To understand the links between Capitalism and White Supremacy, I interviewed the brilliant abolitionist voice of Dr. Jodi Melamed of Marquette University. Jodi wrote my favorite book on Racial Capitalism & Revolution: Represent and Destroy. This is the conclusion of our interview; you can find part 1 here.

Asia Art Tours: Your work Represent and Destroy highlights the explicit ways that outside forces (the State, Capital) have shaped what is acceptable multiculturalism (building individual icons/cultural forms who represent singular identities, and using this to guide subjects towards the managerial systems of Capital and the State). Could you explain how this works within the University Level?

Jodi Melamed: Since the 1990s, the U.S. university has successfully welded its traditional mission of individual self-development (sometimes couched as an “education for citizenship” or “making global citizens”) to a newer role of disseminating an acceptable multiculturalism that limits knowledge about race, racism, and anti-racism to the same liberal political and philosophical framework that posits possessive individualism, property, and exclusive citizenship as universal truths that all civilized and good human societies uphold.

This is really counterinsurgent because it takes the desire of white Americans to be good anti-racists and sutures it to an understanding of anti-racism that not only is mostly cultural and symbolic – a multicultural literary canon, a multiracial professional-managerial class – but one that actually represents capitalism and the material racial inequality it requires as foundational for anti-racism. It represents the meaning of anti-racism as merely individualism for everyone, equal opportunity to compete in the open marketplace regardless of skin color, and abstract equality under law, the practical outcomes can continue to reflect racialized asymmetries of wealth and political power.

So while Black freedom struggles, Indigenous sovereignty movements, the lifeworlds of Latinx migrants, and communities of color are so rich with knowledges, teachings, writers, and intellectuals that show how the struggle against racial oppression is always also a struggle against economic oppression, acceptable multiculturalisms in U.S. universities marginalize that lesson and misrepresent “racial progress” as the presence of Black, Indigenous, and People of Color individuals in positions at the top of the U.S. hierarchy.

And as you mention, multiculturalism treats human experience and vectors of oppression anchored in stigmatized identities as distinct and serial rather than intersectional and heterogenous, so that the way the dividing line is really drawn between the valued and devalued remains mysterious. That is, it is only seen partially and from the point of view of liberalism’s obfuscating generalities (“individuals,” “citizens,” “women,” “African Americans.”)

So universities are not teaching white supremacy, but they are teaching multiculturalism in a way that provides the same kind of miseducation and not knowing what you don’t know. That is, multiculturalism, like white supremacy, continues to provide the “white misunderstandings, misrepresentations, evasion, and self-deception on matters related to race” that Charles Mills tells us are “psychically required for conquest, colonization, and enslavement,” as well as mass incarceration, segregation, and economic abandonment.

AAT: The other portion of Represent and Destroy that I see as incredibly relevant is your work into how the university and capitalist institutions seek to police or expel what I call unacceptable multiculturalisms , that is literature, dialogue or frameworks that build intersectional identities, anti-racisms and other solidarities that challenge Capital or state.

AAT: The other portion of Represent and Destroy that I see as incredibly relevant is your work into how the university and capitalist institutions seek to police or expel what I call unacceptable multiculturalisms , that is literature, dialogue or frameworks that build intersectional identities, anti-racisms and other solidarities that challenge Capital or state.

To put your work in dialogue with the Dr. King quote that defines our present: “A riot is the language of the unheard”. What are the ‘unacceptable multiculturalisms’ that the university or capitalist systems seek to block in order to prevent certain frameworks, dialogues, or solidarities from existing?

JM: The good news is they can’t block them! It’s like “a riot is the language of the unheard.” The riot is still speech. It’s still political action, even if the state, capital, and administrative classes in universities refuse to “hear” it as such. The university will try to performatively endorse “Black Lives Matter” merely as a slogan, while decrying abolitionist demands to defund the police as irrational, radical, or childish.

They will also try to foment conflicts over resources and recognition by focusing on a few demands from activist Black students and redistributing resources away from undocumented students or LGBTQ POC students. But the truth is, the university only allots peanuts to these students and the programs that support them, and activists students are not going to fight over peanuts and crumbs.

