We were honored to speak with Journalist Ben Mauk on his award-winning article, ‘ Weather Reports: Voices from Xinjiang‘. For more of Ben’s outstanding journalism, visit: Ben-Mauk.com

Asia Art Tours: As an Armenian-American, I’ve been profoundly traumatized by the Xinjiang Genocide and globally the open reappearance of ‘camps’ and fascism. For you, how does the personal affect the political lens with which you wrote about Xinjiang? Can you tell us a bit about the man behind these honest, uncompromising pieces of journalism?

Ben Mauk: First off, I should say that I don’t know that I consider my personal background all that relevant. I always try in my work to find stories that aren’t being given enough attention, or stories that a government has suppressed, about places that are largely ignored by Americans and Europeans even though our histories and politics are always bloodily intertwined. In doing so, my interest is in the experiences of non-elite people: workers, farmers, teachers, children, the unemployed, prisoners, migrants. I hope to pass on their stories and priorities without overlaying my own prejudices or reportorial interests—without doing so consciously, at least. Of course, I have a background, and it contributes conscious and unconscious bias, and many blind spots, culturally determined and otherwise, but it’s part of the writer’s job to consider and work to address those. You do the work: a lot of research, talking to people from the area, talking to academics, talking to activists, asking locals how their stories are often misused or misconstrued by outsiders, asking what they would want a publication to focus on, and following their lead. That’s all you can do. If you abandon the project of writing outside your own experience, you have abandoned all journalism, and all but the most solipsistic literature and art—you’ve given up on communication itself.

China and Kazakhstan’s Border in Khorgas, Xinjiang. Photo Credit: Wikipedia

China and Kazakhstan’s Border in Khorgas, Xinjiang. Photo Credit: Wikipedia

With that objection out of the way, I’m originally from the United States, I’m Jewish, and I’ve lived in Germany for many years. I don’t think my writing requires or benefits from a “Jewish-American German immigrant” lens. On the one hand, yes, I was brought up to have a keen awareness of the tyranny of the majority and the banality of evil, partly as a result of being raised a Reconstructionist Jew, but you could equally say I’m the product of generations of defenders of organized labor or the child of liberal scientists or whatever.

All of these reasons and more—and not just a kind of reflexive “Never Again” attitude—are why the state-sanctioned oppression of minority groups are usually what I find to be most urgently deserving of attention. More selfishly, these subjects are interesting to me. How do states create and maintain “fugitives,” by which I mean communities who are definitionally illegal, and therefore deserving of extralegal treatment? How can these efforts be resisted? What would international solidarity with these communities look like? How are their plights misused by rival states to stoke conflict and war? These are the sorts of questions driving my work.

One thesis of mine—it’s part of the book I’m writing—is that the management of fugitives is how states test new methods of social control and surveillance before debuting them in the general population. This is as true in the United States as it is in China, although to different degrees and under different historical conditions. I think in both places we are seeing extractive capitalism in a fever pitch. Xinjiang is the world’s cotton bowl, it’s mineral rich and is a major regional exporter of oil and gas. Its development lies at the heart of several Belt and Road infrastructure projects. The situation has corollaries to the oil sands of Alberta and the displacement and mistreatment of First Nations people there, and with other extractive colonial projects across the North Atlantic region, in which you and I and everyone we know are implicated. That’s one place my interest comes from, and if you look over my body of work you’ll see that this is one connecting thread, from American uranium mining across the Navajo Nation, to the American and European history of bombing civilians, to the mass internment of minorities in Xinjiang.

