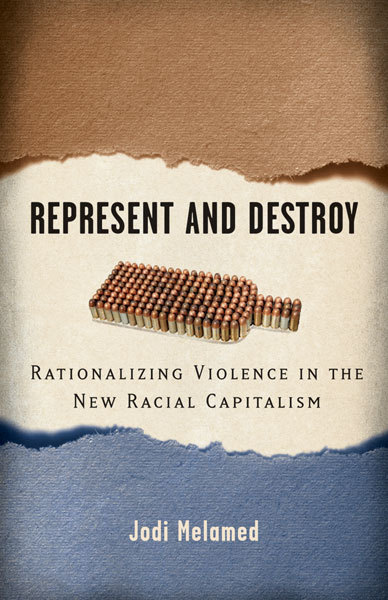

To understand the links between Capitalism and White Supremacy, I interviewed the brilliant, angry & abolitionist voice of Dr. Jodi Melamed. Jodi is an associate professor of English and Africana Studies at Marquette University and author of my favorite book on Racial Capitalism & Universities: Represent and Destroy.

For those who are new to Dr. Melamed’s Work, here is what Ruth Wilson Gilmore had to say : “A brilliant correction to both Weber and Winant, Represent and Destroy demonstrates how ‘the control over the means of rationality’ characterizes post-World War II US liberal racial orders. Working against the grain of change-as-progress, Jodi Melamed painstakingly demonstrates how official anti-racism has steadied, rather than dissolved, race as a structuring force of capitalism.”

This is part 1 of our interview, You can read part 2 of our conversation here!

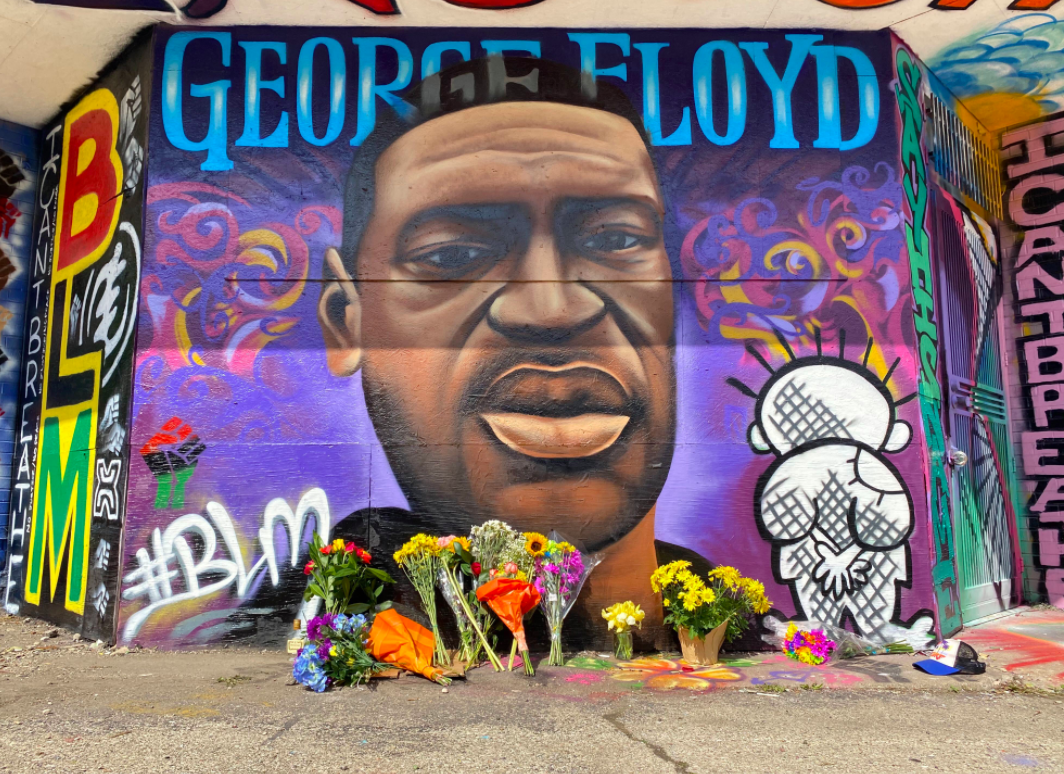

Asia Art Tours: Much of our correspondence has been on the limits (and at times deliberate obfuscation and cooptation) that occurs within University systems to deescalate the liberatory potential of radical movements. The abolition movement that has emerged in the wake of the State Murder of George Floyd has had both the praxis of direct action (burning of police stations, taking of autonomous zones) and cited the theory of academics who have worked within abolition for long periods, commenting on this moment. For you what praxis has most excited you about this current moment and why?

