We had the rare opportunity to interview legendary Dr. Shinji Yamashita. He is the Professor Emeritus of Anthropology at the University of Tokyo. If “Eat Pray Love” was a godsend to luxury travel in Bali, Dr. Yamashita’s work stands in opposition to the commodification of Bali’s culture and informs us how First World travelers and big business often change cultures to fit the narrative of what they want that culture to be.

We spoke with Dr. Yamashita about Japan, Bali, his Academic Work and his thoughts on what we can do better in Tourism. I hope you enjoy our chat.

- AAT: May we put a story to the academic? Could you tell us a bit about your background and how you decided to get into Academia

- ——My background is cultural anthropology. Since student days, I have been interested in cultures in Southeast Asia, particularly Indonesia. I did my first fieldwork for my Ph.D. in Toraja, Sulawesi, Indonesia, in the latter half of the 1970s, where I came across the tourism which had been introduced to Toraja as a tool of development. After I finished my Ph.D. work, I developed my study of tourism in Bali and other places in East and Southeast Asia.

- Reading your work I love the clear, common, and direct explanations you use to report your findings. Could you tell us why you choose to make your writing accessible both for the people and the academy? And perhaps why many academics choose to use language that is inaccessible to those outside of the academy.

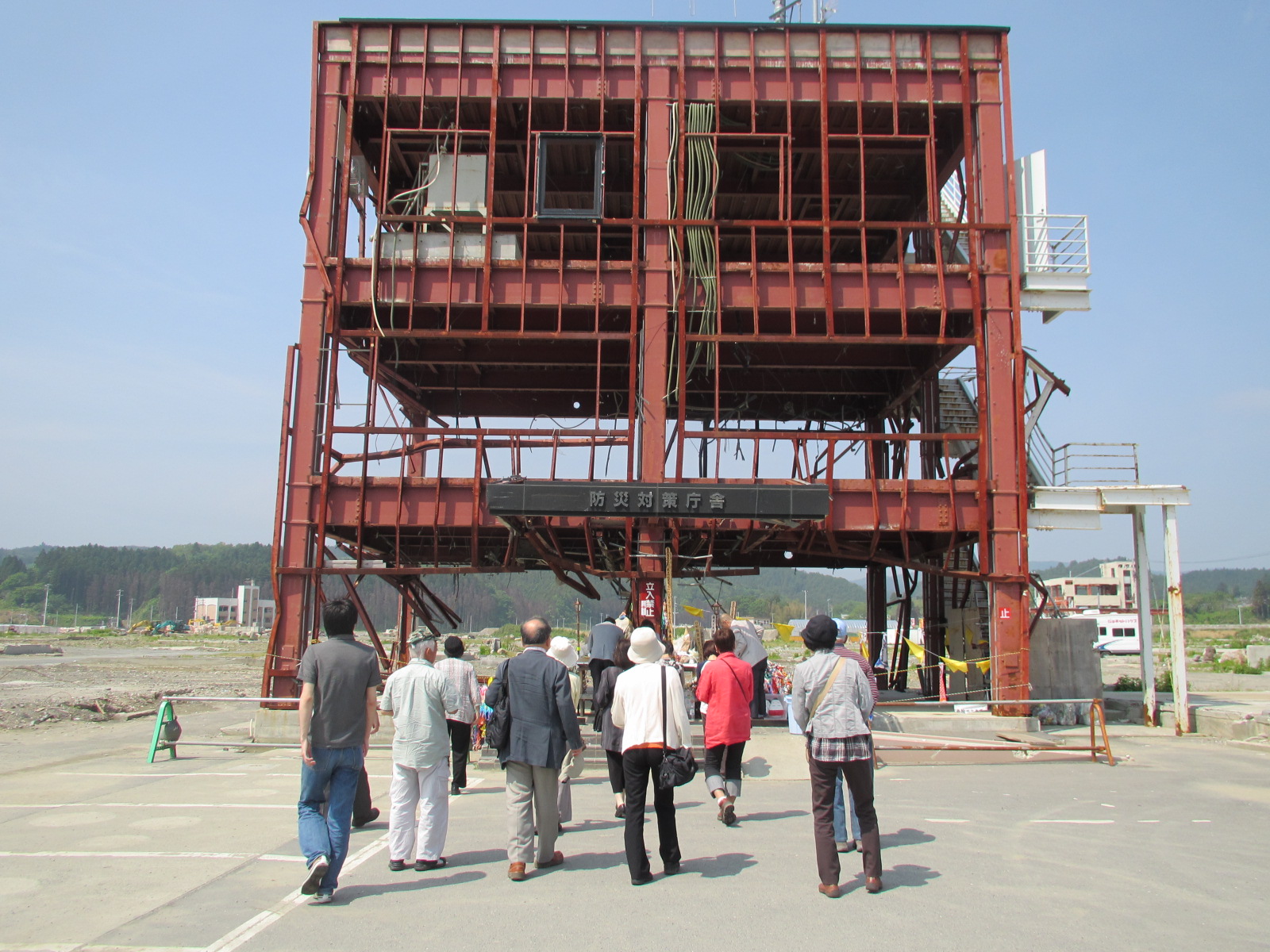

——The academy should be open to the public. From this point of view, recently I have promoted “public anthropology” so that anthropology could contribute to the analysis and solution of problems in the public domain. In the field of tourism, I have also proposed “public tourism” in which tourism is used as a tool to solve public problems. I practiced this in relation to the “disaster tourism” in the aftermath of the Great East Japan Earthquake which had occurred in 2011. This is my idea of how to link the academy to the public.

- (Photo of Disaster Tourism in the aftermath of the 2011 Japanese Earthquake- Taken by Shinji Yamashita)

-

- I noticed in your work that you cite both Eric Hobsbawm and Frederic Jameson. Broadly speaking, do you see Marxism and Postmodernism as phenomenon worth exploring or useful in explaining modern tourism? Why?

- ——In the 19th century Karl Marx attacked the question of modernity in which capitalism is a historical condition. Marxism may be still worth taking into consideration to explore tourism as a modern phenomenon (See Dean MacCannell’s work, The Tourist). While post-modernism is still a vague concept as an analytical tool, it raised new questions that lead us to consider the problem in the late modernity in which tourism is becoming increasingly important.

