CONTENT WARNING: This interview is not suitable for those under 18. It contains frank dialogue on sexuality.

We spoke to Robert Yang on creating queer video games. Robert’s most recent game, We Dwell in Possibility, has been praised by numerous critics for its mix of the erotic and utopian. We discuss this and several other topics in our conversation below!

Asia Art Tours: Recently, I’ve become more interested in the anti-capitalist potential for video games. Broadly speaking, what thoughts (if any) have been on your mind related to the anti-capitalist potential of Video Games?

Robert Yang: I usually use the word “noncommercial” to describe my games. Generally I think being “anti-capitalist” requires doing a lot more political work than 99.99% of video games are capable of, including my own games.

Play-through from Robert Yang’s “Dream Hard” game. The game’s premise is the player “Must defend the local NYC queer performance space The Dreamhouse from hordes of fascists.” Video Credit: ROBERT YANG

Asia Art Tours: And when it comes to making political critiques through the medium of video games, do you favor a more abstract approach (such as the pay to play ‘Untitled Goose Game’?) or a more direct and confrontational expression of anti-capitalism (such as the free to play game ‘You Are Jeff Bezos’)?

Robert Yang: I’m probably halfway between these approaches. I want to name and critique political forces directly, but I also want politics to be just one layer or facet of it.

I can only speak in generalities here… The mainstream game industry often expects us to assimilate into the culture. Gay people are expected to be “not too gay”, women are supposed to be “cool girls”, people of color must code switch into some sort of inoffensive “neutral ethnicity”, etc.

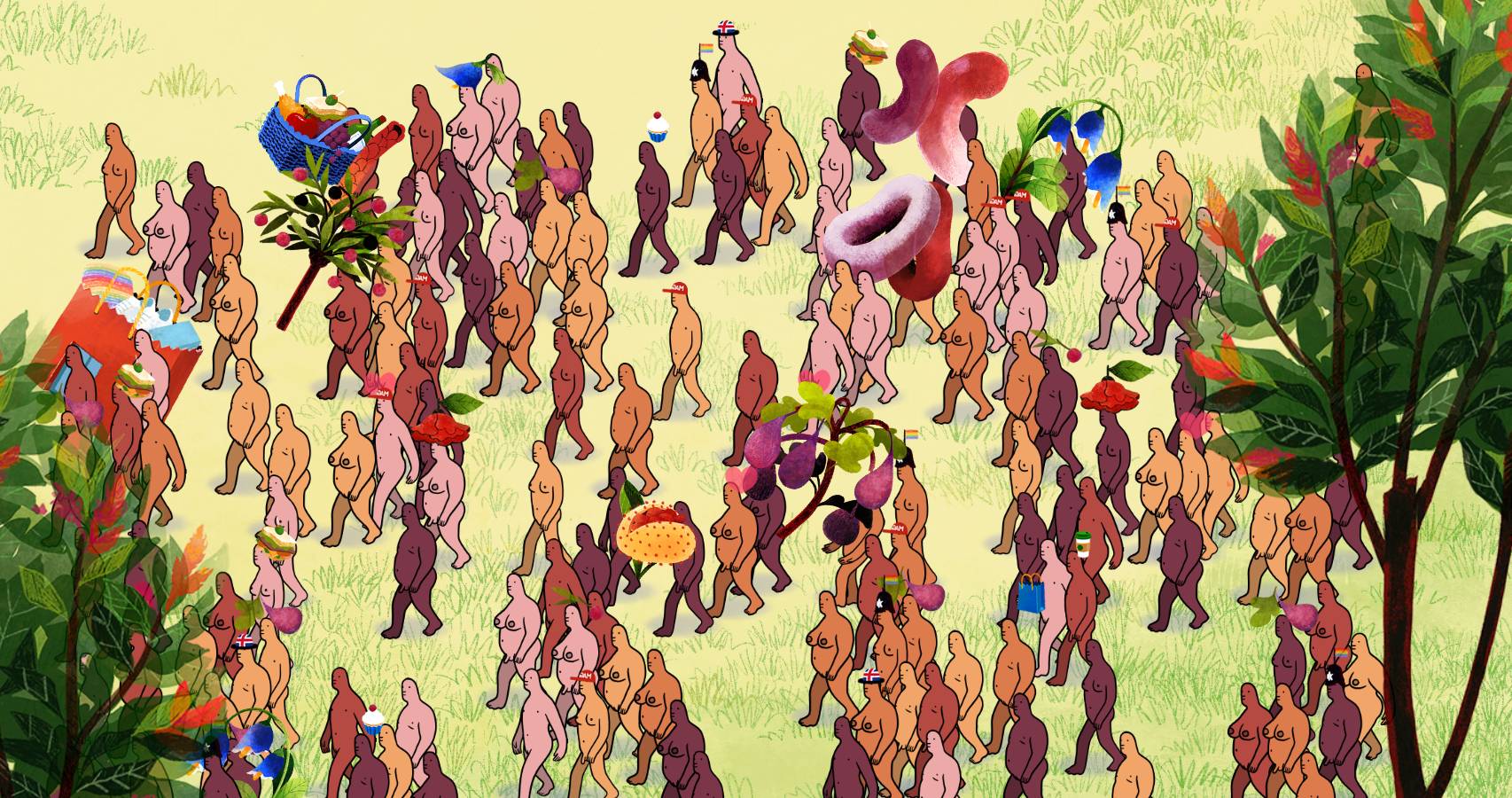

Artwork from Robert Yang’s most recent game: We Dwell in Possibility. Art by Eleanor Davis. Photo Credit – ROBERT YANG

Artwork from Robert Yang’s most recent game: We Dwell in Possibility. Art by Eleanor Davis. Photo Credit – ROBERT YANG

Asia Art Tours: The misogynistic and transphobic structural violence in the gaming industry as well as the profit large gaming studios derive from large right-wing contingents of video game players is well established. I know far less about what challenges gay game creators (or gay games) face.