Atajurt, co-founded by Serikzhan Bilash (right) was one of the most successful organizations in pressuring China to release Kazakh citizens and PRC-born Kazakhs who had been swept up in China’s Concentration Camps. He has since been coerced by Kazakhstan’s government to stop his organizing. Photo Credit: Youtube/Atajurt

Atajurt, co-founded by Serikzhan Bilash (right) was one of the most successful organizations in pressuring China to release Kazakh citizens and PRC-born Kazakhs who had been swept up in China’s Concentration Camps. He has since been coerced by Kazakhstan’s government to stop his organizing. Photo Credit: Youtube/Atajurt

Asia Art Tours: I was captivated by the formatting of ‘Weather Reports: Voices from Xinjiang’, letting Kazakhs speak for themselves rather than placing yourself as the narrator. What led you to write an oral history rather than a news article?

Ben Mauk: I was already becoming frustrated with the limitations and inequalities of the genre I operate in: conventional journalism, magazine writing. As I was reporting from Kazakhstan, it was increasingly clear to me that people from Xinjiang are the ones who should be telling their own stories, with as little interpellation or interpretation by an inexpert foreign journalist as possible. I saw my role as evolving from a journalist or writer—someone who contextualizes stories for a “Western audience,” whatever that is—into that of oral historian. An oral historian is not exactly a stenographer, of course. He produces and manages knowledge in certain ways, he is biased in his approach, but he also works to center firsthand experience in a more extreme way than journalists do.

A second, countervailing impulse was that I was already in Kazakhstan, and could safely do the work, unlike writers from China or Kazakhstan. Writing truthfully about the treatment of minorities in Xinjiang will get you imprisoned as a journalist in Kazakhstan, to say nothing of China, so despite the inequalities and unfairness of sort of parachuting in, outsiders are better-suited to safely and independently reporting on Xinjiang, a fact every journalist I know in Kazakhstan has pressed on me. So I felt I was in a structural position where I could write freely about this subject, but at the same time was in a position where I did not want to speak for people from Xinjiang, and did not want my work to be readily adaptable for any propaganda purposes, as dramatized narratives like this sometimes are (e.g. concerning defectors from North Korea). The idea for an oral history presented itself.

It’s hard to believe now, but when I first started looking into reports on camps and disappearances of relatives, in early 2018, Xinjiang was still one of those places that you heard almost nothing about in American or European news. There were a few reports about re-education camps, including an early CNN report, but it was not anything like a major news story. There was nothing firsthand from inside the camps themselves. Not like today.

Qaraqash No. 3 Training Center (墨玉县第三培训中心) A former vocational & technical education high school (职业技术高级中学), this facility was converted into a “correction through education center” (教育矫治中心) sometime between late 2017 and early 2018. Much of the razor fencing inside the compound appears to have been removed around mid-2019, however, suggesting that the purpose of the facility may have changed yet again. Source: Xinjiang Victims Database

Qaraqash No. 3 Training Center (墨玉县第三培训中心) A former vocational & technical education high school (职业技术高级中学), this facility was converted into a “correction through education center” (教育矫治中心) sometime between late 2017 and early 2018. Much of the razor fencing inside the compound appears to have been removed around mid-2019, however, suggesting that the purpose of the facility may have changed yet again. Source: Xinjiang Victims Database

I was in Kazakhstan in the summer of 2018 writing about the intersection of nomadic pastoralism and Chinese infrastructure investments for The New York Times Magazine. While doing interviews near the border with China, it was clear that a major, totalizing change was taking place in Xinjiang, one that affected the families of almost everyone I met, although at the time the details about the nature and scale of the internment drive were quite fuzzy, and people were scared to talk about it. The Chinese government still largely denied the existence of camps at this time. Only later did they claim that these were vocational schools, and there is still a lot of fuzziness in their description of internment, sliding between descriptions of “brain cleaning” and the deprogramming of extremists and terrorists on the one hand, and vocational instruction and poverty alleviation on the other. It’s quite inconsistent.