In terms of “unacceptable multiculturalisms” (a great term), unruly dialogues, frameworks, and solidarities are enlivening and interconnecting and expanding in truly exciting ways. This is a revolutionary moment because everyone is breaking down the partitions that separated “the political” into silos and “interests.” The other side of the general bankruptcy of liberalism revealed as dependent on white supremacist law and order to protect property and the right of capitalists to destroy the planet is the knitting together of infrastructures of survival into a whole other circulation of sociality that is international, red (indigenous and redistributive), green (savvy to environmental harm), Black, brown, anti-capitalist, and places its care and revolutionary hopes in the most marginalized.

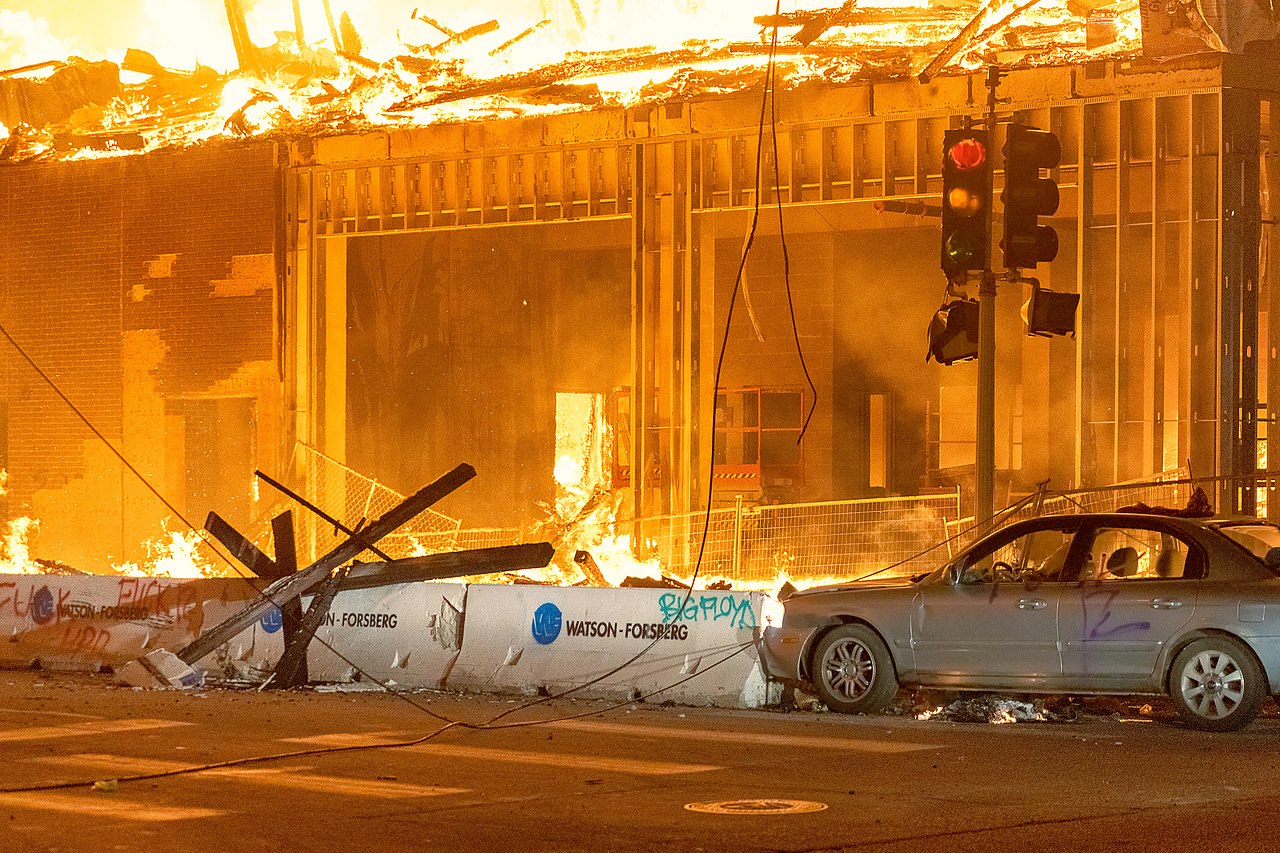

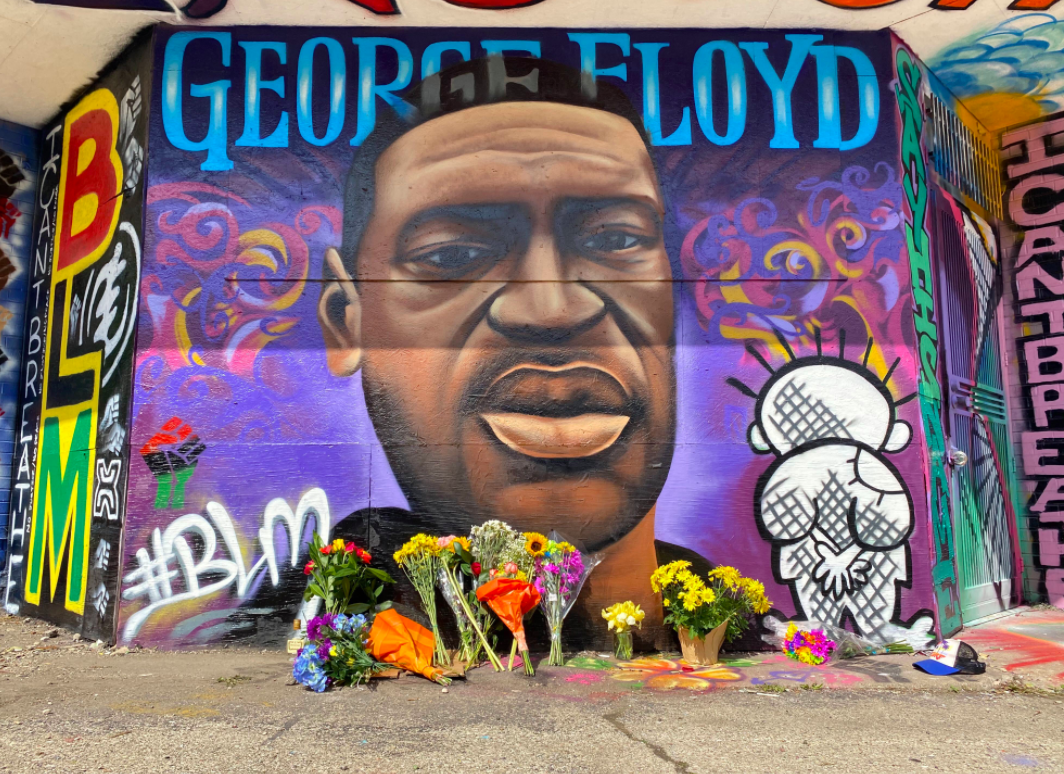

In my city, the Palestinian “Handala” – a scruffy cartoon character who represents dogged resistance – is on the mural commemorating George Floyd. Black lives matter marches are lead from the front by people in wheelchairs. Unhoused community members are in charge of security, food, and water. Black womyn and queer and trans activists of color set the agendas and provide the analysis. Maybe because of Covid-19 and what its reminded us about survival and interdependency, there is a commitment to leave no one out, to make sure everyone is protected on their own terms.

AAT: If ‘unacceptable’ multiculturalisms are able to grow… what may be some of the radical changes or new understandings that this movement brings into being? This has been a year for global protests and uprisings: Lebanon, Chile, West Papua, Palestine, Hong Kong, Thailand, Haiti, France, Algeria, Syria and many others come to mind. For you, what are the truly revolutionary threads that we should continue following and tying together?

JM: Here is how I think about it: It has become abidingly clear that the neoliberal infrastructures that capitalist elites maintain to keep the circulations going out of which their profits emerge – supply chains, property laws, borders, policing, complex structured financial products, dark money pools – require ethno-nationalist or racial authoritarianisms and threaten human well-being on a planetary level.

Yet this is not the whole story. Since the beginning of racial capitalist colonial modernity – and definitely over the last 40 years of organized neoliberal abandonment – there have always been other infrastructures of survival that “get things done” otherwise, that arrange circulations of meaning, matter, and social capacity for collective survival, or for the survival of collectives, rather than for profit. Even before Covid 19, the resistance movements and street protests you mentioned going on all around the world – from Hong Kong to Palestine to Oakland – were already refusing the unlivabilities being inflicted on the ordinary people by extractive, financialized and authoritarian neoliberal crony capitalists.

