedia

Asia Art Tours: For your international school classmates who belonged to the global ruling class, how does their desire to be ‘everywhere and nowhere’ ’impact the cityscapes of places like Hong Kong? What would a cityscape designed for ‘locals’ look like compared to the ‘global’ cityscape Hong Kong has now?

Karen Cheung:Even though I spend a lot of time talking about international school kids in the book, it’s really a way for me to explore these issues of superficial engagement with a place, of treating Hong Kong like nothing but a capitalist playground, of failing to acknowledge your responsibility to the community around you, that aren’t unique to them—it also comes up with expats, or 港豬—what we call “Hong Kong pigs”.

If you can’t see a place beyond its physical attributes, the food or the landscape or the hikes, then you won’t have an incentive to make things better when the fun disappears. I don’t know if the cityscape will necessarily look different, but I’d like Hong Kong to be seen as less of a disposable place.

I’d like Hong Kong to be seen as less of a disposable place.

Lan Kwai Fang, one of Hong Kong’s expat hotspots. PHOTO CREDIT: Wikipedia

Lan Kwai Fang, one of Hong Kong’s expat hotspots. PHOTO CREDIT: Wikipedia

Asia Art Tours: For Hong Kong’s protests, the dreams were big (democracy, abolition, decolonialism). When these ‘big’ dreams were destroyed by the state, are the small acts of solidarity that sustained those dreams left in everyday society? And if neither is left (Big Dreams or small solidarities), what is?

Karen Cheung: I don’t know if this answer is helpful for other people, but I’ve always been someone who’s sustained by my friendships, which in a way, is even smaller in scale than small solidarities with strangers on the street.

There’s not even really much of an underground movement any more, but there are community spaces where you can go to and you know you’d be surrounded by people who understand—bookstores, restaurants, etc. So long as you have one friendly face around you that’s still here, still trying—then nothing’s ever over.

Dreams that are killed off can be revived; sometimes it’s a matter of time. The real difficulty is that the protest movement was a very straightforward way for people to seek out those friends and friendly faces, especially when they may not have lived amongst those types of communities to begin with, and now there are fewer opportunities for people to be integrated and introduced to others who could still help them feel close to the city in these times.

So long as you have one friendly face around you that’s still here, still trying—then nothing’s ever over. Dreams that are killed off can be revived; sometimes it’s a matter of time