Jodi Melamed:I am truly excited about the emergence of Black self-defense, community defense, and the armed and unarmed defense of activists, marchers, and protestors as a central praxis of direct action in the current conjuncture. To me, this means that this movement (of movements) is wide-eyed about the fact that white individuals and law enforcement use physical violence as a tool to enforce the economic and political subordination of African Americans, Indigenous people, Latinxs, and queer and trans people of color.

Among all the horrors captured in Darnella Frazier’s video of the police lynching of George Floyd was the fact that police maintain their impunity to do violence work in lower income communities of color by criminalizing the acts through which people try to defend themselves and others against brutal, punitive, and often illegal police actions. So “trying to save your life and others’ from the police” is one of those things that white supremacy criminalizes doing “while black.”

Police routinely use charges of resisting, delaying, or obstructing a law enforcement officer to criminalize people for the totally understandable actions they take to defend themselves from the consequences of police encounters, from running away, to refusing to talk to an officer, to demanding proof that an officer has reasonable suspicion to interfere with them. George Floyd tried to save his life from officers he knew would use force to put him into a police car by stating directly that he was not resisting arrest, that he had claustrophobia and anxiety, and he lay down on the ground to show he was being completely nonviolent. Frazier’s video captures how traumatized, scared, and brave, she and other witnesses were, as they begged, pleaded, and screamed with Chauvin and the other officers suffocating Floyd. These witnesses clearly wanted to save George Floyd’s life, but there was no way for them to do so without risking dying themselves at the hands of these officers who so clearly did not value Black lives.

As Charles Kautzer reminds us in his essay, “A Political Philosophy of Self-Defense,” “communities of color defend themselves as much against a culture of white supremacy as they do against bodily harm.” In the era of state abandonment of communities of color to COVID 19, on top of decades of racial capitalist neoliberal austerity, it is clear that communities of color also defend themselves against what Ruth Wilson Gilmore calls “the anti-state,” that is, governance organized around killing abandonment and organized asset-stripping. Always insurrectionary, the self-defense of communities of color becomes revolutionary when enacting safety means turning away from the state to do safety and protection otherwise.

Now, during marches, the first priority of the movement is often stated as keeping protestors safe. In the face of white supremacists shooting into crowds and killing people with their cars, and militarized law enforcement violence that includes the routine use of rubber bullets and breathe-robbing tear gas, marchers are actively defending themselves against predictable harms. They decide when and how to block off streets for actions, using cars ahead, behind, and next to marchers to protect them at all times. Trusted people known to organizers of marches, mostly young Black men and women, open-carry long rifles and hand-guns. And the predictable counter-insurgents tactics of the police – to criminalize community activists and get them off the streets – is not working.

Now, during marches, the first priority of the movement is often stated as keeping protestors safe. In the face of white supremacists shooting into crowds and killing people with their cars, and militarized law enforcement violence that includes the routine use of rubber bullets and breathe-robbing tear gas, marchers are actively defending themselves against predictable harms. They decide when and how to block off streets for actions, using cars ahead, behind, and next to marchers to protect them at all times. Trusted people known to organizers of marches, mostly young Black men and women, open-carry long rifles and hand-guns. And the predictable counter-insurgents tactics of the police – to criminalize community activists and get them off the streets – is not working.

In Milwaukee, Wisconsin, where I live, the arrest of two community defenders led to the spontaneous and joyful coming together of an organic defense committee on the street in front of the jail. People came and vowed to stay until the activists were released. They turned the space into a picnic grounds by day, with a bounce house and video games for the kids, and an out-door club at night, complete with a soundstage. So the arrests – police repression in the name of public safety – completely backfired; people found their sense of safety, joy, and pleasure in protesting the police.

AAT: What theories have you turned to in understanding or thinking through this moment?

AAT: What theories have you turned to in understanding or thinking through this moment?

JM: First and foremost abolitionist critique. And for the reason that it lets us – at this moment – think absolutely pragmatically about undoing white supremacy by fighting against the white supremacist law and order that is necessary to maintain our contemporary neoliberal racial capitalist social order of organized abandonment, where so many people don’t have the basics they need to be safe – in terms of secure housing, secure employment, and secure healthcare.

In fact, at this moment, with the Trump regime sending camouflage-wearing border patrol agents into Portland, calling protestor “violent anarchists,” detaining people on the streets without warrants, using a brutality honed against immigrants on the southern border to target multiracial protestors, including white people (some of whom are experiencing state violence targeting their bodies for the first time), I have become convinced that abolition work to undo the organized violence of white supremacist law and order is actually the best defense we have against rising authoritarianism in the U.S. The question is whether white people here will liberate themselves from their limited concept of safety and recognize as Miriame Kaba says that “a safe world is not one in which the police keep black and other marginalized people in check through threats of arrest, incarceration, violence and death.”