The more people I spoke with, the more vital it seemed to record and transmit their stories. It seemed to me an absolute emergency—people were leaving Xinjiang, speaking out once or twice, and disappearing or going quiet forever. Or they were desperate to tell their story and had no one to tell. It changed the course of my work for the next two years, up to the present day. What was happening there, the actual reality of it, was in danger of being lost, and this possibility offended every facet of my being: as a journalist, as a writer, as a leftist, as a Jew, as a human being. Luckily many people, including scholars from Xinjiang and those who have worked in the region for decades, people far more expert than I am, were similarly alarmed, and now there is a proliferation of material and evidence. I’ve taken four separate trips to Central Asia to record interviews there, and each time I’m a little better at it and a little more trusted in these communities. As a result, I’ve found avenues to people that are not available to someone who flies in only briefly, which of course is the position I was in on my first trip.

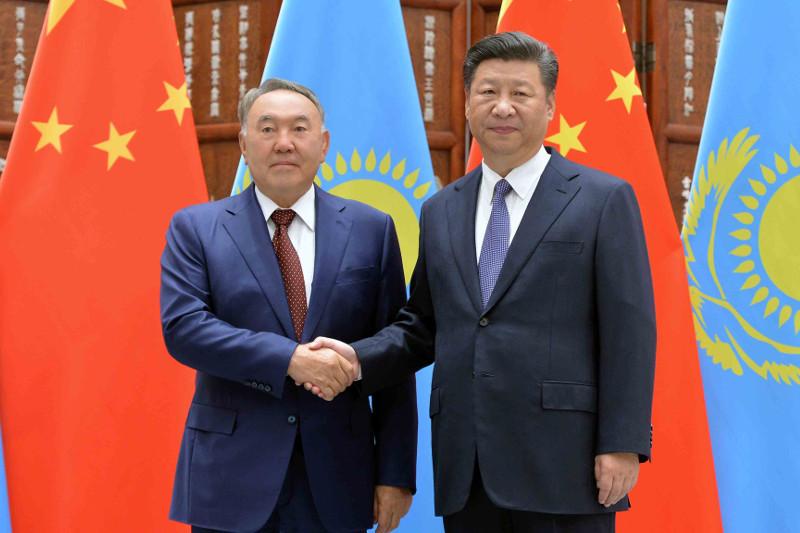

The former President of Kazakhstan Nursultan Nazarbayev and Xi Jinping. Nzarbayev resigned after months of heavy protests in 2019. Sadly, his replacement Kassym-Jomart Tokayev, has continued Nzarbayev’s unpopular policies, including Kazakhstan’s silence on Xinjiang and China’s Concentration Camps. Photo Credit: Inform.KZ

The former President of Kazakhstan Nursultan Nazarbayev and Xi Jinping. Nzarbayev resigned after months of heavy protests in 2019. Sadly, his replacement Kassym-Jomart Tokayev, has continued Nzarbayev’s unpopular policies, including Kazakhstan’s silence on Xinjiang and China’s Concentration Camps. Photo Credit: Inform.KZ

AAT: Considering media in a world of fascism, I think ‘objectivity’ without empathy are dangerous traits for a storyteller to possess. In an increasingly fascist world, how does objectivity, taking ‘both sides’ or platforming the authority figures behind these policies, as the AUTHORITY become dangerous or fail to help those facing genocide in Xinjiang or in other global crises?

BM: I reject the usefulness of the term ‘fascism’ in this question. I’m not sure what it actually means to call a 21st-century state fascist. Nor would I necessarily agree that the world is increasingly fascist. Certainly the average person is more aware of acts of authoritarianism and formalized brutality than they used to be. I don’t know that it then corresponds that there are more of these acts.

Instead, I would say that state power has expanded radically throughout most of the world, and the ability to exist outside of the state’s matrix of categorization and control has correspondingly decreased. Over the past fifty years we have seen zones of weak or no state sovereignty shrink to nothing, and the final enclosure by extractive state-affiliated industries of many hard-to-reach or marginal spaces that were once managed largely according to local or indigenous political traditions.

