We spoke (separately) to University of Wisconsin scholars Tyrell Haberkon & Thongchai Winichakul on protest, organizing and state violence in Thailand. Dr. Haberkorn discusses the contemporary lessons of rural resistance in 1970s Thailand. Dr. Winichakul discusses ‘Hyper-Royalism’. You’ll find both conversations (as two separate interviews) below.

Asia Art Tours: I first reached out to discuss your important article in the New Mandala looking at the targeting of academics in Thailand. Could you discuss the current state of academic freedom in Thailand? What are the new ‘red lines’ that academics are facing?

Tyrell Haberkorn: Academic freedom in Thailand is under tremendous threat. This includes both the threats to individual academics like Nattapoll Chaiching, and his publisher and advisor, as well as the broader context of freedom of thought in Thai universities and secondary schools. What is most concerning is that since the 22 May 2014 coup by the National Council for Peace and Order, it has become very clear that the majority of university administrators are more likely to side with the authoritarian state over their faculty and students. They do so by passing on threats, engaging in their own intimidation, and encouraging self-censorship.

The invisible ‘red lines’ are not new – they have always been present and are always changing. One does not know one has crossed the line until the police or soldiers call the rector of a particular university, or drive by the house of a faculty member of student.

My sense is that the Thai state is afraid of dissident thought of all kinds and in all forms – whether it comes from an academic taking a rigourous perspective on the monarchy or a Grade 7 student who refuses to get the standard haircut.

Thai Students reenact the forced haircuts they are required to receive to attend school. Video Credit: Teirra Kamolvattanavith/ Twitter: @Teirrabyte

Asia Art Tours: From the perspective of the Thai State and/or Monarchy what does it find threatening about academia? Is this repression new or part of a long push-pull with the university?

Tyrell Haberkorn: My sense is that the Thai state is afraid of dissident thought of all kinds and in all forms – whether it comes from an academic taking a rigourous perspective on the monarchy or a Grade 7 student who refuses to get the standard haircut. This repression has always been present and what has now shifted is that there is a critical mass across different sectors of society that is unwilling to comply.

Asia Art Tours: In your book Revolution Interrupted: Farmers, Students, Law and Violence in Northern Thailand you often bring up the figure of the ‘organic intellectual’, for Thailand’s current democracy protests who are some of the organic intellectuals to have emerged? And what ‘education’ did they find within struggle /protest that was unavailable to them in state educational settings?

Tyrell Haberkorn: There are so many exciting organic intellectuals in the current protests. To name only a few – Somyot Prueksakasemsuk, Waddao Chumaporn Taengkliang, Arnon Nampha, Parit Chiwarak, Panusaya Sithiijrawattanakul, Panupong Jadnok, and many many more. Somyot is a long-time labor activist and writer who spent over seven years in prison after being unjustly convicted of violation of Article 112. He is very clear that his education comes from both years of working with workers and from fighting his case and being imprisoned. Waddao is an LGBTQIA+ and women’s rights activist who has worked to ensure that these issues are not at the margins of the democracy movement, but central. Arnon Nampha is a poet and lawyer who was one of the only lawyers to defend those accused of lèse majesté and various political cases following the April-May 2010 crackdown on red shirt activists. His poetry bears witness to what he saw and heard working as a lawyer for those unjustly prosecuted. In contrast, Parit, Panusaya and Panupong are part of the wave of youth activists who are pushing people to think differently about the monarchy through their courageous voicing of the questions which were only whispered previously.

One could think of all of these people as activists, rather than intellectuals – but I think the work they are doing through the protests they organize and the speeches they give is precisely the work of thought, and learning new ways of apprehending the present in the service of working towards a new future. [Translations of speeches by Arnon, Parit, Panusaya and Panupong have just been made available by PEN International]

To me, one of the most exciting aspects of the current democracy movement is its historical consciousness.

Dr. Haberkorn’s book, in the spirit of Raphael Lemkin or Angela Davis, examines if Thailand’s Laws can ever be used by the oppressed to pursue justice.

Dr. Haberkorn’s book, in the spirit of Raphael Lemkin or Angela Davis, examines if Thailand’s Laws can ever be used by the oppressed to pursue justice.