For me, Ruth Wilson Gilmore is the abolitionist thinker of the moment for two reasons. First, her work provides the racial capitalist framework that lets us see that police and prisons in the U.S. are not so much about the small profits of private prisons or prison labor or selling criminal justice technologies, as they are about the big, structural need of economies of abandonment and elite deal-making for ‘human sacrifice’. That is, as Ruthie puts it, “criminalization remains a complicated means and process to achieve a simple thing: to enclose people in situations where they are expected, and in many ways compelled, to sicken and to die.” So deliberately propagated fatalities as an infrastructural requirement of accumulation through financialized, extractive, logistical capitalist assemblages, whose profits depend on being unencumbered by the need to consider the well-being of humans or the planet.

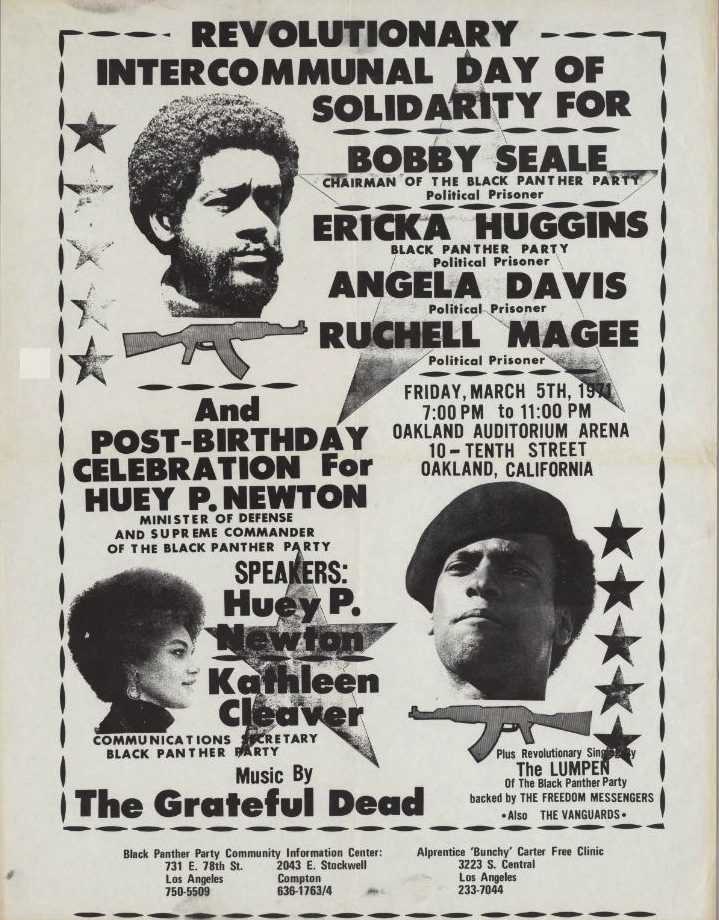

(Image courtesy of the Online Archive of California, UCLA Special Collections)

Second, Gilmore’s grounding in the Black Radical Tradition, in all is historical and global stretch, means she connects all the dots, so that the idea of abolition as “changing everything” (the title of her new book) feels eminently possible. She helps us see that abolition has always been going on and is happening around us in exciting ways right now. It is as old as maroonage and stealing away under slavery; as old as the post-civil war abolition democracy, where formerly enslaved people walled down the path of self-determination until the counter-revolution of property ended the first reconstruction. And she lets us see that the contemporary calls to defund the police and re-distribute resources so that communities are equipped to provide their own safety and well-being did not come out of nowhere.

They were already present in the decades long fight against the prison industrial complex; in the feminist queer intersectional visions of the early #blacklivesmatter movement; in the kinds of questions the Standing Rock movement helped us ask about relations to indigenous communities, non-human forms of life, and the alive planet. Indeed, as Ruthie says, abolition has to be “green” – to take seriously issues of environmental harm – for which it has to be “red” – to think about the redistribution of resources needed for the well-being of the most vulnerable – and that to be “green” and “red,” abolition has to be international.

So there is a great double move in Gilmore’s work between an incisive analysis of oppression and pragmatic rehearsals for freedom. For me, this is summed up by juxtaposing her seminal definition of racism – “racism is the state-sanctioned and/or extra-legal production and exploitation of group-differentiated vulnerabilities to premature death” – with her one-line mantra designed to build abolitionist political imaginations – “where life is precious, life is precious.” So ‘premature death’ is the key indicator of the kind of worlding achieved by the infrastructures necessary for racial capitalist accumulation. But as Ruthie shows us, all the time people are also putting together social capacity, resources, land, and consciousness to do worldings that regard life as precious and put in place policies and practices to protect it.

