I spoke to Atlantic and New Republic contributor Shaan Amin for a wide-ranging conversation on how comics and YouTube are being pulled in radically different directions by fanbases on the left and right.

In our conversation we discuss the progressive YouTube creators known as ‘Lefttube’, The domestic India Manga ACK, and how the ultra-popular comics SAGA and Attack on Titan are interpreted by the Left and Right.

Asia Art Tours: Just as we see a disconnect between the soaring stock market and the crushing reality of ordinary workers during Covid-19 in the US, I’m curious if there is also a cultural disconnect in media. As just one example, cop shows/superhero movies are being churned out in the era of the US’s largest police protests. In TV, Movie or Music, the world continues on under ‘Capitalist Realism’ while we stumble through the neoliberal ruins of unprecedented pandemic, poverty and anger.

Do you also see this bizarre contradiction and if so what do you make about the cynical reality of being ‘entertained’ during this small apocalypse? What might media that accurately reflected America’s lived experience at our current moment, look like?

Shaan Amin: This is a really good question. I suppose the first thing to point out is that in response to mass mobilization against the police, we’ve witnessed mass counter-mobilization supporting the police: Blue Lives Matter, the Thin Blue Line, and the Punisher skulls littering their ways across car bumpers and backyards. So, for much of the population, there is zero contradiction.

In your question, I’m hearing a few Brechtian ideas: epic theatre, dialectical theatre, art that should reflect real life to the viewer and rouse them to action. There’s an urgent need for such work. I do think we see tons of artists channeling their anger into craft and receiving wide traction for this. Ava DuVernay, Jordan Peele, and Riz Ahmed come first to mind. This kind of art makes us laugh and cry and get up in a rage to protest and join the picket line. And of course, there’s the smaller stuff: everything that’s coming up in the small presses, the zines, in different pockets of the Internet.

That said, life is hard, and I’m not really one to begrudge people who want to veg out after another day in Quar. Part of it is self-motivated, as I watch a lot of trash. I could defend it as politically necessary with the language of “radical self-care,” but to be honest I think the point of art is aesthetic at the end of the day. Art is political, sure, but art is also entertainment.

(Natalie Wynn of ContraPoints, one of the most popular media personalities within ‘LeftTube’- Photo Credit: YouTube)

(Natalie Wynn of ContraPoints, one of the most popular media personalities within ‘LeftTube’- Photo Credit: YouTube)

Asia Art Tours: Turning now to your work, I’d like to first discuss your article on Left-Wing Youtubers for the New Republic. We’ve had three mass left-leaning movements recently: The Bernie Sanders Campaign, Black Lives Matter and (broadly speaking) the mixture of ANTIFA & Mutual Aid organizing that’s coincided with Trump/Covid.

For ‘Left-Tube’ (or ‘Bread-tube’), did we see their media have a direct effect or influence on pushing people out into the digital and into real-life participation? And beyond the types of political action that are tolerated by the ruling class (voting and charity), was direct action supported by these content creators?

Shaan Amin: I’ll answer the second part first. The left in this country has never been a monolith. Lefty creators on YouTube are no exception. Some of the bread-ier Breadtubers make straight-up agitprop, and many others advocate disruption and protest: what we might call contentious politics. Other creators aren’t as interested in that. ContraPoints, for example, has staked a lot of her recent work about aesthetics and her interrogation of different facets of trans identity. Interesting, vital, and provocative, but rarely a direct call to action.

In any case, I don’t really know what causal effects this media has on people’s real-life participation. The people in comments sections who refer to changed hearts and minds provide some clue that this may shape politics of everyday interactions, but I think this is the kind of topic where research would be valuable. I’ve had a few ideas here or there, but no idea if I’ll get around to it.

Asia Art Tours: You mention the contradiction of trying to build leftist media on a platform owned by Google:

While LeftTubers find capitalism flawed at best and broken at worst, none felt deep personal tension between their politics and their presence on YouTube, an arm of the corporate leviathan Google. All of the LeftTubers I interviewed rely on their YouTube channels as their main source of income, either through Patreon donations, account monetization allowing ads to appear in their videos, or both.

This strikes me as the same failed ‘changing institutions from the inside’ cliché ; joining a group for/by elites then promising radical change for the many. Can these YouTubers disprove Audre Lorde’s maxim that ‘ The master’s tools will never dismantle the master’s house’? Or do you also see structural obstacles that will prevent these YouTubers from being anything more than ‘entertainment’?

And If there are structural barriers, are more leftist content creators moving to alternative models (such as Mastadon or Kolektiva)? Where might we see creators sacrifice revenue, for the chance, however small, of participating inside a more revolutionary institution than Google?