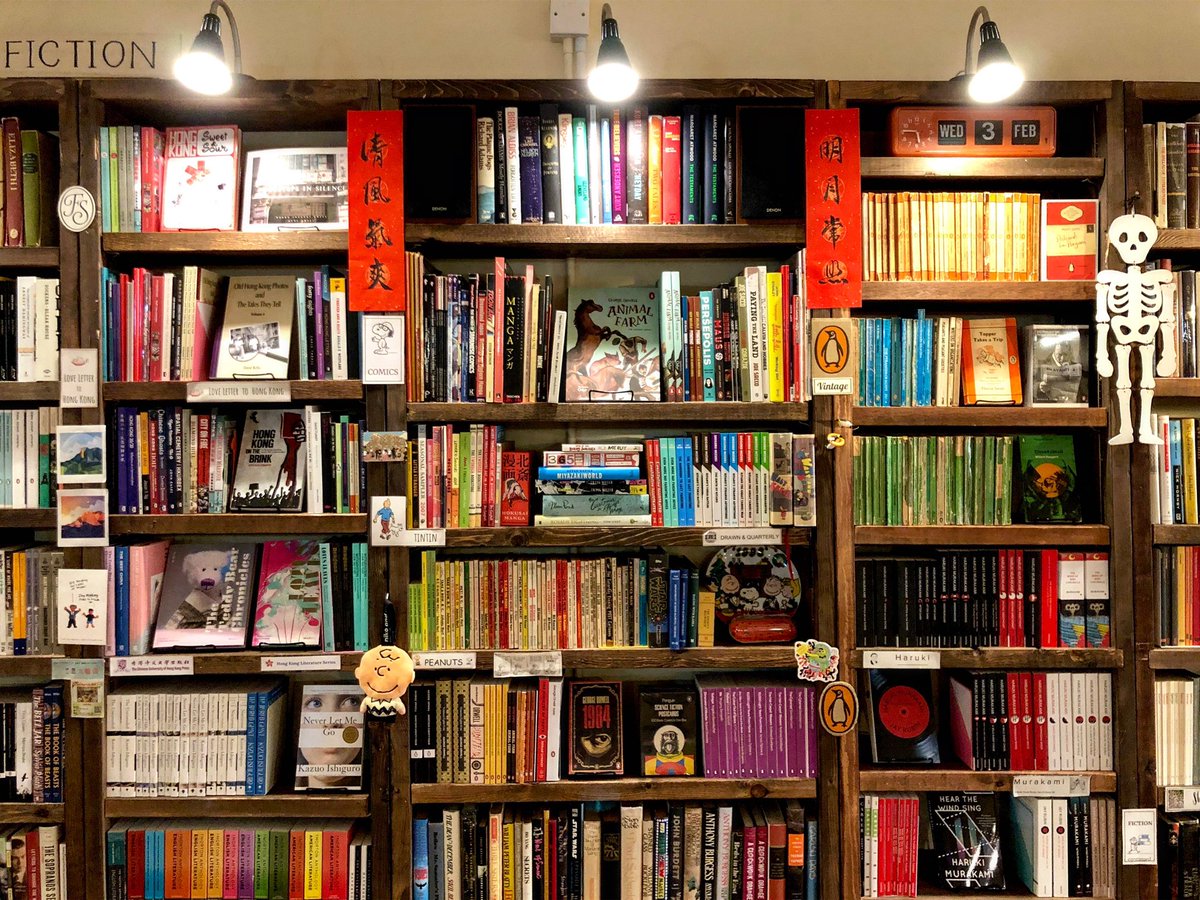

The fiction section of the now-shuttered Bleak House Books.

The fiction section of the now-shuttered Bleak House Books.

Asia Art Tours: You profiled the musician & “gentle anarchist” Leung Wing Lai, writing :

Lai said. In a city, art bore an inevitable responsibility to serve as a method of resistance: “Sometimes, if you’re talking about the responsibilities that a band has, that’s too grand of a topic for them to tackle. It might be impossible to ask them to go protest, but organising a show together—that’s possible.”

“And from this, we learn more about issues to do with space, public power, or ask ourselves questions like… Why do you have to ask me to leave? Why must I apply for a license to play here? A lot of discussions begin there.”

Reflecting on Lai’s words, what advice would you give for both Hong Kongers and global citizens under authoritarian rule about how we can build spaces that inspire questions? And what types of questions should we be asking?

Karen Cheung: I remember a piece by Masha Gessen in the New Yorker about why the dissident activist Alexey Navalny returned to Russia even after he was poisoned by the regime; Gessen argues that dissidents chose exile over staying in Russia because they had believed Soviet totalitarianism would last forever.

But for Navalny: “Putin, who became prime minister in August, 1999, and President at the start of 2000, has held power longer than any Soviet leader except Stalin. Yet Navalny, who was fifteen years old when the Soviet Union collapsed, understands that Putinism will not last forever…[Navalny] is not certain he will live to see a post-Putin Russia. But he believes that Russia after Putin will be—or at least can be—a fundamentally different place.”

Not everyone is going to have this type of mental fortitude, of course. Still, I think this brings up some important questions: How long are you willing to wait? And where do you want to be in the meantime? How does your choice reflect what you stand for, and how do we can make each day less terrible for the people we love, whether here or in exile? These are the questions I ask myself.