In Xinjiang, we have a special confluence of unchecked, quasi-totalitarian state authority, a huge investment of capital and manpower, and the experimental spread of technologies of biopower to surveil and assimilate a population: retina and face scans, DNA tests, fingerprinting, ubiquitous CCTV, constant surveillance of online activities and communications and in-person surveillance by more than a million party cadres. This particular manifestation of state power is unique in the world, and I do think it’s especially chilling, but I nevertheless view it as existing on a continuum with many others.

Protest in Washington D.C against Xinjiang’s Concentration Camps. Photo Credit: Wikipedia

Protest in Washington D.C against Xinjiang’s Concentration Camps. Photo Credit: Wikipedia

On the subject of objectivity, I’m going to be unhelpful again. I think publications that brand themselves as journalistic owe it to their readers to allow subjects, even oppressive state authorities, to respond to allegations of crimes and atrocities. When I published my oral history in The Believer, we wrote to various official Chinese government departments to give them the opportunity to respond. Had they responded, we would have included it. We did the same with my story for The New York Times Magazine. So I don’t believe in abandoning this kind of even treatment, even at the expense of a tidy narrative.

More generally, you owe it to your readers to present as complete a picture of a situation as possible, and that means not simply parroting disinformation or state propaganda, and it also means looking high and low for quality information and evidence. I did that. I didn’t talk to a single person from Xinjiang who refuted the essence of what others said about the oppression taking place there. (Of course details do often differ, as you can see in my work—I don’t gloss over it.) I cast as wide a net as possible looking for interviewees, and have given as broad a portrait of life in Xinjiang as I was able, not just about the state but about poverty, illness, marriage, childrearing. I consider this my attempt to present a many-sided reality. Isn’t that an approximation of objectivity? Not one side or two sides, but as many sides as you can bring into focus.