Shaan Amin: We’re getting in deep! I think there’s a distinction we want to make here. The idea of kyriarchy is valuable because it helps us see how domination and oppression intersect and interact, but we shouldn’t forget that any corporate actor has its own interests. Will Google’s tools dismantle Google’s house? Unlikely: see how they sacked Dr. Timnit Gebru. But could Google’s tools dismantle other masters’ houses? If Google has more to gain than to lose from it, the odds suddenly seem better.

(The firing of Dr Timnit Gebru outraged many in the tech community. However, besides Silicon Valley critics like Wendy Liu or Edward Ongweso Jr. , few are discussing if beyond reform certain institutions, like Google, need to be broken up or abolished entirely. Photo Credit: Wikipedia)

(The firing of Dr Timnit Gebru outraged many in the tech community. However, besides Silicon Valley critics like Wendy Liu or Edward Ongweso Jr. , few are discussing if beyond reform certain institutions, like Google, need to be broken up or abolished entirely. Photo Credit: Wikipedia)

As for other models, I think you’re more aware than me. In general, I’m pessimistic. This is a paradox of the information age. There is more content being generated by more people than ever before, but we need a way to sift through it and find it. Boom, we have algorithms built by people with biases. If something is decentralized, how do we keep it democratic, fend off the trolls, and combat misinformation? One thing that interests me more is the potential of alternative ownership structures. How do worker-owned tech companies and non-profits perform in this space? What could they do, if properly resourced? The Wikimedia Foundation gives us one example of an incredibly successful non-profit. I’m sure there are experts in this matter. I’m not one of them.

Asia Art Tours: Turning to your piece in the Atlantic on ACK, perhaps India’s most popular home-grown comic, and one that explores Hindu’s canon, here is how you discuss ACK’s impact on yourself as a young reader:

Since its debut in 1967, ACK has also helped supply impressionable generations of middle-class children a vision of “immortal” Indian identity wedded to prejudiced norms. ACK’s writing and illustrative team (led by Pai as the primary “storyteller”) constructed a legendary past for India by tying masculinity, Hinduism, fair skin, and high caste to authority, excellence, and virtue. . . The heroes of ACK became my superheroes long before I discovered Spider-Man or the Flash. They also became my first window into a culture I barely knew. I didn’t care that the protagonists I was reading about were drawn with white skin. I was unaware of the broader, ongoing effort by Hindu nationalists to define a doctrine devaluing lower castes, women, tribal populations, and religious minorities.

India is now controlled by the BJP and RSS, groups that have a Hindu supremacist agenda. You speak of the many prejudices within ACK, I wanted to ask where we might see the same prejudices within the BJP Party? Conversely, where would we see push-back to the visions of Hindu supremacists within ACK?

And would ACK’s audience be one that represents the pluralities of Indian society of class, caste and religion? If not, would there be other comics that fill the role ACK does for Hindus?

Shaan Amin: The BJP is rife with these prejudices. Their Islamophobia manifested in the atrocities of the blacked-out Kashmir occupation and the Citizenship Amendment Act. Their disastrous demonetization scheme in 2016 speaks to the BJP’s callous disregard for its vulnerable citizens and its incompetence in managing the economy. But it’s important to recall that there are no innocent parties in India. These prejudices are echoed in the Congress Party and various smaller parties.