Since COVID 19, many of these infrastructures of survival have enlivened and sometimes feel like infrastructures of revolutionary change; they provide us with alternative political reals – existing, influential political reals – that depart from racial capitalist sanctities like property above people and citizenship as a tool for partitioning workers and hoarding or hiding capital.

For example, indigenous resistance movements often start from the insight that relations between people and their homelands have not been broken, that is, they refuse what Aileen Moreton Robinson calls “the white possessive”: the process through which the materiality of significations, such as buildings or deeds, are perceived as evidence of ownership by those who have taken possession.

For example, indigenous resistance movements often start from the insight that relations between people and their homelands have not been broken, that is, they refuse what Aileen Moreton Robinson calls “the white possessive”: the process through which the materiality of significations, such as buildings or deeds, are perceived as evidence of ownership by those who have taken possession.

For indigenous nations tribes ,and bands, inclusion or equality within the nation-state system was always a strategy of erasure or genocide to be fought against. Because of this, there is a clear-sightedness in indigenous struggle about the violence of nation-state citizenship and the capitalism it provides the framework for. (As Glen Coulthard puts it in one essay title, “For Our Nations to Live, Capitalism Must Die.”)

Even as Brazil and other governments are weaponizing a non-response to COVID to kill Native people ,in the U.S., the Supreme Court just provided recognition of treaty rights and never-extinguished Indigenous jurisdiction in McGirt v. Oklahoma, which can be seen as another link in the infrastructure of indigenous resistance and survival; it is an after-effect of the continuous operation of indigenous governing structures and life-ways. It will indigenize place-making in much of Eastern Oklahoma and maybe diminish settler colonial circulations, maybe just a little bit, but in a meaningful way.

What is exciting is that all these revolutionary threads – indigenous resistance, abolition, the decentralized activity of hundreds of thousands of migrants crossing borders, insisting on the right to move for survival and well-being – are resolute about capitalism as violence to collective existence and seek other forms of relationality, exchange, and metabolism between human groups, non-human forms of life, and the earth.

What is exciting is that all these revolutionary threads – indigenous resistance, abolition, the decentralized activity of hundreds of thousands of migrants crossing borders, insisting on the right to move for survival and well-being – are resolute about capitalism as violence to collective existence and seek other forms of relationality, exchange, and metabolism between human groups, non-human forms of life, and the earth.

For many people already living in the post-apocalypse – Indigenous nations, war survivors, genocide survivors, the detained and incarcerated, the uprooted and disowned – it is not impossible to imagine the end of capitalism.

AAT: You’re a keen observer on the mechanisms of liberal recooperation of radical movements. That is to say, making radical movements capitulate to the structures of the state, capitalism and hierarchy. For this current moment, many individuals are appointing themselves leaders, as a way to lead us back to these recursive and ultimately tyrannical structures upon which the USA is based.

JM: As we’ve talked about, your question about cooptation and defusing radical movements hinges on property and the capacity of both the right-wing and white and non-white liberals in the U.S. to criminalize political action that takes the form of 1) violence against property during uprisings (“looting”) or 2) violence against capitalism more generally (boycotts, general strikes).

But first, can we talk about how unsurprising and amazing it is that corporate capitalist humanism has fully embraced the slogan “Black Lives Matter” as an opportunity for commodification, market niche making, and white-washing corporate violence? Nike led the way with the Colin Kaepernick commercials. University-corporations (that is, all universities) led the way too with the instant, meaningless “rebranding” of their missions as down with “Black Lives Matter” misconceived as more robust “diversity”. But across the board, from Microsoft to Chevron to McDonald’s to Amazon, the biggest corporate supporters of criminal justice technologies, the biggest harmers of the environment, the biggest exploiters of black and brown labor, have embraced an obfuscatingly humanist representation of “Black Lives Matter” that is the nothing more than the new “All Lives Matter.”