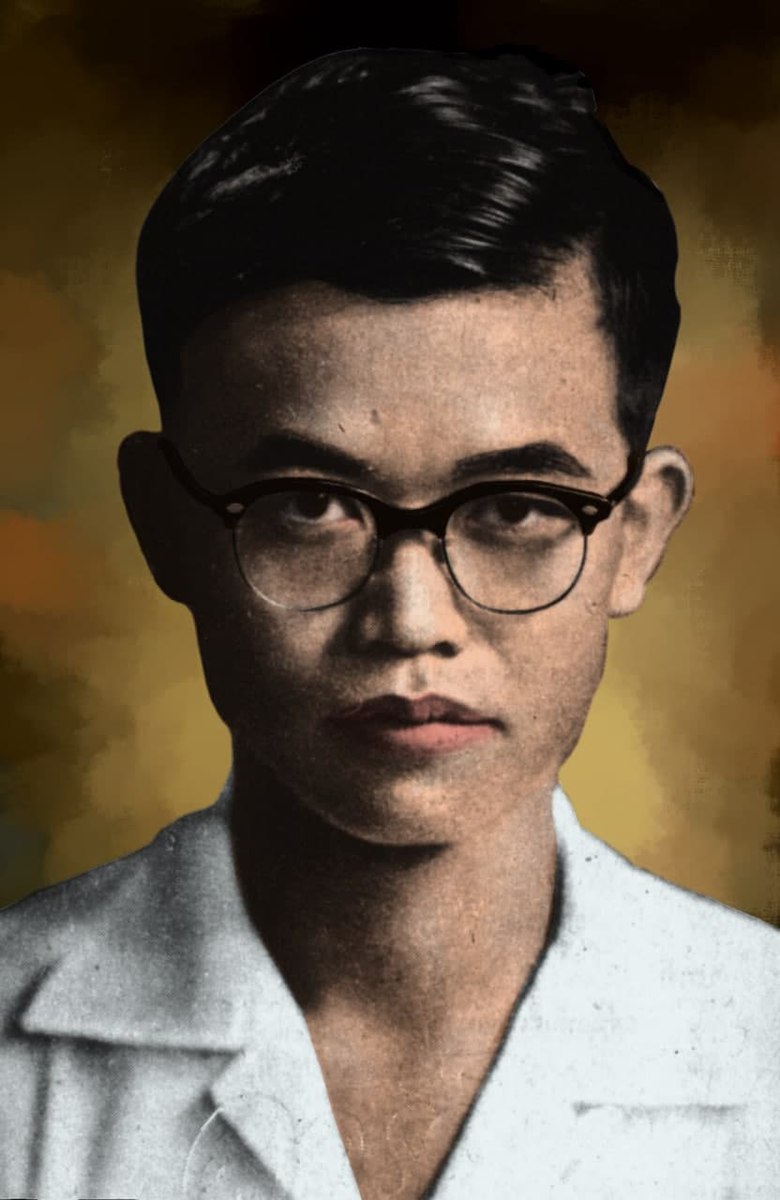

Asia Art Tours: Are the organic intellectuals of the present connecting to organic intellectuals and social movements of the past? And are Thailand’s democracy movements connecting with and learning from formal academics both past and present (such as Jit Phumisak) ?

Tyrell Haberkorn: To me, one of the most exciting aspects of the current democracy movement is its historical consciousness. This is evident in the dates chosen for protests – such as the anniversary of the end of absolute monarchy on 24 June 1932 – and in the speeches given – when activists place themselves within a trajectory. There are many links to previous intellectuals and figures, including Jit, of course, and also Pridi Banomyong, Khrong Chandawong, Nuamthong Praiwan, and others.

Asia Art Tours: In your book you examine The Farmers Federation of Thailand which chose to try to seek redress from the state by either demanding new laws or demanding the enforcement of existing laws on the propertied/landlord class. During this time there was also The Communist Party of Thailand – an armed resistance that refused to negotiate on the terms set by the Thai State / Monarchy.

Could you discuss who made up the ‘base’ of these two movements, And what vision of a ‘different’ Thailand did they offer to supporters not only through their grand political visions, but also through their (to quote Zizek) ‘revolutionary micropolitics’?

Tyrell Haberkorn: The two movements shared a base combined of students, workers, farmers, teachers, and many others who came to consciousness about the long-term injustice and entrenched inequality in Thailand. One key difference between the two is that the FFT was an organization that was formed in November 1974 and had largely gone underground [with many members joining the CPT] by late 1975, while the CPT traces its roots to regional organizing in the 1920s.