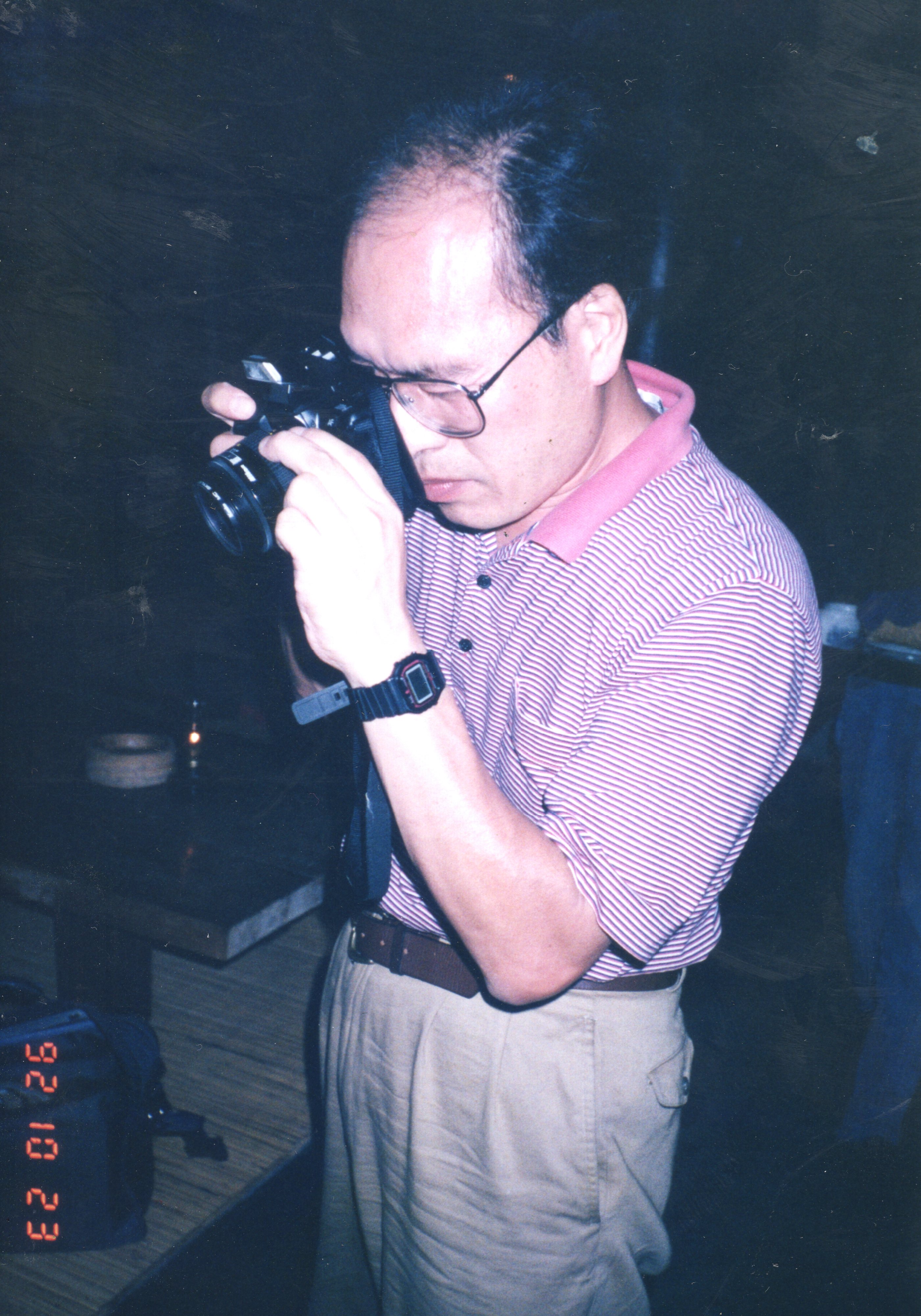

- I deal with many tourists pushing limits/violating cultural norms by taking photos or engaging with technology in sacred cultural spaces (funerals, temples). Could you tell us about your famous study of this Indonesian Funeral among the Toraja of Sulawesi. Why was Japanese media used to deliberately publicize this “sacred” space. And what does this event portend for the future of the “sacred” in the era of social media?

—— In the non-Western society, difference between the sacred and the profane is not so sharp. In Toraja, funeral is all at once a religious ritual, an economic enterprise, and a social event. Japanese temples and shrines have been linked to secular tourism sectors for a long time in the history. Taking photos is a crucial tourist behavior. There may be no tourists without bringing cameras. Taking photographs is, as Susan Sontag has pointed out, “a way of certifying experience but also, a way of refusing it, by limiting experience to a search for the photographic, by converting experience into an image, a souvenir” (On Photography). In the recent development of technology, “Instagram” has become a key word for tourism experience.

(Tourists at a funeral in Bali- taken by Shinji Yamashita)

(Tourists at a funeral in Bali- taken by Shinji Yamashita)

-

- You mention in Palau and Bali there is a tension for Japanese tourists that doesn’t exist for Western Tourists, between the pull of nostalgia (identifying with cultural similarities) versus the desire to make primitive or exocitize these cultures. In very broad strokes could you talk about what you find interesting or productive from this dialectic? And what is problematic (if anything) for Western Tourists who only engage with or perpetuate the framework of the “exotic”/ “other” when they visit similar destinations?

——It is interesting to see cultural differences of tourists. In the recent inbound tourism to Japan, there is a big difference between Asian tourists and Western tourists. Asian tourists, particularly Chinese tourists, like shopping, while the Western tourists love Japanese traditional culture.

- Building off Question 5, could you talk about what Balinese culture might have become had its culture not become commodified? What is the “Imaginary” Bali of tourism, who manufacturing it, why was it manufactured, and who benefits from an “imaginaries”?

——Balinese culture is also commodified in the contemporary global tourism. Modern tourism is a product of capitalism in which culture too becomes commodity. As I have discussed in my book Bali and Beyond, the “imaginary” Bali as ”the last paradise” was created in the 1920s and 30s through the intercultural communication between Bali and the West. Now ironically some say that Bail is still a “paradise” but a paradise of capitalism (!) under the mask of the touristic “imaginaries”.