But first, can we talk about how unsurprising and amazing it is that corporate capitalist humanism has fully embraced the slogan “Black Lives Matter” as an opportunity for commodification, market niche making, and white-washing corporate violence? Nike led the way with the Colin Kaepernick commercials. University-corporations (that is, all universities) led the way too with the instant, meaningless “rebranding” of their missions as down with “Black Lives Matter” misconceived as more robust “diversity”. But across the board, from Microsoft to Chevron to McDonald’s to Amazon, the biggest corporate supporters of criminal justice technologies, the biggest harmers of the environment, the biggest exploiters of black and brown labor, have embraced an obfuscatingly humanist representation of “Black Lives Matter” that is the nothing more than the new “All Lives Matter.”

This is important because it is good-old neoliberal multicultural ideological brain-washing yet again trying to make it seem as if robust anti-racism is compatible with neoliberal capitalisms and their modes of accumulation, which require racialized strategies of devaluation and disempowerment. In other words, “Black Lives Matter” has been co-opted by corporations and investors (and the municipalities that court them) to try to deny and disavow that racial oppression is always already economic oppression, is always already capitalist violence.

Remember Marx’s famous critique of the “so-called original accumulation”? About how political economists tell fairy tales above wealth having been earned through “right” and “hard work,” but “[in] actual history, it is a well-known fact that conquest, enslavement, robbery, murder, in short force, play the greatest part”? Well, this recursive process – of making force appear as “right” – never stops and is part of how capitalism functions. It white-washes the force capitalism requires (land grabs, asset-stripping, extraction, racial arbitrage to fix markets) by using liberal categories of legality (“property,” “eminent domain,” “responsibility to shareholders”), using racism and liberal anti-racism (so the fault is always in the “unimproved” people and their failings, not policy and practices), and using policing as a means to criminalize and repress people who have been made asset-less, to criminalize them in advance for being potentially against property and capital.

At every moment, when the conversation turns to “violence,” we have to turn it around like Marx does, to show that all the violence actually emanates from white supremacist capitalist oppression, from the policing, from property itself as a congealment of theft, murder, extraction from human lives.

This is especially important right now, as the Trump regime and the right wing are creating spectacles and using strategies from the white supremacist law and order playbook to enliven the authoritarianism they seek to put an end to electoral democracy in the United States, if Trump cannot win re-election through the electoral process.

White liberals, all liberals – when they condemn political violence and echo the law and order discourse in even reformist ways – are fueling Trump’s authoritarian fire. There is no law and order under the current “facts” of our national existence that is not part of the structure of white supremacist law and order. So anyone who wants to offer “dialogue” or “nonviolence” under the umbrella of law and order is completely culpable and counterinsurgent. But of course, there are lots of ways to talk about undoing harm through abolitionist frameworks. To talk about safety through solidarity. To talk about a society that is not violent.

In the U.S., we need to have a way to discern normalization with white supremacist law and order and to distinguish it from abolitionist frameworks of reducing the conditions under which people resort to violence. We need something like that the critique of “normalization” and the “co-resistance” standard that is so useful in the context of Israel/Palestine, for Palestinian liberation and solidarity movements.

AAT: Lastly, this is a tough question, but I can’t think of anyone better to ask. Something that is a quandary for me about movements that ask us to decolonize, is that it (seemingly) implies the land has owners. Similarly with reparations, the mechanism seems to be from within the exploitative framework of capitalism. Therefore, if land can be stolen, it is not a commons or some other anarchist framework, but one that we should view through the laws and lens of capital and property. That if wages can be returned, we should continue to view abolition through a capitalist worldview.

JM: Thank you for asking this question! It helps me explain what I mean by having to think politics outside liberal modes of political knowledge. It’s also about the “white possessive” I mention above; in particular, it’s about not accepting the evidence of those who have taken possession as the last word, not accepting that liberalism and capitalism are the totalities they want us to think they are, because they are not!