The FFT was led by a coalition of farmers throughout the country, working with students and workers [together, they comprised the sam prasan, or ‘three links,’ who together led progressive politics between 14 October 1973 and 6 October 1976] to advance concrete material improvements in the lives of landless and tenant farmers. One of the ways they did this was by pushing to pass and then implement the Land Rent Control Act. In the north, the work to implement the Land Rent Control Act was a key site of both daily struggle, and of imagining a different Thailand and a different future. The Act changed the material relations between landlords and tenant farmers, who often had to give 50% or more of the rice harvest as rent to the landlord, by reducing the rent. More significantly, the Act positioned both landlords and farmers as equal parties to determining the appropriate rate of rent in each district and populating dispute committees. Until that moment – and after that moment – the law was a tool that the powerful imagined belonged to them alone. One example of how ‘revolutionary micropolitics’ emerged are the actions of farmer activists learning about the law, often in collaboration with lawyer and student allies, and then educating their neighbors about it. Through this shared struggle, farmers, students, and lawyers – who were positioned differently vis-à-vis existing inequality – began to live the different future they hoped to see.

The CPT’s base, particularly after the 6 October 1976 massacre, included activist who had been active aboveground in the preceding three years. But the CPT also counted members of various ethnic minority groups, including the Hmong and Karen in the north, and longstanding communities of revolutionary fighters across the north, northeast, and south. In reflecting on the different future envisioned by the CPT, what I am most struck and moved by are the memoirs written by former CPT fighters. The work of uniting Marxist-Leninism and Maoism with the conditions of Thailand was difficult – and yet there was tremendous possibility within the building of shared struggle among those who came from the cities and those who firmly of the countryside. It was within those relationships of struggle that I imagine ‘revolutionary micropolitics’ came to life.

The law was, and remains, a tool of those who hold power in Thailand. The power they hold is so great that even when they act illegally – such as ransacking the prime minister’s residence or fomenting a coup – they can cast it as legal.

Lithograph of assassinated revolutionary academic Jit Phumisak. Image: CC 4.0

Lithograph of assassinated revolutionary academic Jit Phumisak. Image: CC 4.0

Asia Art Tours: In your book, you document the assassination of farmer leaders, as well as a police-led riot against the farmers movement that ransacked Prime Minister’s Kukrit’s private residence. But rather than these actions being seen as ‘against the rule of law’ it was instead the law-abiding farmers, who were labeled the ‘agitators’, ‘outsiders’ and ‘trouble-makers’.

Why were those who acted illegally considered ‘lawful’ and those who acted legally ‘lawless’? What forces and powers were at play that rewarded the police, landlords and far-right royalists for illegal methods, but punished the farmers for trying to resolve their differences with capital and the state through legal methods?

Tyrell Haberkorn: The law was, and remains, a tool of those who hold power in Thailand. The power they hold is so great that even when they act illegally – such as ransacking the prime minister’s residence or fomenting a coup – they can cast it as legal. Within such a world, when those who do not hold power date to take up the law as their own, they must be stopped.

Through struggle, and the ‘revolutionary micropolitics’ it comprises, people will build the new framework needed for true justice.

Thailand’s protests, led by youth and students, seem to be only intensifying. With no viable political mechanisms in place to either manufacture consent or allow democracy to function as a ‘figleaf for oligarchy’, it seems that only brute force and suppression is left as a tool for the government. Photo Credit: Prachatai

Thailand’s protests, led by youth and students, seem to be only intensifying. With no viable political mechanisms in place to either manufacture consent or allow democracy to function as a ‘figleaf for oligarchy’, it seems that only brute force and suppression is left as a tool for the government. Photo Credit: Prachatai

Asia Art Tours: With Thailand’s history of Sakdina, the stark divide between rural or urban, and a powerful monarchy is there any sense that true justice is possible within the present framework of the country?

Tyrell Haberkorn: The short answer is no. The longer answer is that the struggle for justice is one that can only take place over a long period of time. Through struggle, and the ‘revolutionary micropolitics’ it comprises, people will build the new framework needed for true justice.

Asia Art Tours: And if US abolitionists demand the abolition of structures like policing or prisons for justice, what transformations must Thailand undergo in order to meet the demands so many protesters (past and present) have made for justice?