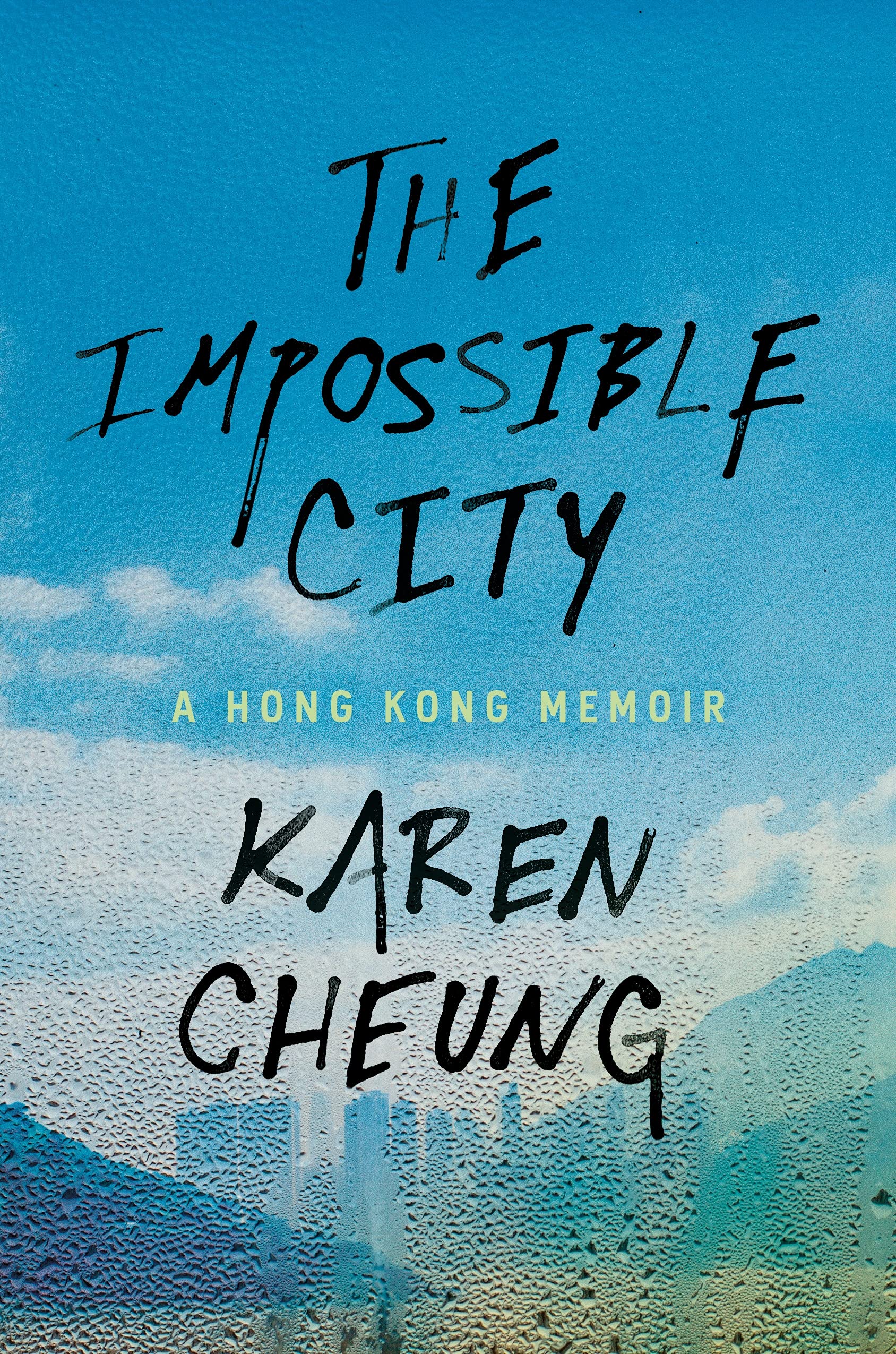

The Impossible City: A Hong Kong Memoir, can be purchased on Bookshop and other booksellers: https://bookshop.org/books/the-impossible-city-a-hong-kong-memoir/9780593241431

For more on the author, visit her website here: https://www.karen-cheung.com/