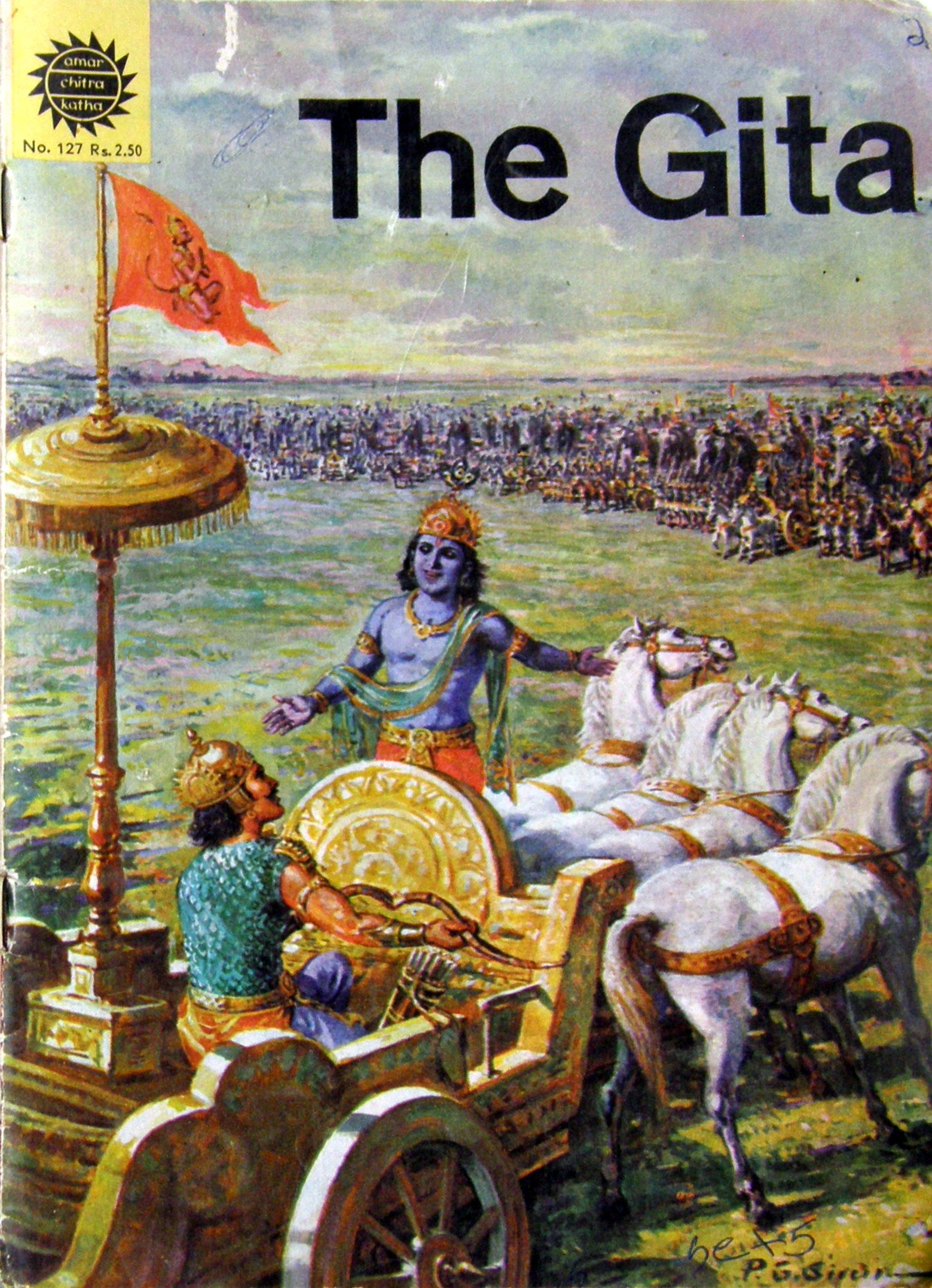

(India’s domestic comic series Amar Chitra Katha or ACK chronicles the Hindu Canon in a way that has profoundly affected millions of fans. Though there have been many controversies during its history. Photo Credit: Wikipedia)

(India’s domestic comic series Amar Chitra Katha or ACK chronicles the Hindu Canon in a way that has profoundly affected millions of fans. Though there have been many controversies during its history. Photo Credit: Wikipedia)

I think ACK has the potential to push back against the worst excesses of Hindu supremacy. The series does offer examples of exceptional women, low-caste figures, and Muslims. ACK’s issue on Ambedkar explicitly notes that Ambedkar led mass conversions to Buddhism to escape the caste system. That said, the series as a whole tends towards erasing non-Hindus and sanitization of history do align with these prejudices.

I don’t know too much on the broader sphere of comics in India, so I can’t speak too much to the readership of the comics. I will say that a pretty ticked-off wave of people came at me online, saying that this piece was a hit job on ACK and Hinduism. I’d like to think they aren’t representative. I think that reaction says a lot about the fragility of a pocket of the audience. Indeed, I found the virulence of this response much more unnerving than the comics themselves.

Asia Art Tours: I’d like to bridge our discussion on ACK with your article in the Atlantic on Saga. You write: Since Saga is a comic series, it’s worth starting with the art: Staples’s illustrations hold a particular power even viewed apart from the narrative. In science fiction, as in most genres, white masculinity is the cultural default. Some people bound to those norms have viewed deviations—for instance, a black Stormtrooper in Star Wars or an Asian woman captaining a starship in Star Trek: Discovery—as millennial pandering at best, or “white genocide” at worst. Yet as Vaughan has recounted in interviews, Staples’s first question when he pitched the main couple to her was, “Well, do they have to be white?” The artist went on to model Alana as a mixed-race, dark-skinned woman and Marko as an East Asian man, though both are aliens.

How does Saga handle Race in the future? Does it cement itself in our present understanding and prejudices or does it try to imagine a future that has diversity but lacks ‘race’ and all the state, supremacist and capitalist violence that attends to it?

Moreover, as fugitives, the main protagonists are prevented from becoming ‘citizens’, becoming ‘seen’ by the state and thus remain truly themselves… truly ‘human’. Do you see Saga as offering a critique of the ‘nation-state’s and the concept of defining ourselves as citizens? Where might we find peace in trying to escape this obligation that is forced upon us?