Tyrell Haberkorn: This is a great question – and makes me want to re-read Mariame Kaba’s recent book with Thailand in mind. Within Thailand, two institutions which need to be transformed are the prisons and the courts. Over the past fifteen years, I have spent a lot of time in the courts observing freedom of expression and other human rights and political cases. With a few exceptions, the overwhelming disinterest of the courts in rights, and in the people, is palpable. With respect to the prisons, Thailand has one of the highest incarceration rates in the world, with many of those imprisoned locked up for nonviolent drug crimes. Transforming the courts and the prisons would be a start!

Protesters covering Bangkok’s Democracy Monument with an LGBTQ flag in solidarity with the larger democracy movement in Thailand. Photo Credit: Prachatai

Protesters covering Bangkok’s Democracy Monument with an LGBTQ flag in solidarity with the larger democracy movement in Thailand. Photo Credit: Prachatai

To conclude, below please find our brief interview w. Professor Emeritus Thongchai Winichakul on the ‘Hyper-Royalism’ of Thailand’s powerful monarchy.

Asia Art Tours: You’ve discussed how images are crucial for understanding Thailand. To begin with the images of October 6th, 1976, how do these past images of state violence influence the political dreams and visions we see in Thailand today, both for protesters who critique and supporters who ally themselves with Thailand’s Monarchy?

Thongchai Winichakul: The Oct 6 images have stunned people of later generations, thus leading them to questioning how such an atrocity could happen. The questioning has led many to become disillusioned from the state’s dominant royalism. The current protest movement has expressed several times that the Oct 6 massacre was part of their awakening. For the royalists, in recent decades they have been quiet about the Oct 6 massacre. Occasionally they use the images or allusions to the images as intimidation to the critics of the monarchy.

Art exhibit at Thammasat University, showing images from the October 6th massacre. For articles featuring/discussing these graphic and disturbing images see here or here. Image: CC 4.0

Art exhibit at Thammasat University, showing images from the October 6th massacre. For articles featuring/discussing these graphic and disturbing images see here or here. Image: CC 4.0

Asia Art Tours: In Thailand’s Hyper-Royalism: Its Past Success And Present Predicament you discuss spectacle, even citing Guy Debord to explain how the monarchy dominates the Thai imagination:

Guy Debord asserted that “the spectacle is the main production of present-day society… the spectacle is not a collection of images, but a social relation among people mediated by images” (1983, pp. 14, 15). . . Thailand is an imagined community under the sacred monarchy mediated and constructed by visual effects.

Could you discuss how (during the last years of King Bhumipol until now with King Vajiralongkorn) you’ve seen the ‘spectacle’ of hyper-royalism evolve in Thailand? And what role do you see social media playing in intensifying or accelerating this ‘spectacle’?

Thongchai Winichakul: The visual effects that had produced hyper-royalism was mostly in the era of TV and prints. Now the dominant mode of visual representations is social media, not TV and prints. They are fundamentally different at least in three respects: 1) one-way traffic of information vs multiple-way traffic and easy reproduction; 2) the state’s ability to control and manipulate the visual-knowledge effects vs the lack of such ability; 3) public participation in the production and the critiques of visual representation in the social media mode. These issues deserve much more examination, more than I can do.

Politics (= power relations) in Thailand is not only about political economy but also about moral authority. Oftentimes the latter became more important than the former.

Images of the king dominate the visual landscape and mental geography of Thailand. These images and the idea of the royal family as godlike are increasingly contested by protesters in Thailand. Image: CC 4.0

Images of the king dominate the visual landscape and mental geography of Thailand. These images and the idea of the royal family as godlike are increasingly contested by protesters in Thailand. Image: CC 4.0

Asia Art Tours: In your writing, I was struck by how often ‘good and evil’ are frameworks in Thai Political discourse:

“To the Thai public, thanks to Cold War propaganda, the communists were not opponents of capitalism, but the evil enemy who wanted to destroy Thailand by abolishing the monarchy and everything that was Thai. The fight against these communist threats was the beginning of hyper-royalism”

Could you explain how Thailand’s royals and capitalist allies managed to convince the Thai public that communism was ‘evil’, and that the royals/capitalists were ‘good’ by critiquing ‘virtue’ rather than political economy?

Thongchai Winichakul: Because politics (= power relations) in Thailand is not only about political economy but also about moral authority. Oftentimes the latter became more important than the former.

For more on these two scholars simply search their names, they have been published extensively.