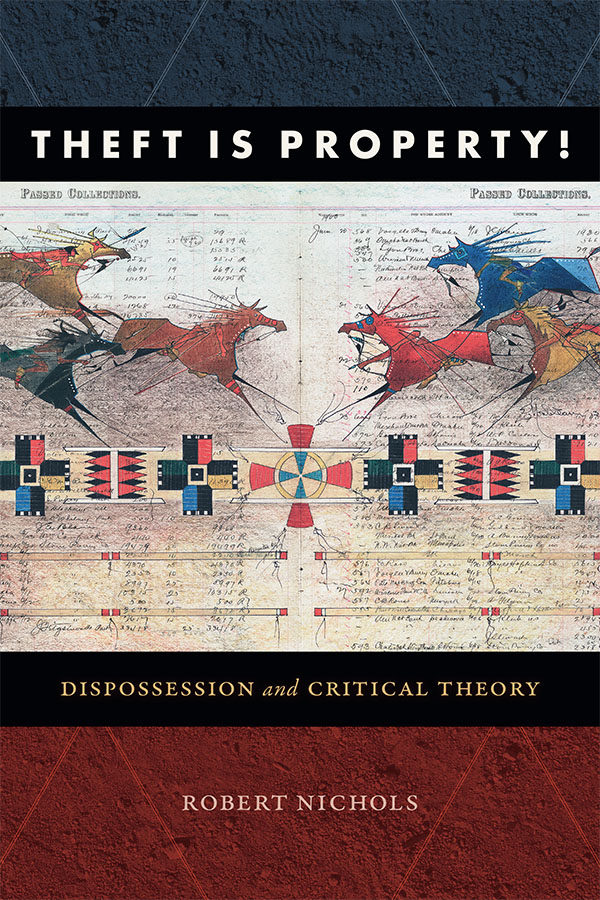

The best person to ask about this, actually, is probably Robert Nichols, who just wrote a brilliant book called Theft is Property!. Building off the insights of indigenous resistance movements, thinkers, and theorists, he describes indigenous dispossession as a recursive process along the lines of how I read Marx on primitive accumulation: Settler societies bestow property rights recursively on Native communities after land theft to legitimate indigenous dispossession.

The best person to ask about this, actually, is probably Robert Nichols, who just wrote a brilliant book called Theft is Property!. Building off the insights of indigenous resistance movements, thinkers, and theorists, he describes indigenous dispossession as a recursive process along the lines of how I read Marx on primitive accumulation: Settler societies bestow property rights recursively on Native communities after land theft to legitimate indigenous dispossession.

It helps us think capitalism as a species of theft that works 1) by forcibly incorporating non-capitalist forms of life (including land as a non-human relative into capitalist relations in a way that 2) requires its divestment and alienation from those who are recursively posited as its “original owners.” (Patrick Wolfe summarizes this in a way that lets us see how the category of “property” disguises the force that is the real source of capitalist wealth. He writes, given the realities of conquest, “the American right to buy always superseded the Indian right not to sell.”)

But here is the thing. Just because capitalism comes in and formats everything for its mode of relations and exchange (and enforces that form of appearance at the point of the sword, the barrel of the gun, the threat of imprisonment), that doesn’t mean everything has been subsumed and become nothing more than what capitalism says it is, once and for all. Other systems of circulation – for example, indigenous circulations of meaning, matter, sociality – continue. Capitalism just creates a dominant form of appearance that makes you believe its logics are the only real and operable ones. But it is not true. Many kinds of circulations informed by very different modes of relationality overlap one another “in the same place,” without replacing one another, like currents in a stream, though they may weaken or enliven in opposition to one another.

I like to talk about the lesson I learned from friends who are part of the Menominee Nation. Their relations with their forest help me think about how capitalist circulations overlap with grounded indigenous circulations rooted in interconnectivity with agential non-humans. The trees on the reservation live out their own life cycles and are known as grandmothers and grandfathers. They are simultaneously central to Menominee tribal enterprises, which provide “stumpage” fees to tribal citizens , and are part of cycles of gifting and honoring obligations. For example, in 2016 the Menominee fulfilled diplomatic and kinship responsibilities by bringing trees to Standing Rock to become wood to keep people warm. Yet they also sell the same trees for lumber. The trees are simultaneously “property” and “ancestors,” depending on the relations at play.

So decolonization and abolition are about strengthening the relations, the circulations, already happening that are already NOT part of capitalist relations and circulations. As practices, decolonization and abolition expand, strengthen, interconnect, and circulate epistemes, relationships, ways of living, and interdependencies already defective for profit motives etc., and already nourishing structures of indigenous governance, community well-being etc. We just have to free our political imaginations from the capitalist worldview, which is part of what abolition and decolonization praxis helps us do!

For more w. Dr. Melamed please check out Part 1 of our conversation here. You can find Represent and Destroy here. We also recommend her writing in the Boston Review.