Shaan Amin: One of the wonderful things about Saga—and science fiction generally—is that it can explore race and ethnicity while not mapping them neatly onto our world. Saga doesn’t take place in our galaxy, and if I recall correctly, skin color doesn’t have the same resonance as it does in the United States. However, the ethnic prejudice between the people from various worlds is all-too-familiar, as is the way in which the war between two powerful nations crushes others in its wake. In that way, it creates magic: liberating bodies by reimagining a context without our stigmas, then interrogating the nature of oppression by adding brand-new stigmas. It’s genius.

(Panels from the Comic SAGA – Photo Credit: Wikipedia)

(Panels from the Comic SAGA – Photo Credit: Wikipedia)

I can see a case for Saga as a critique of the nation-state generally, though to me it seems more directly a critique of violent nationalism. I think that one of the most powerful and tragic things about Saga is that the universe refuses to let Alana and Marko escape the political implications of their relationship. One is a conscientious objector and the other is a deserter, but neither are activists. The characters would rather the war ended, but they aren’t trying to end the war. Their very existence, though, is a threat. In that way, Saga speaks to the fragility of the people who promote jingoist ideologies. If a Black man kneels during a football game, then America will surely descend into chaos. If an interracial couple has a child, then the war effort will surely collapse.

Asia Art Tours: To conclude, I’d like to discuss your New Republic article on Attack on Titan, the Manga has global popularity with both progressives and (unfortunately) with white nationalists.

You write: The range of audience responses serves as a reminder of people’s tendencies to sift through stories to find the messages they expect. Liberals are not immune: As a left-leaning fan of the manga and show, I read it as a metaphor for anticolonial revolutions and the struggle of building postcolonial states after years of exploitation. White nationalists, bereft of a conflict beyond grinding away the rights minority groups possess, must look to fiction—QAnon conspiracy theories, Attack on Titan, myths of white genocide—to invent a struggle in which they can participate.

This reminds me of the horror Pepe the Frog’s creator had at his work being adopted by the Alt-Right (he eventually killed off the character). Beyond the particular affinity the Alt-Right has for AOT, is this generally speaking how Fascism works its way into mainstream discourse? By growing like a mold on media that normally would reject it or have nothing to do with it originally? If so how can creators do a better job distancing themselves from their fans?

You mention the anti-colonial reading you had of Attack on Titan, is there room for an ‘Anti-Capitalist’ reading as well? I see the Titans coming into the walled city to destroy its inhabitants the same way I would see a Wall-Mart, Amazon, Samsung or Sony coming into ravage local communities. And be it an anti-colonial or anti-capitalist what tools or advice does Attack on Titan have on resisting ‘monstrous’ forces far larger than ourselves?

Shaan Amin: People much better-informed than me have spilled tons of ink on how fascism normalizes itself, but in Attack on Titan’s case, the white supremacists lurking on 4chan were growing out of sight of the mainstream media. As far as I know, my piece is the first one that actually went into the alt-right discussion boards, rather than just doing media analysis. The alt-rights pockets of the web are a whole ecosystem, self-sustaining and proliferating. Mainstream rejection may have once constrained the growth of these sentiments, but it couldn’t make them die off. And now, we’re living in a time where QAnon is a fairly common belief in the Republican base.

I don’t know what the responsibility of an artist is in these times. I tried to write a meditation on death of the author in the time of chan-boards, with Attack on Titan as a case study. Authorial intent is tricky and declaring a piece of media “woke” or “not woke” is often complicated. (Admittedly, sometimes it’s very straightforward.) It’s easy and largely costless to disavow Nazis, but I have other questions. Do we want artists to do this to reassure us that they’re okay people, or to send a message to fascists that fascism is bad? When and how does art have the ability to deradicalize people, not just call them out? How much of this is incumbent on individual artists? I grew up in a very conservative Rustbelt area. That makes me a cynic in many ways, but it also makes me not want to give up hope in the power of redemption and other deprecated concepts.

(Panel from Attack on Titan – Photo Credit:Wikipedia)

(Panel from Attack on Titan – Photo Credit:Wikipedia)

But let’s end on a happier note. That’s the first time I’ve heard an interpretation of Attack on Titan of Titan as giant multinational conglomerate, but I think it’s cool! I’d refer you back to Hajime Isayama, “Being a writer, I believe it is impolite to instruct your readers the way of how to read your story.” So theorize away. Thanks for inviting me, and thanks for the thought-provoking questions.

For more w. Shaan Amin, please read his work on the Atlantic or New Republic. You can also visit his main website here -> https://shaan-amin.github.io