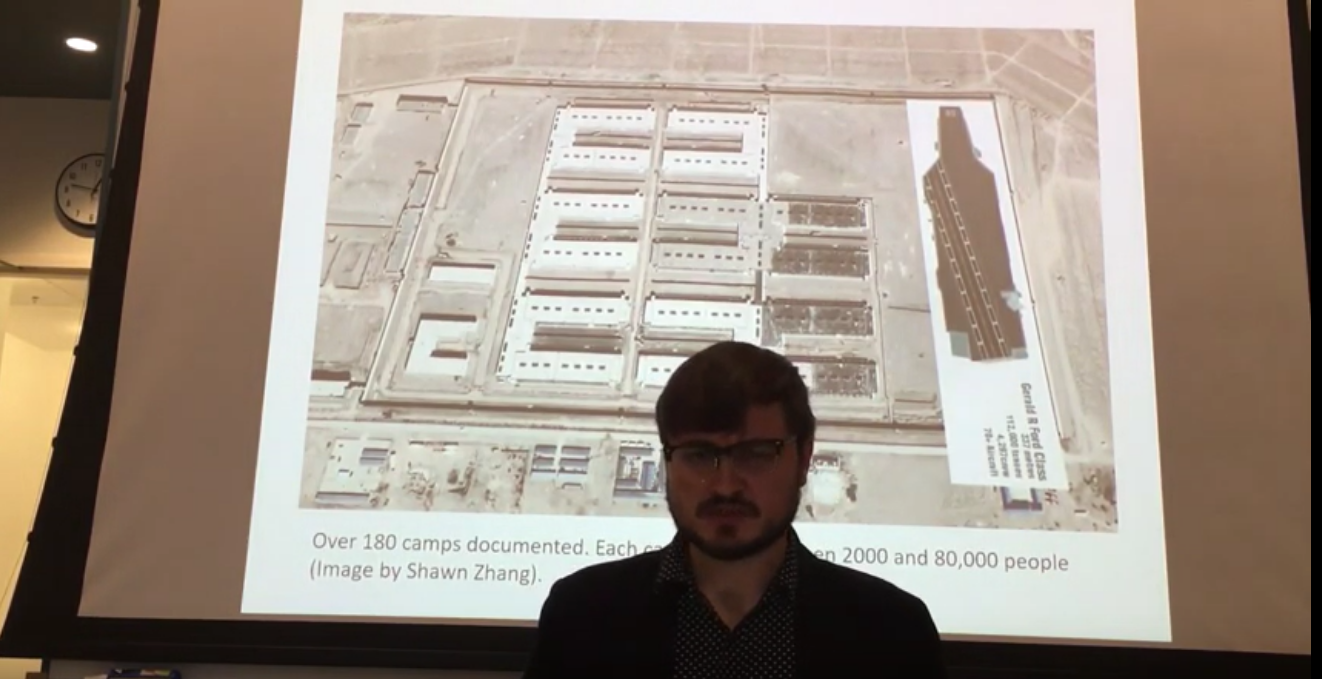

Darren Byler Lecturing on Xinjiang’s Concentration Camps. Photo Credit: The Art of Life in Chinese Central Asia

Darren Byler Lecturing on Xinjiang’s Concentration Camps. Photo Credit: The Art of Life in Chinese Central Asia

AAT: Do you see a companion piece to Weather Reports as important? A piece of writing that tries to identify, center and discuss the ‘ordinary’ men and women who tore down the mosques and built up these camps, guarded them or programmed the biometric systems or those who even in their silence helped implement this genocide that was dreamed up by China’s capital and state?

And how did the interview subjects of ‘Weather Reports’ speak about these minor figures culpability for Xinjiang’s Genocide, in comparison to major figures of a Xi Jinping or Zhang Chuxian? How did they speak about those who did not torture or jail them, but simply stayed silent when they were hauled away?

BM: There’s a good article by Darren Byler about some of the live-in cadres who are assigned to join Uyghur and other minority families in Xinjiang. That piece offers their own defense about the work they have been sent to Xinjiang to do. I found it very illuminating.

The people I interviewed, even those who were themselves detained, were surprisingly understanding about the life of guards and police officers. In some cases they knew these people from childhood, had grown up with them. This understanding even extended to live-in cadres, the “brothers” and “sisters” who lived in minority homes to correct their behavior, most of whom were Han. In my interviews, people understood that, for the most part, they had no choice. They were following orders like everyone else. There was surprisingly little resentment about their personal cadres, although they didn’t like or trust them, and they had heard scary stories of “bad” ones, too. It’s a system practically designed for abuse.

Of course, the main restriction on a story about the low-level grunt workers who have constructed the securitized police state in Xinjiang is that they are not free to talk to me. As with ethnic and religious minorities in Xinjiang, even approaching one for an interview puts their safety and their families at risk of reprisal from the state. They could go to jail. Unlike some reporters who use hidden cameras and things like that, I do not view myself as a proper judge of the value of information. I can’t ask “is this story worth the risk” when the risk is the safety or freedom of another person. I view my own work on Xinjiang as a collaboration with my subjects, and we discuss the risks, and their position as the story’s subject, at length. This isn’t possible to do right now in China, and even if it were, I don’t consider myself the person to do it.

Tacheng City Rural Home for the Aged (塔城市农村敬老院) This retirement home, also listed as the Tacheng City Community Welfare Institution (塔城市社会福利院), was converted into a camp sometime in 2017. . . A number of Kazakhstan citizens have been detained here, making this one of the better documented camps from an eyewitness perspective. Source: Xinjiang Victims Database

AAT: Another organization that along with Atajurt has shown incredible courage is the Xinjiang Victims Database, which like Atajurt (and correct me if I’m wrong) is an all-volunteer effort run by ordinary people with no powerful connections. I spoke to their founder Gene Bunin who said to me in our interview:

“In general, I wouldn’t really advise anyone to rely on governments to solve these issues on their own. There needs to be a ton of grassroots and similar pressure.”