AAT: and lastly what would you council academics or PhDs against, in this potentially revolutionary moment? Where is the movement outracing theory, and where might an academic’s role to ‘explain or theorize’ be counter-productive in this moment of history?

JM: In U.S. protests against police killings, an acronym has emerged to state with boldness that cops who appear to reformists as “bad apples” for using excessive force are actually doing exactly what they are hired to do and reveal the true, systemic violence of policing as a punitive institution. That acronym is A.C.A.B. All Cops are Bastards. Although I am sorry to reinforce the stigmatizing, misogynist, and heteronormative logic encoded in the term “bastard,” I would like to propose an acronym for the U.S. university system that is equally bold: A.A.A.B. All Administrators are Bastards.

Across the board, University administrators are responding to this potentially revolutionary moment in a completely opportunistic, counter-insurgent, and corporate manner. First, in line with the performative role of “diversity” initiatives, universities are occupying themselves with all manner of meaningless performatives: statements in support of Black students; lip service to a pathologizing “trauma” discourse; maybe, at best, some town halls or webinars, usually featuring administrators themselves, who have no expertise in U.S. racial history, race and ethnic studies, or anything that could provide useful context in the moment. So I would council anyone in academia to avoid giving energy to all the white performatives of the moment.

Across the board, University administrators are responding to this potentially revolutionary moment in a completely opportunistic, counter-insurgent, and corporate manner. First, in line with the performative role of “diversity” initiatives, universities are occupying themselves with all manner of meaningless performatives: statements in support of Black students; lip service to a pathologizing “trauma” discourse; maybe, at best, some town halls or webinars, usually featuring administrators themselves, who have no expertise in U.S. racial history, race and ethnic studies, or anything that could provide useful context in the moment. So I would council anyone in academia to avoid giving energy to all the white performatives of the moment.

Along with the white performatives, many universities are actually giving their private police forces more funding, tools, and roles to play on campus, from policing mask policies to purchasing body cameras that increase campus police surveillance and coordination capabilities. At the same time, campuses are passing anti-demonstration policies that seek to suppress protests, marches, and democratic energies from being present on college campuses. At my university, they are telling faculty to call the university police force if students refuse to wear masks, expanding the role of policing on campus. There are exceptions where organized faculty, staff, and students working together are diminishing policing on campus and surrounding neighborhoods, such as at the University of Minnesota and the University of Washington, Seattle.

What does the radical consciousness of the times tell us about the university as a place of conflict, a power base for competing tendencies, for and against today’s eruptive social movements? The ancestors and thinkers being thrown up by the movement are, to a large degree, women of color activists who have not been institutionalized in university curricula, but whose thinking enlivens campuses in the “undercommons” spaces of LGBTQ resource centers, gender and sexuality studies programs, critical race theory courses, and Black student council study groups. I’m talking the beautiful troublemakers, including Assata Shakur, June Jordan, Angela Davis, Audre Lorde, and so many more, who tell us – often on facebook pages or at student-organized talks – that (to quote Shakur) “No one is going to give you the education you need to overthrow them.” And yet, universities are hotbeds of abolitionist critique and knowledge production. Perhaps all of this is just to say, organizing and struggle cross universities, as they do other institutional spaces, in complex ways.

But, to answer your question about what might be counter-productive about academic “fixing” of this moment for analysis, is that the disciplines (political science, sociology, you name it) are all still completely trapped within liberal divisions of knowledge which are colonial and white supremacist divisions of knowledge. For these disciplines, the political real is always circumscribed by liberal thought.

And at this moment, eruptive movements are helping us think and feel our way to a political real that knows the tricks of liberalism as not only political and economic philosophy, but also a theory and practice of racial colonial management, whose core concepts – property, deed, citizenship, progress, individualism, freedom – all have racial genealogies. University knowledge production might truncate what we are learning from resistance movements about how to think and do politics beyond liberal modes of political knowledge, that is, how other categories of relationship and immediacy – kinship, survival, welcome, relationality, mutual aid – anchor better political reals.

No pressure, Matt, but I think there is a huge need for non-university based intellectuals to think with social movements, because they (you) are not under the same kind of pressure (or temptation) to make their thinking legible for the liberal modes of knowledge that dominate universities.

For more w. Dr. Melamed please check out the conclusion of our interview here. You can find Jod’s Book, Represent and Destroy here. We also recommend her writing in the Boston Review.