-

- With the explosion of inbound tourism to Japan, how has Japan reacted to these attempts to package Japanese culture or Japanese ecosystems (landscapes) as exotic products to sell to foreign tourists? Is there now an “imaginary” Japan for tourists versus a “real” Japan for the domestic market and citizens?

—— This is not necessarily the case. I have already mentioned the cultural difference among inbound tourists to Japan. Each of them seeks for his/her “imaginary” Japan. What is interesting is that the tourism resources are not only “traditional” culture but also new culture like animation, manga, electric products, robot, ramen, drugs, and even the urban landscape of crowded crossroad of Tokyo. In this sense there is no sharp distinction between “imaginary” and “real” in the Japanese inbound tourism. Ordinary things for Japanese could become extraordinary for foreign tourists.

(Japanese Tourists in Kimono, Taken by Shinji Yamashita)

-

- How do you see ecotourism evolving in an era of ecological collapse?

—– Ecotourism should become an important tool to learn our environment which includes not only “pristine” and “precious” nature but also collapsed and polluted environment. The latter can be taken as “dark tourism.”

- (Dr. Shinji Yamashita preparing for field work in Bali)

-

- Likewise, in an era of globalization how do you see the concept of “authenticity” evolving for tourists and the travel industry.

- —– “Authenticity” is in my view the modern Western idea relating to the concept of “copy right.” In the “postmodern” philosophy, the concept of the original (and the copy) should be reconsidered. One example is the theme park like Disneyland where the copy has overtaken the original. In the field of tourism, “post-tourists” would not believe in the distinction of the authentic and the fake.

-

- I wanted to ask a question based on a academic you cite: “According to Kang Sang-Jung, Japan orientalism can be defined as being motivated by a desire to avoid Western Imperialistic violence and to use Japan’s own hegemonic power in the Asian and pacific Regions. “Japan needed the primitive and backward south to feel advanced and civilized itself. What was Kang Sang-Jung’s larger point in making this critique? And why do you think, in the face of outsiders, a Western-based or influenced society needs to feel ‘advanced’?

———– I have discussed this in relation to the development of Japanese anthropology (See Yamashita, “Constructing selves and others in Japanese Anthropology.” In: Shinji Yamashita, Joseph Bosco, and J.S.Eades, 2004, The Making of Anthropology in East and Southeast Asia. Berghahn Books). We should date back to the latter half of the 19th century to consider this problem. That was the age of social evolution in which the “civilized” Western powers colonized the rest of the world. In that situation Japan wanted to survive to catch up the civilized Western society, while colonizing the “primitive” South including Taiwan, Southeast Asia, and the Pacific. Then Japanese anthropology started to study Japan’s South as a “primitive” society.

-

- Lastly what hope or wisdom do you feel we can find in travel?

—–Travel is similar to anthropology. We discover the unknown world through travelling (doing fieldwork). In that sense tourism has become an important tool to learn about the world just like anthropology

Professor Shinji Yamashita is and Emeritus Professor of Cultural Anthropology and Human Security Program at the University of Tokyo and a former president of the Japanese Society of Ethnology (currently Japanese Society of Cultural Anthropology). His research focuses on the dynamics of culture in the process of globalization with a special reference to international tourism and transnational migration. His regional concern is with Southeast Asia, particularly Indonesia, Malaysia, and Japan. His books include Globalization in Southeast Asia: Local, National, and Transnational Perspectives (co-ed. with J.S. Eades, Berghahn Books, 2003), Bali and Beyond: Explorations in the Anthropology of Tourism (translated by J.S. Eades, Berghahn Books, 2003), The Making of Anthropology in East and Southeast Asia (co-ed. with Joseph Bosco and Jerry S. Eades, Berghahn Books, 2004), Transnational Migration in East Asia: Japan in a Comparative Focus (co-ed. with Makito Minami, David W. Haines and Jerry S. Eades, Senri Ethnological Reports 77, National Museum of Ethnology, Osaka, 2008), Kanko Jinruigaku no Chosen [The Challenge of the Anthropology of Tourism](Kodansha, 2009), and Wind over Water: Migration in an East Asian Context (co-ed. with David W. Haines and Keiko Yamanaka, Berghahn Books, 2012).