Something in the context of Xinjiang that stumps me (but this applies to global protests) is this idea of ‘protesting against governments we all know are illegitimate. Can you tell me why, in the face of authoritarianism, Atajurt (or XVD) had success to begin with?

BM: Gene has been an important figure in collecting information and testimony from Xinjiang. I don’t think it’s all-volunteer, actually, I think he is able to pay his team of translators, and I know he himself lives very monastically in order to focus his resources on the database. He manages to do it completely independently through small donations, which is all the more impressive. He is also very patient with journalists like me, so I really appreciate him and his work. I think we also agree on the futility of seeking a solution through geopolitics, through the interaction of states and empires. In my opinion, grassroots pressure and creative thinking, especially among an anti-war, anti-imperialist left, while listening to and working alongside Uyghurs, Kazakhs, and other oppressed peoples of Xinjiang, as well as critical voices from elsewhere within China, will be the solution to this crisis.

I wrote about Atajurt’s early success for the London Review of Books, so my answer would be similar to what I wrote there. They were a very small volunteer operation, surprised by their own success, suddenly in the public eye and very quickly affected by suppressive efforts, attacks by the secret police, arrests, fines, etc. They are now effectively defunct, and those trying to revive the work are facing new fines and legal challenges from the government of Kazakhstan.

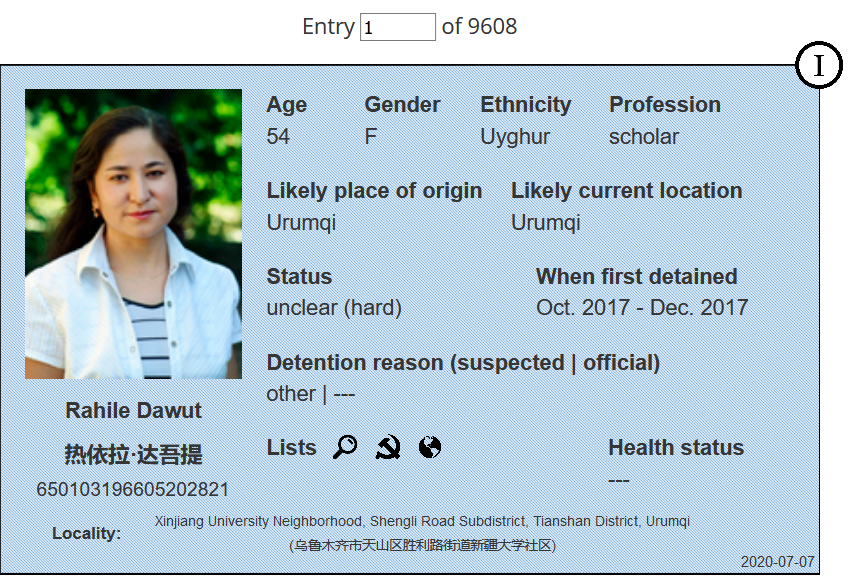

Gene Bunin’s Xinjiang Victims Database, is one of the most comprehensive datasets of the victims of China’s campaign of mass imprisonment. Read our interview w. Gene Bunin here.

Gene Bunin’s Xinjiang Victims Database, is one of the most comprehensive datasets of the victims of China’s campaign of mass imprisonment. Read our interview w. Gene Bunin here.

AAT: I have not cited heavily from Weather Reports as I think everyone should read the essay in full, but one testimony in particular had me gasping and crying out loud:

“The local police liked to say that they were watching us through their satellite system. We know what you’re up to in your kitchens, they said. We know everything. We had a friend at the time. A police officer told him that special equipment was installed that allowed them to see right through walls into a house, and that nothing could be concealed. Who knows what’s true anymore? So we were burning everything at night—Korans, prayer rugs, traditional clothing. We burned them at night because we were afraid the satellites could see us during the day.” — Shakhidyam Memanova, 31

Scenes like this connect to me with the work of Ralphael Lemkin and Peter Balakian describing the horrific cultural aspects of the Armenian Genocide, how one of the main goals was to completely erase the culture of the Armenians. From talking to victims in Xinjiang, what aspects of cultural genocide are being put into place along with physical genocide?