If it’s not too personal a question, could you discuss what obstacles or structural prejudices you’ve faced from the video game industry as a gay video game designer?

Robert Yang: I can only speak in generalities here… The mainstream game industry often expects us to assimilate into the culture. Gay people are expected to be “not too gay”, women are supposed to be “cool girls”, people of color must code switch into some sort of inoffensive “neutral ethnicity”, etc. If we ever get invitations into the boys club, and have the gall to refuse or to engage with games in a different way, then the club feels offended and minorities become “ungrateful” problems to be dealt with. It’s a weird immature fragility.

Shame doesn’t come from eating the wrong fruit from the wrong tree, nor divine punishment for disobedience — shame is a social weapon, most commonly wielded by men against women.

Playthrough of Robert Yang’s videogame ‘Hard Lads’ based on an iconic viral video from the UK. Video Credit – ROBERT YANG

Asia Art Tours: And to put it bluntly, how does the video-game industry currently encourage or find profit in homophobia or queerphobia?

Robert Yang: As in many industries, game companies often “rainbow-wash” their corporate image to seem accepting and inclusive, while committing near-zero actual resources to supporting gay and queer developers / creators. Every June I have to sit and watch Twitch.TV put rainbows all over their website, even while they ban my gay games by secret tribunal with zero communication, explanation, or discussion. Today’s homophobes aren’t just moustache-twirling bigots — they’re also so-called “liberal” people who enforce homophobic policies, and reassure themselves that they’re just following orders. Keeping conservative men happy is more important than justice to them.

Characters from Robert Yang’s Videogame: Radiator 2. Photo Credit – ROBERT YANG.

Characters from Robert Yang’s Videogame: Radiator 2. Photo Credit – ROBERT YANG.

Asia Art Tours: I first reached out to you after playing your game, We Dwell in Possibility. The artwork, sexuality and nature aspects of the game reminds me of Hebert Marcuse and a term I’m writing an essay on, (what I call) ‘Green Abolitionism’.

For you or the co-creators you worked with on the game, how did you see sex connect with nature?

Robert Yang: Here I’m inspired a lot by John Berger’s Ways of Seeing, where he makes a distinction between nakedness and nudity. When something is naked, it’s simply present, revealing its own truth. When something is nude, he argues, it is objectified under an external gaze, often without consent. It’s valid to quibble with Berger’s word choice — personally I actually like the word “nude” — but I think the distinction itself is still useful. It aligns consent with self-identity and nature. And hopefully that’s reflected in the game — the AI peeps exist in their own bodies for themselves. Shame doesn’t come from eating the wrong fruit from the wrong tree, nor divine punishment for disobedience — shame is a social weapon, most commonly wielded by men against women.

As in many industries, game companies often “rainbow-wash” their corporate image to seem accepting and inclusive, while committing near-zero actual resources to supporting gay and queer developers / creators.

Game items and tokens from We Dwell in Possibility. Art by Eleanor Davis. Photo Credit – ROBERT YANG

Game items and tokens from We Dwell in Possibility. Art by Eleanor Davis. Photo Credit – ROBERT YANG

Asia Art Tours: And how do you see this ‘desire as utopia’ framing of We Dwell in Possibility in comparison to the desires your characters express in earlier, urban-centric games like Cobra Club or Hard Lads?

Robert Yang: Most of my games are about a few people, while WeDIP is about many people existing together in varying states of harmony / tension. Maybe it’s easier to narrow your world in a smaller built environment, while a natural setting encourages you to think about your wider context and bigger possibilities.

I agree about the importance of desire. How do we make people care about a climate crisis and its injustice? It’s hard to think your way into caring about something. And I like how sexuality often exposes the limits of intellectualization. It’s possible to think about your sexual desires for your entire life, and still barely understand what you really want

Playthrough from Robert Yang’s Game of ‘auto’-eroticism, Stick Shift. Video Credit – ROBERT YANG

Asia Art Tours: To end on a speculative question, like Marcuse I think we need to radically eroticize many of our contemporary social movements. The grim language of doom or dull technocratic language of most climate or progressive activists, I don’t feel helps us envision a utopia. To escape capitalism, patriarchy, racism, and all other forms of structural oppression, I believe we need desire, both for our politics and for each other, to be at the heart of our social movements.

How do you see sexuality as important to radical politics? And in We Dwell in Possibility are you trying to let players experience a vision of what sex and desire under utopia looks like?

Robert Yang: I agree about the importance of desire. How do we make people care about a climate crisis and its injustice? It’s hard to think your way into caring about something. And I like how sexuality often exposes the limits of intellectualization. It’s possible to think about your sexual desires for your entire life, and still barely understand what you really want. So if we’re talking about the future, then maybe the most important thing is to just really want anything at all. Yet who doesn’t feel alienated / tired / resigned about the world right now? Personally that’s where I’m at too. I like *thinking* about utopia and possibility, but day-to-day it’s hard not to *feel* like maybe it really is the end of history.

For more of Robert’s work and video games check out his main website: https://debacle.us/