BM: I think this testimony, like the whole collection, speaks for itself better than I could, and like I said my goal with these oral histories is to center the firsthand testimonies of people from Xinjiang, and not to center my own interpretations of their stories. These are Shakhidyam’s words, about which I deliberately say as little as possible. And I chose it as the final testimony for a reason. It’s the story I most hope the reader takes away with them.

Another point: I don’t use the term “genocide” here or elsewhere in my work on Xinjiang. Whether or not it applies to what is happening in Xinjiang, it’s a legal term, one that may be useful in the world of international law, but it is useless in work like mine, just as “first-degree murder” is not helpful if your goal is to tell the story of the victim of a stabbing. (If you’re telling the story of the killer’s trial, that’s another story.) The urge to find superlatives and to use terms like “genocide” are part of a desire for categorization and judgment that I understand as a person but reject as a writer: it allows the reader to close her eyes to the particulars of these stories, to view the tragedy en masse, as a collective of suffering. This is something that Westerners are too often keen to do rather than attend to the specific nature of sorrows and troubles of other people, the individual distinctions of atrocities across the non-Western world in which we may find ourselves implicated. You should read Shakhidyam’s story because it is tragic and sensitively rendered; because it is believable and in all likelihood true; and because it is hers alone; not because it is evidence of any kind of genocide, including cultural genocide, whatever that is.

AAT: For those you interviewed, something that haunted me was the question of their stories after you left them. From what they told you and your own follow up work, Can they go back to the ‘normal world’ after having personally experienced genocide? Does anyone (Armenians, Jews, Palestinians, West Papuans, Indigenous Americans) ever go back to ‘normal’? How can one go back to a ‘normal’ when genocide emerged from that very normal to begin with?

BM:There have been some happy cases—families reunited, usually following a loud and persistent public outcry about an individual’s detention over several months. But often it is a state of perpetual unease. Most of the subjects of my oral history described mental and physical trauma that tormented them, and their desire to get medical care—not just physical treatment but therapy. As with many other historical traumas, it is undoubtedly producing trauma that will echo across generations. Most of the people I speak with are living in Kazakstan and see no future for themselves or their families in Xinjiang. If they have relatives in Xinjiang, as most do, they believe they will never see them again. I don’t think there’s any hope of emerging unscathed from this kind of trauma.

Video of the forced patriotism of Uyghur detainees that was widely circulated among Uyghur diaspora in February 2018. Source: The Art of Life in Chinese Central Asia

AAT: To conclude, Long T. Bui, Achille Mebembe and Jodi Melamed are some of the most helpful thinkers on the centers of knowledge (Universities/Corporations) that train the administrators and technicians of necropolitical systems. Through your interviews, and thinking through modern statecraft, did you have a sense of what global contributions or carceral techniques came together to form the ‘Xinjiang System’? And if Xinjiang was built with global knowledge, can we shut off (in our own countries) the knowledge-training and perfecting of surveillance that made Xinjiang’s systems of incarceration possible?

BM: As many other scholars have observed, the rhetoric and tactical approaches of the US War on Terror have been foundational to the security state in Xinjiang, from the vocabulary of anti-terrorism to the explicit strategies of detainment, interrogation, and brainwashing of a recalcitrant population. David Brophy and Darren Byler have written about Xinjiang’s transformation, in the eyes of the state, into a counterinsurgency war zone, along the lines of what happened during the US invasion of Iraq and Afghanistan. All these cases birthed zones of exception where militants must be ferreted out from among a suspect civilian population. These zones always exist outside a state’s normal rule of law, such that civilians there may be treated prima facie as fugitives; at the same time, the state reserves the right to conjure such zones into existence whenever and wherever it likes. When a state’s power goes unchecked, anyone may become a fugitive at any time, for any reason. We have seen just that happen in Xinjiang, where my informants were detained because they had a common app on their phone or prayed at a mosque, or performed religious ceremonies.

Byler in particular has written about the importance of the book Policing Terrorism by David Lowe to the development of securitization policy in Xinjiang. Its descriptions of radicalization processes and the importance of surveillance lit a fire under some of the architects of the crackdown in Xinjiang, who saw its applicability to the “pre-emptive strike” mode employed in Xinjiang, where various forms of wrongthink are cause for indefinite detention or disappearance under the assumption that they will lead to the “three evils” of separatism, extremism, and terrorism. One interesting departure, which he notes, and which is an important feature of the stories I’ve gathered from people from Xinjiang, is the importance of local police stations, where judgment calls are made about the freedom or detention of an individual, and the in-person surveillance of the Becoming Family program, which represent a total eradication of private life. Turkic and Muslim minorities in Xinjiang have no right to a private sphere or a life outside the view of the state, and even those employed in the surveillance are themselves under scrutiny.

The China – Kazakhstan Border. Photo Credit: Wikipedia

The China – Kazakhstan Border. Photo Credit: Wikipedia

Another component in the Xinjiang System has been what David Tobin describes as the attempted construction of a shared multi-ethnic identity. This effort was redoubled after the Ürümchi riots in 2009, when it became a “zero-sum political struggle of life or death” according to government officials. I think this process of identity formation, the creation of a national identity out of disparate ethnic groups and historical conditions is common to modern statecraft, and the apocalyptic tone it often takes—nation or barbarism—allows for the criminalization of nearly anything viewed as standing in its way.

In Xinjiang, however, there has been a marriage of preventative policing and the transformation (or eradication) of a culture by the state, which is why authorities view as so important Chinese language instruction and the suppression of Uyghur and Kazakh language use, as well as the criminalization of fasting and prayer, religious study, and other “dangerous“ cultural practices that mark a population as separate. In their place, anodyne cultural markers like dress and dance are overemphasized to create the impression of tolerance and diversity. But in reality, the anti-terrorism techniques of Policing Terrorism and its ilk have been wedded to a policy seeking “deep fusion” between Turkic minority culture and the ethnic Han majority. This effort, to correct the “personality problem” at the heart of Xinjiang’s unrest, is the “most distinctive aspect of the Xinjiang Mode,” according to a paper by two theorists that came out of a Xinjiang police academy, which has been analyzed by Byler. As a result, you see the conflation of vernacular resistance with organized, armed separatism, and the emergent fugitivity or fugitivization of identifiable minorities, artists, and intellectuals, which has become the focus of my reporting and writing.

Qaraqash No. 2 Training Center (墨玉县第二培训中心): A former warehouse logistics yard turned into a camp and possible labor site, Qaraqash’s No. 2 training center is located just northeast of the county’s main train station (墨玉站). (The photo above, sourced from http://archive.is/yst4x, is not of the camp facility but of young locals being sent to other parts of Xinjiang for work – the old logistics yard, not visible here, is 200-300 meters behind them, following the camera angle.) Source: Xinjiang Victims Database

Qaraqash No. 2 Training Center (墨玉县第二培训中心): A former warehouse logistics yard turned into a camp and possible labor site, Qaraqash’s No. 2 training center is located just northeast of the county’s main train station (墨玉站). (The photo above, sourced from http://archive.is/yst4x, is not of the camp facility but of young locals being sent to other parts of Xinjiang for work – the old logistics yard, not visible here, is 200-300 meters behind them, following the camera angle.) Source: Xinjiang Victims Database

For more of Ben’s outstanding journalism, please visit: Ben-Mauk.com